From Marine Corps orphans to top-scoring fighter squadron, VMF-214 followed their brawling leader, “Pappy” Boyington, to fame

|

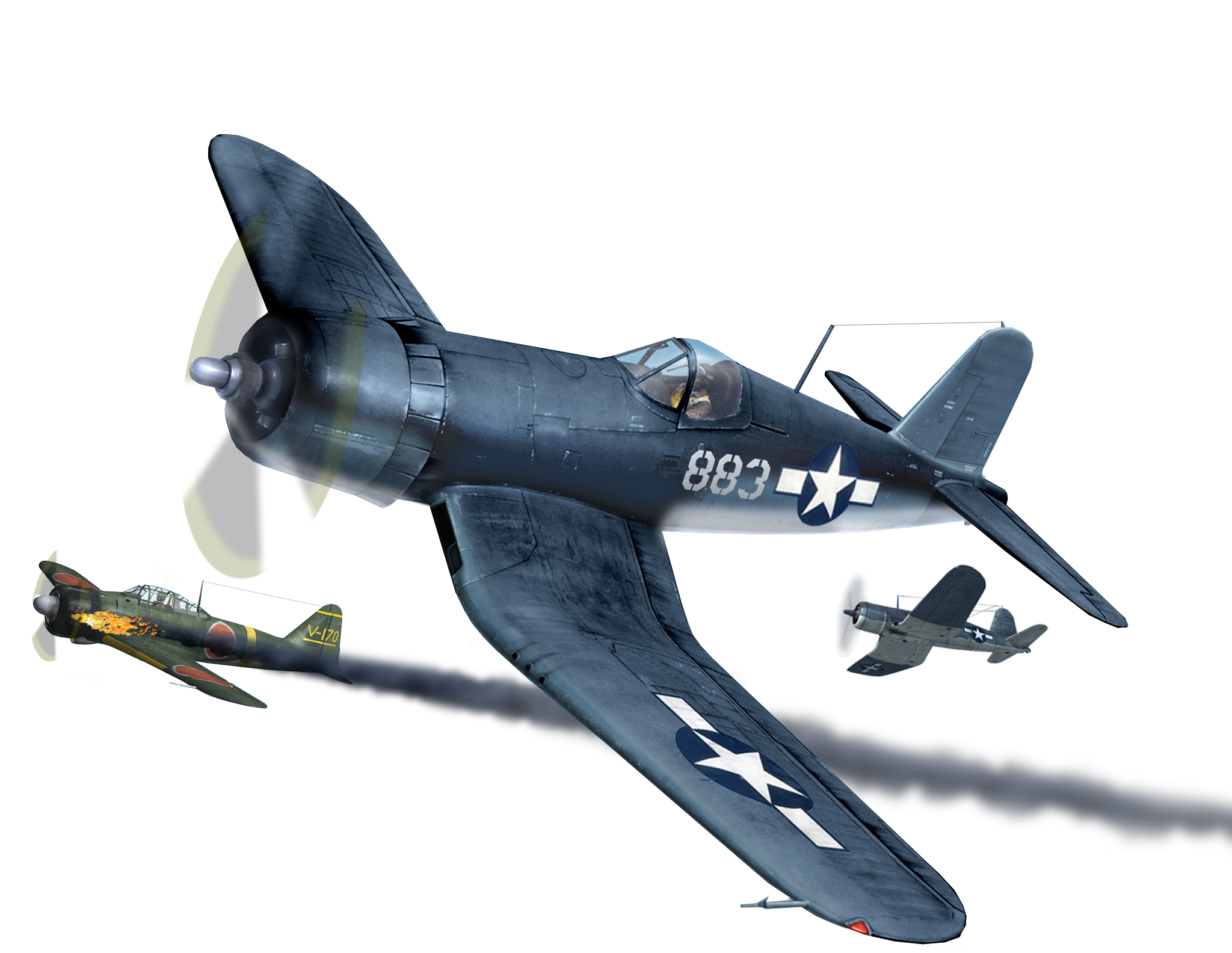

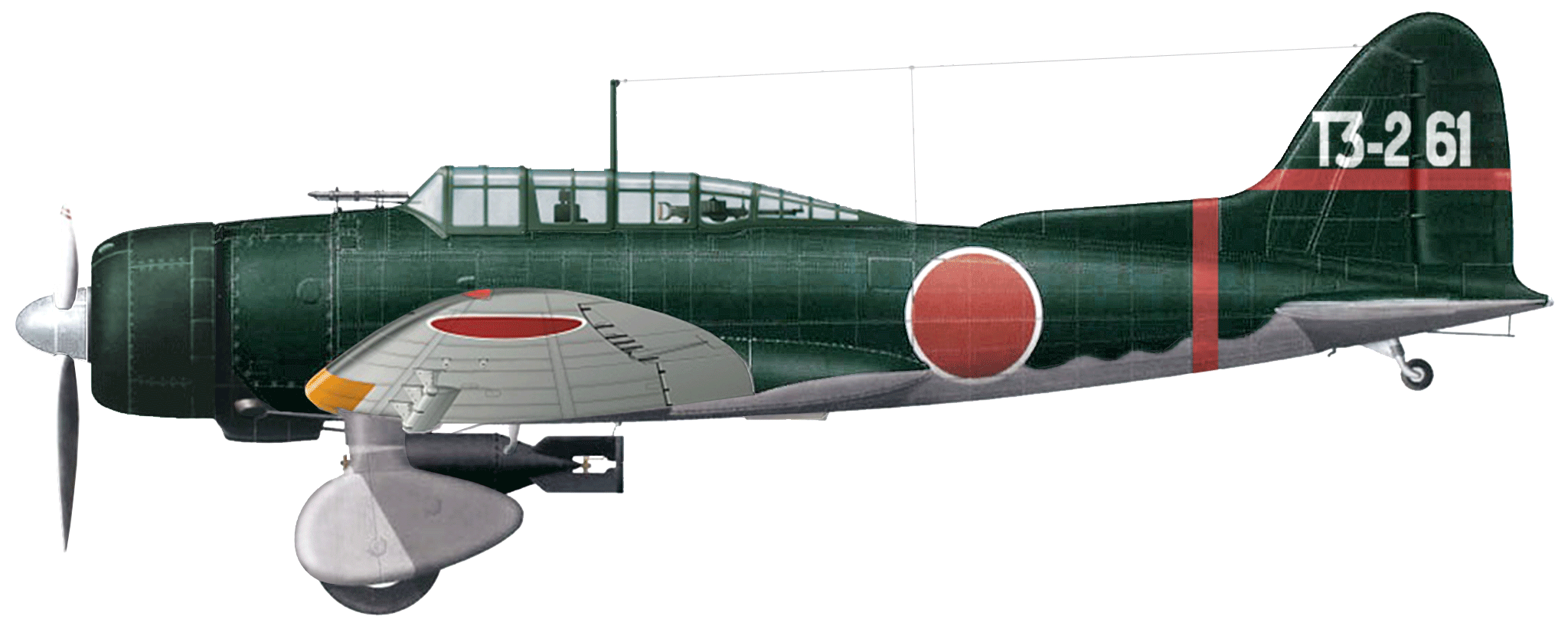

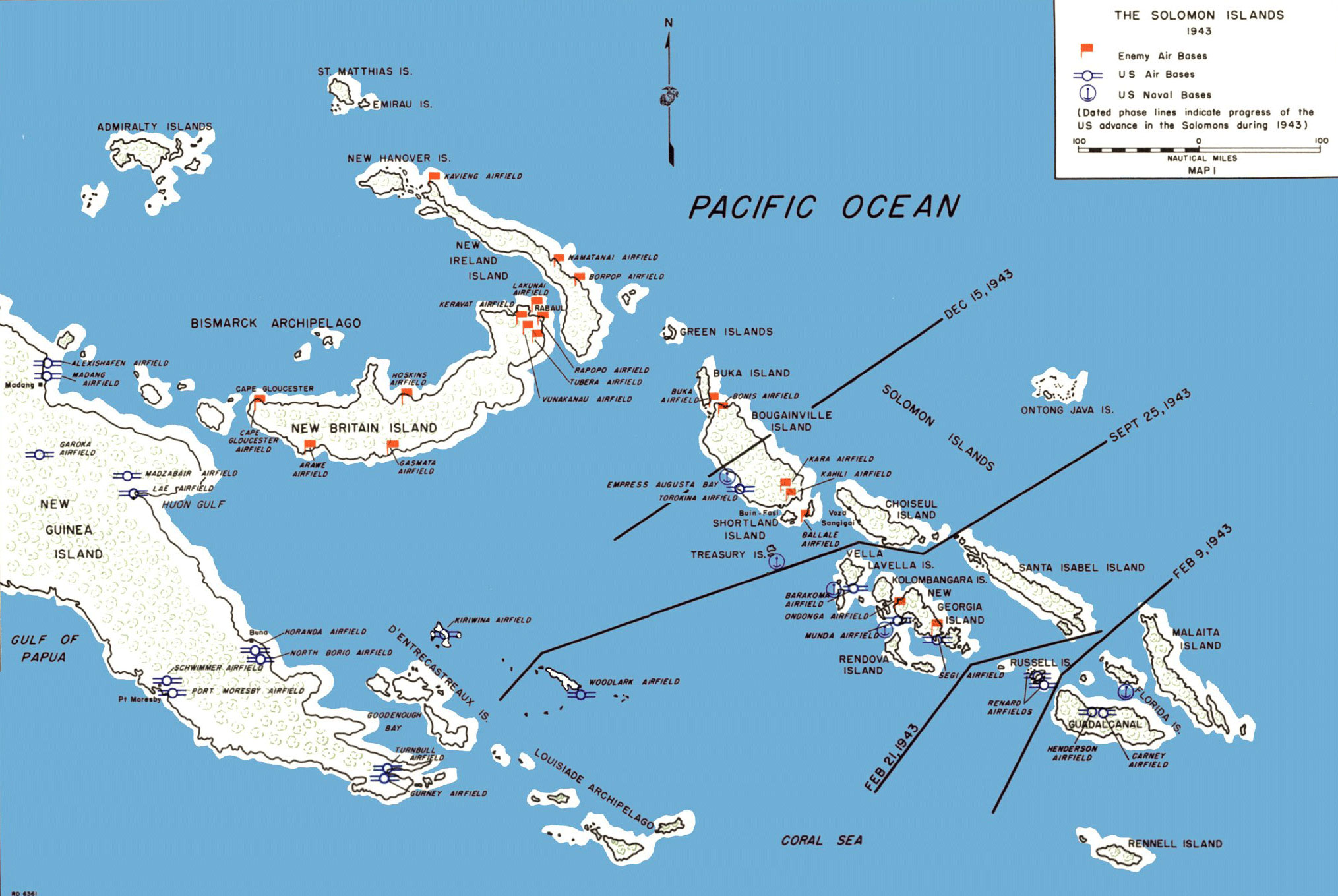

F4U-1 Corsairs of Marine Fighter Squadron VMF-214, late 1943. “Pacific Morning: Black Sheep on the Prowl” by Craig Kodera. It was one of the biggest air raids in the entire campaign for the Solomon Islands. More than a year after U.S. Marines landed on Guadalcanal, Navy TBF Avengers and SBD Dauntless dive-bombers were to hit the Japanese base on Ballale, at the far end of the island chain, on September 16, 1943. Navy F6F-3 Hellcats and Royal New Zealand Air Force P-40 Kittyhawks flew cover. And way up over 20,000 feet—either for altitude advantage or their own protection—were some two dozen Marines. VMF-214 was a newly reorganized squadron on just its third mission, and flying an ill-starred fighter to boot: the Vought F4U-1 Corsair, or “Bent-Wing Bird.” High atop the four-mile-tall array, squadron commander Major Gregory Boyington was feeling sorry for himself. Without victories, his cobbled-together squadron of shiny new lieutenants and disbanded-unit orphans would soon be washed back into the replacement pool. He almost didn’t notice when the rest of the massive American formation suddenly dived under a layer of stratus. “What in hell goes?” he muttered. “We must be over the mission.” Following him down, the other Corsair pilots found the bombers pounding Ballale and dozens of Japanese fighters coming up to do battle. Boyington was suddenly amazed to find, not 30 feet away, a red-balled A6M Zero practically flying on his wing…and that he had completely forgotten to switch on his gunsight and guns.

Commissioned in July 1942, Marine Fighter Squadron (VMF) 214 were originally called the “Swashbucklers.” They flew out of Henderson Field, Guadalcanal, during the early Solomons campaign, but were disbanded thereafter and the squadron number reassigned. Most Americans think of “Pappy” Boyington as actor Robert Conrad portrayed him in the TV series Baa Baa Black Sheep, yet even that nickname was invented by the press. In the Solomons his pilots called the 30-year-old major “Gramps.” He had claimed six victories in China, flying P-40s for the American Volunteer Group (though the Flying Tigers only credited him with two) and arrived in the Solomons just as the Marines replaced their old Grumman F4F-4 Wildcats with new Corsairs.

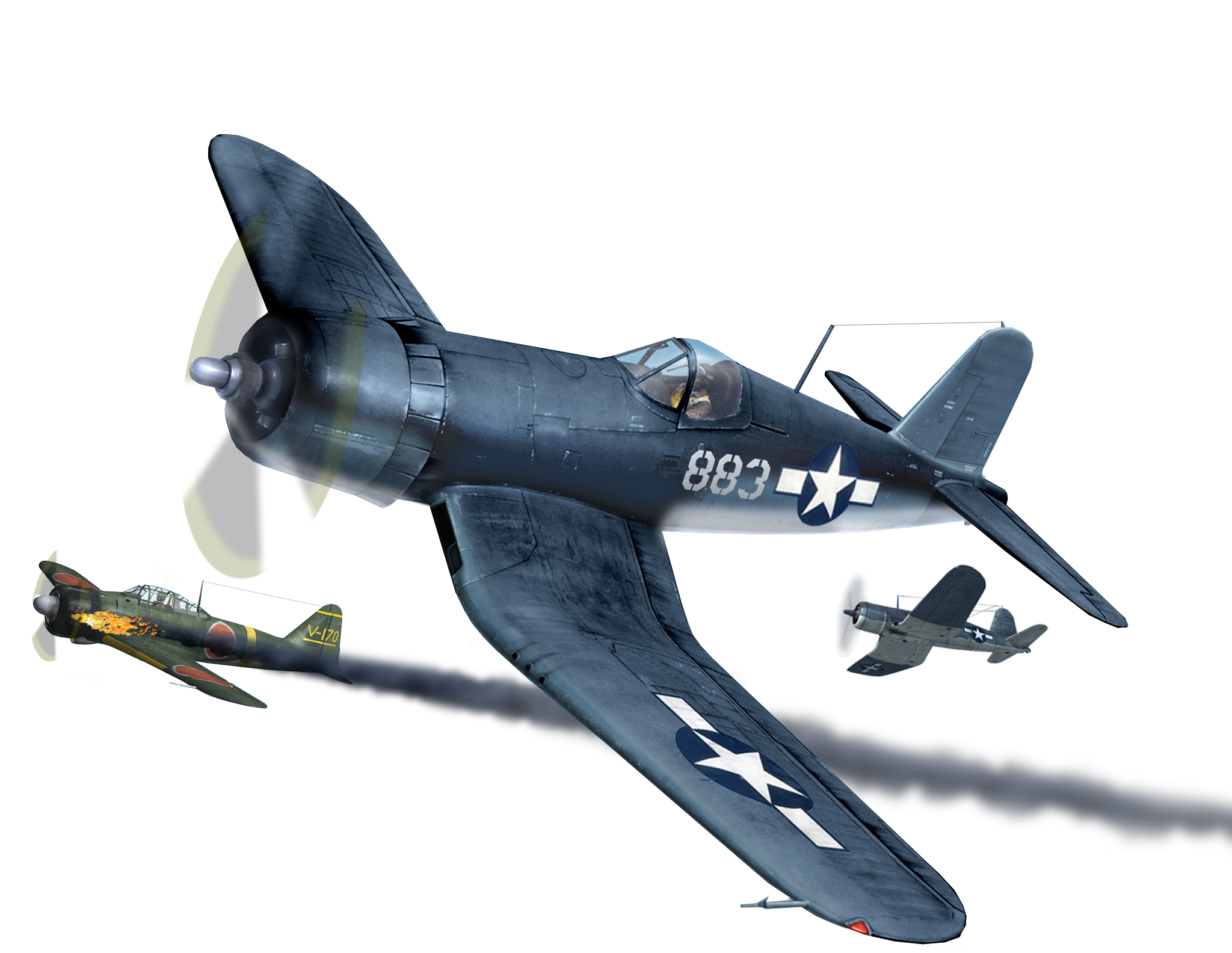

An F4U touches down hot at Espiritu Santo. The Corsair’s high landing speed and unforgiving stall characteristics forced pilots into tail-high approaches to see over its 14-foot nose, causing the US Navy to ban it from carrier ops until Royal Navy pilots demonstrated a curving approach that let pilots see around, rather than over, the cowling. Designed behind a bomber-size prop more than 13 feet across (the inverted gull wings and long nose were necessary to give it ground clearance), the F4U was the first American single-engine plane to average more than 400 mph, but it was prone to unrecoverable spins and landing stalls, and that “hose nose” blocked the pilot’s vision on straight-in carrier approaches. The Navy judged it unfit for shipboard ops, but good enough for the Marines. In Boyington’s opinion: “The Corsair was a sweet-flying baby if I ever flew one. No longer would we have to fight the Nips’ fight, for we could make our own rules.” He made his own squadron, too. Later portrayed on TV as misfits and rejects awaiting courts-martial, the “Black Sheep” (the first choice, “Boyington’s Bastards,” was nixed: not press-friendly) were in fact among the most experienced pilots in the Pacific theater. Even the rookies had accumulated high flight hours, and several of the veterans counted more victories than Boyington. Though they had flown together only briefly before September 16, the results of that first day of combat were unequivocal.

In a famous photo, members of the newly re-formed VMF-214 “scramble” for an intercept. Except the photo was staged on Espiritu Santo, hundreds of miles from the Solomons, and taken September 11, 1943, before the Black Sheep had flown together in combat. Pilot at left, with Australian flight boots, is Bill Case.

Lt. Bob McClurg

Lt. Don Fisher At the post-mission debrief Lt. Bob McClurg reported getting his first kill in a head-on pass: “I just held the trigger down as we came at each other. I was scared to death.” Boyington’s wingman, Lt. Don Fisher, scored two, including one that he shot off his leader’s tail. “I was right behind [the Zero], and he blew,” Fisher recounted. “The wings went each way.” But he had lost sight of Gramps, who was hours overdue returning to base. VMF-214 had almost marked Boyington MIA when his Corsair at last arrived and he climbed out of the cockpit, claiming no fewer than five enemy kills—even discounting his AVG victories, an ace in a day. After maneuvering the first Zero into an overshoot (and charging his guns), Boyington reported sending it down in flames and gunning down enemy fighters halfway back home, including one that “exploded completely when I was about 50 feet from him.” Too close to evade, he had flown directly through the explosion, somehow dodging the pilot, engine and still-spinning prop.

Boyington flies through his target’s explosion. “Corsair F-4u1” by Julien Lepelletier There was no gun camera film in those days; Boyington had only his word to back up his claims. But he had stopped off at the recently captured forward air base at Munda, on New Georgia, almost out of gas and ammo, with dents all over his Corsair from flying debris. His kills—almost half the squadron score of 11, plus eight probables—were confirmed. Within a few weeks, propelled by the CO’s Flying Tiger backstory and the Marine Corps press machine, the Black Sheep were a household name. And they were just getting started.

Lt. John Bolt

Lt. Bill Case Lieutenant Bill Case had only scored a probable over Ballale. One week later he held his fire to within 50 feet of a Zero’s tail—too close—and his Corsair’s six wide-set wing guns straddled its fuselage. “I spent about 2,000 rounds figuring that out,” said Case. “I finally put the pipper up above his tail and about six to eight feet to the side…and hit him with three guns at a time.” Lieutenant John Bolt had missed his first kill over Ballale. “The first time I saw a meatball it was a full deflection shot, and he just zipped by,” he reported. “I was in a state of shock.” Over Vella Lavella, however, Bolt got behind two Zeros in succession, flaming both for a double kill.

F4U-1 Corsair

Lt. Chris Magee

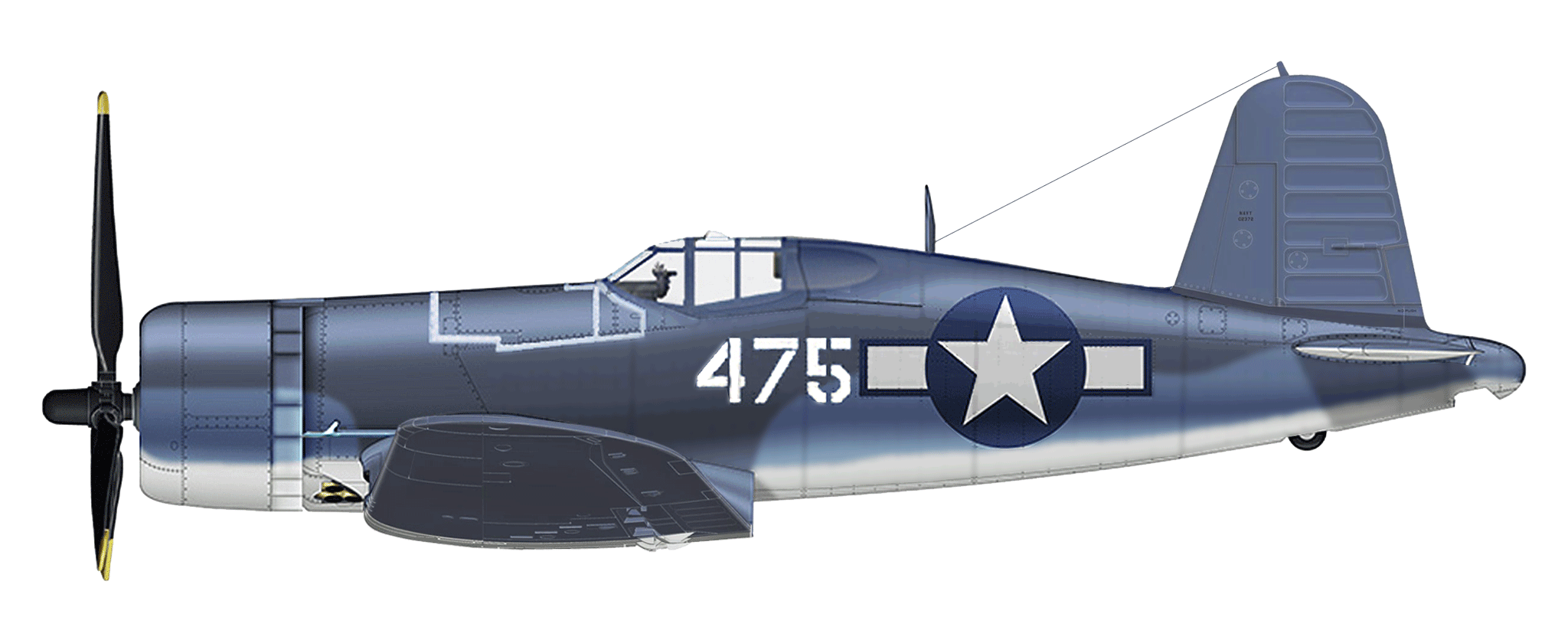

Aichi D3A1 “Val” of 582nd Kokotai, Munda, New Georgia, 1943 Despite being obsolete when the war started, the Val was the primary Japanese dive bomber throughout the war. So agile it was sometimes flown as a fighter, it also served as an interceptor and kamikaze plane. It sank more Allied warships than any other Axis aircraft. Lieutenant Chris Magee had likewise been flummoxed by the speed of air combat: “All I could do was keep spinning my neck and looking…everything was happening so fast.” Called “Maggie” (though rarely to his face, as he was a dedicated weightlifter and fitness fanatic), Magee plunged from 13,000 feet into a pack of Aichi D3A2 “Val” dive-bombers attacking a U.S. convoy. “The Japanese were going into a straight dive, so I headed into the dive with them,” he recalled. “Of course, by then the [American] anti-aircraft was all around us, but you don’t even think of that….The [Vals] kept going down, and I kept in there, firing.” By the time they pulled out above the water, he had splashed two, and a third probable, when he heard bullets striking his plane “like a hail storm on a tin roof.” The Vals’ escort—Zeros, always slow in a dive—had caught up. Magee made it back to base with 30 bullet holes in his Corsair. He was recommended for a Navy Cross, and his nickname changed to “Wild Man.”

“Magees’s Cross” by Darby Perrin

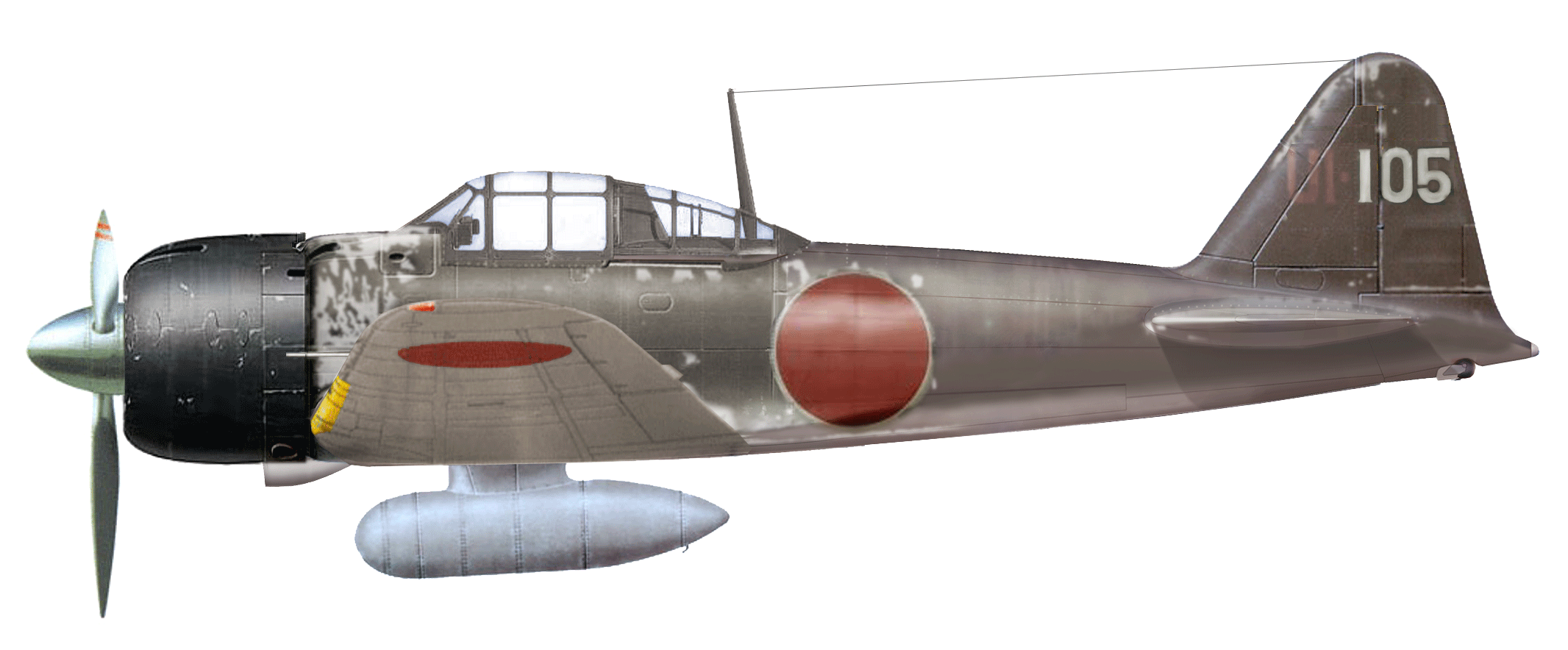

Mitsubishi A6M3 Model 22 “Zeke” The Model 32 had no folding wingtips, less range and less maneuverability than the preceding Model 21. The Model 22 corrected these deficiencies, but was still not the equal of the Corsair. Production ended in mid-1943, but the Model 22 was often encountered by the Black Sheep over the Solomons. Model 22 UI-105 was flown by Lt.j.g. Hiroyoshi Nishizawa, the “Demon of Rabaul.” During the late 1943 island-hopping campaign up the Solomons, VMF-214 flew out of bases so far forward that they were often behind Japanese lines. (Navy Seabees had started the reconstruction of desolate, bomb-pocked Munda while the enemy still held the far end of the strip.)

After the months-long ordeal on Guadalcanal, the Allied island-hopping advance up the Solomons toward Rabaul on New Britain was complete by the end of 1943. Torokina on Bougainville was within fighter range of Rabaul, allowing the “Pearl Harbor of the South Pacific” to be hammered to inconsequence. On their first tour, the Black Sheep suffered an almost 40 percent casualty rate, including one pilot shot down in a friendly-fire duel with Navy PT-boats. Yet they overflew Bougainville so regularly that the Japanese dared Boyington by name to come down and brave the anti-aircraft; instead he taunted Zero pilots that they should come up and fight. John Bolt even flew an unauthorized one-man air raid on Tonolei Harbor, making two strafing runs on troop transports and boat traffic. “I was only taken under fire from one gun,” he reported to a furious Boyington on his return, adding that its 20mm tracers “just floated by.” Despite his CO’s ire, Bolt received a congratulatory telegram from no less than Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, and the Distinguished Flying Cross. He would eventually earn a Navy Cross as well.

“Black Sheep Squadron” by John D. Shaw

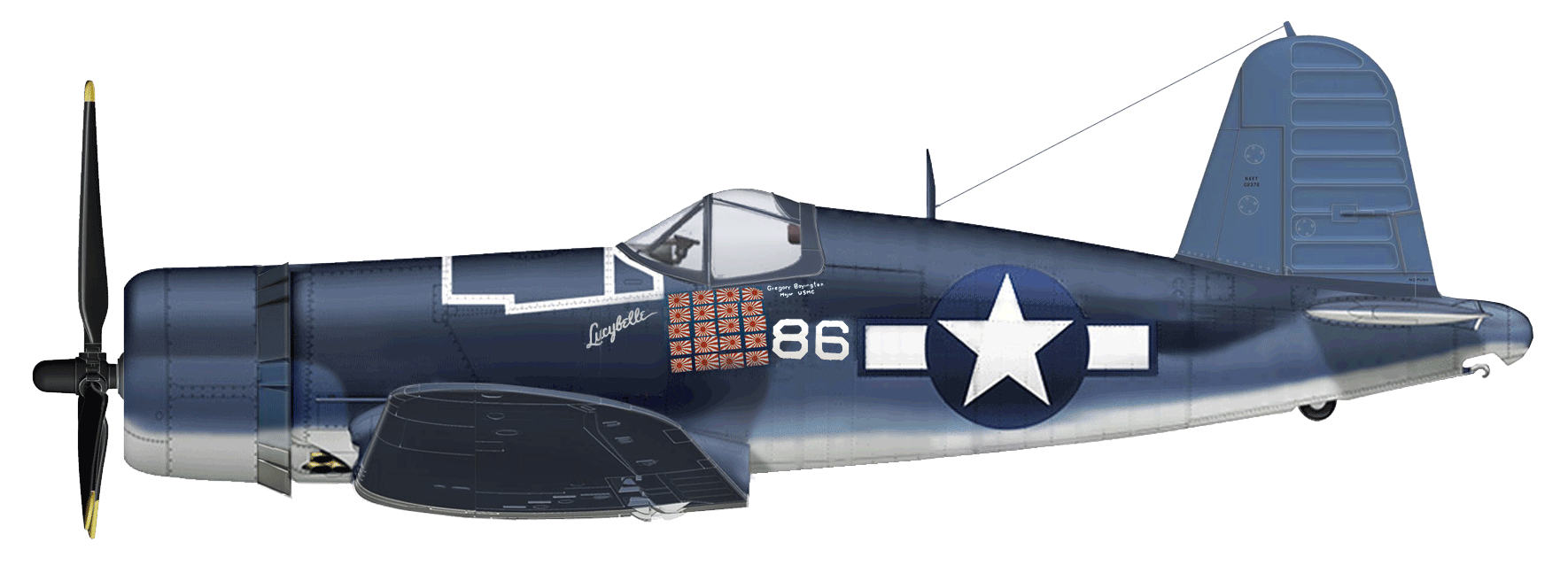

The Black Sheep pose on the wings of Corsair #17740 in its revetment at Vella Lavella, Dec. 27th, 1943. The St. Louis Browns had issued them one team cap for each victory. Aces hold baseball bats. In six weeks VMF-214 scored 57 kills, with 19 probables. Wild Man Magee claimed seven. Bill Case finished with eight. (On his last mission, for no real reason Case lowered his cockpit seat a notch; when a Japanese 7.7mm bullet pierced his canopy, instead of drilling him through the skull, it merely creased his scalp.) Halsey visited VMF-214’s base to shake hands all around. Boyington was nominated for the Medal of Honor. At a November photo op on Espiritu Santo, a Corsair was dressed up with his name and 20 Japanese victory flags, though in fact it was a point of pride in the squadron that they all shared airplanes; not even Boyington flew a personal mount.

F4U-1 Corsair “Lucybelle”

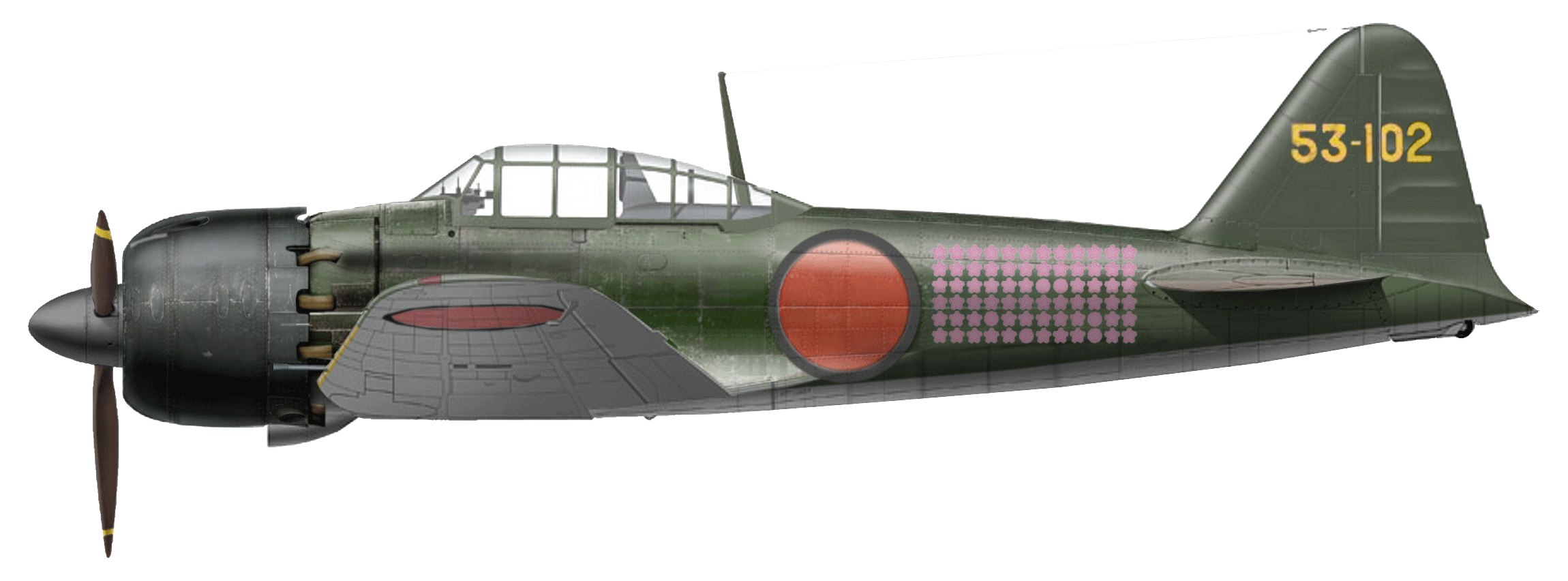

Mitsubishi A6M5 Model 52 “Zeke” The most-produced of the A6M series, the A6M5 entered service in October 1943. With a more powerful engine, wingtips “clipped” for better roll rate, and dive speed increased to 410 mph, the Model 52 was intended to be a match for the Corsair and F6F Hellcat. In late 1943 53-102 was flown out of Rabaul by Lt.j.g. “Tiger” T�e�t�s�u�z�o �I�w�am�o�t�o�, who survived the war as possibly Japan’s highest-scoring ace. Hero-hungry America couldn’t get enough of the Black Sheep. Neither could the Marine Corps, which boosted squadron pilot strength from 28 to 40. On November 1, 1943, the Allies finally landed on Bougainville, capturing just enough beachhead for a staging field at Torokina. For the first time Allied fighters could reach Rabaul, the “Pearl Harbor of the Southwest Pacific.” Within shooting distance of 26 victories—the American record held since World War I by Eddie Rickenbacker, only recently tied by Captain Joe Foss—Boyington led a fighter sweep, marking the first appearance by American single-engine planes over Simpson Harbor. (When a Navy squadron commander questioned his tactics, Boyington snapped: “Tactics? Hell, you don’t need any tactics. When you see the Zeros, you just shoot ’em down, that’s all.”)

Lakunai

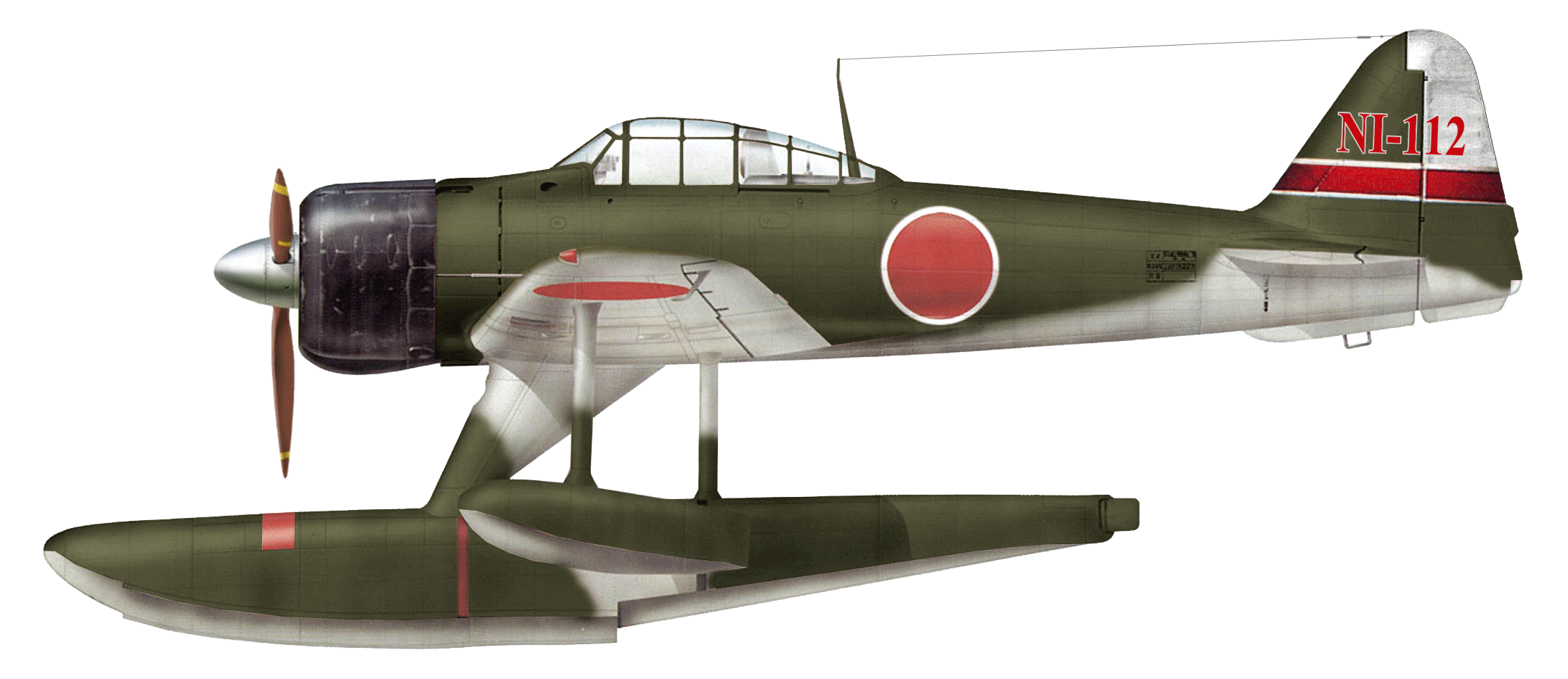

Nakajima A6M2-N “Rufe,” 802nd Kokutai, Solomon Islands 1943 A seaplane version of the Zero, the Rufe saw action in the Aleutians and Solomon Islands campaigns as an interceptor, fighter-bomber, and scout. Its performance suffered from the weight and drag of its large pontoons, making it easy prey for conventional Allied fighters. Against such an armada, however, the Americans found few Zeros willing to fly. McClurg broke formation to dive after a Nakajima A6M2-N “Rufe” floatplane, his fourth kill: “He was sitting there just flying straight and level. Nothing to it….[Boyington] looked over at me shaking his fist at me for breaking formation.” But the CO himself went down alone to strafe the air base at Lakunai. “We scared them,” he declared. “We ought to send up only about 24 planes, so they’d be sure to come up and fight.”

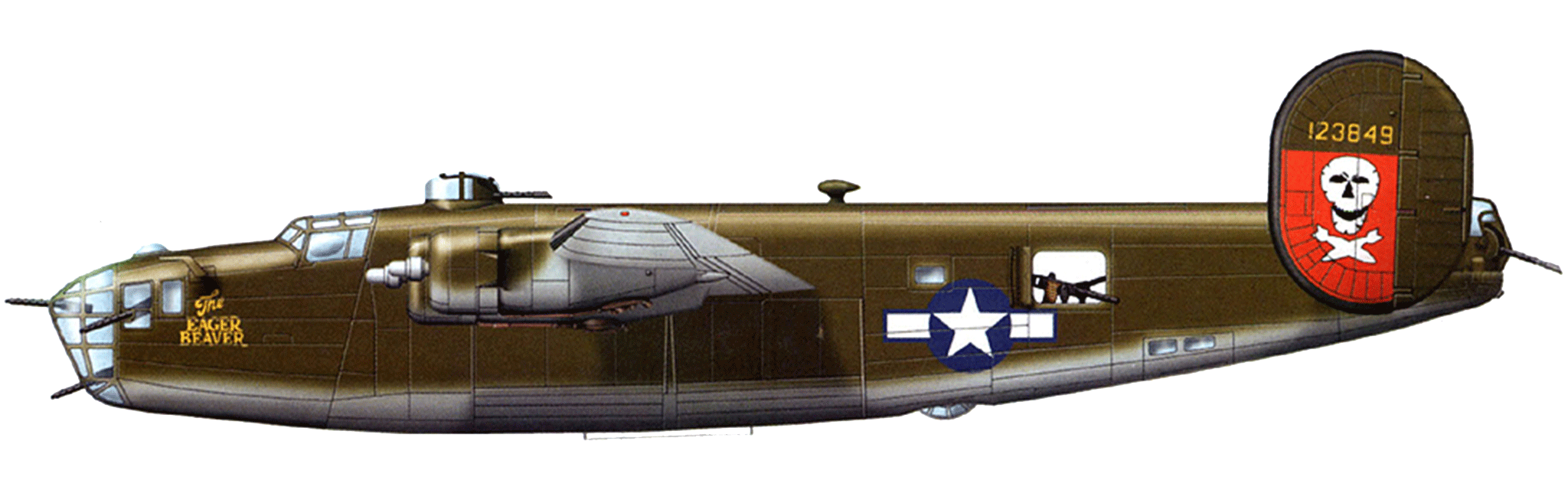

Consolidated B-24 Liberator Able to carry 8,000 lb of bombs, or 2,700lb for 3,000 miles, the B-24 was the prime Allied heavy bomber in the Pacific before the advent of the Boeing B-29. The Black Sheep escorted many of them to Rabaul. “Eager Beaver,” a B-24D-7-CO of the 320th BS, 90th BG USAAF, completed 77 missions in the Southwest Pacific theater. A week later the Allies sent two dozen B-24 Liberators, backed up by nearly 100 Corsairs, Hellcats, Kittyhawks and even Army P-38 Lightnings. This time the Japanese matched them fighter for fighter. In this titanic dogfight over Rabaul the Black Sheep lost three but claimed 12, Bolt and McClurg getting doubles to become aces, Magee raising his total to eight. And Boyington got four, at one point taking on a nine-plane formation all by himself: “I came down unknown to the Zekes and picked off the tail-end man, and then ran like a son-of-a-gun.” On the way home he even made a strafing run on a Japanese sub he caught on the surface. It was his second-best day ever as a Black Sheep.

“Fly for Your Life” by Robert Taylor.

With Rabaul visible in the distance, “Pappy” Boyington and his fellow pilots of VMF-214 tear into a large formation of Japanese Zero fighters. Buy the art.

The closer he came to the record, however, the more he seemed to feel the weight of history bearing down on him. He gave reporters wave-offs and brusque replies: “I didn’t come out here to make news. I came out here to fight a war.” McClurg got his eighth, Magee his ninth and Don Fisher got a double to become an ace, but Boyington stalled. “The hunting was fine,” he said of those last days of 1943, “…but I’m doing some dumb things up there!” He scored one more Zeke over Rabaul, but the next day was so outflown by an enemy fighter he reported it as a Nakajima Ki-44 “Tojo” that got away, scored only as a probable. On a subsequent mission he had to turn back with his windscreen covered in oil; at one point, as several fellow pilots attested, he undid his straps and stood up into the slipstream to wipe it off. “Don’t worry about me,” he told his men. “If you guys ever see me going down with 30 Zeros on my tail, don’t give me up. Hell, I’ll meet you in a San Diego bar and we’ll all have a drink for old times’ sake.” They celebrated New Year’s Eve Black Sheep style, firing off so many pistol flares that the transport fleet offshore got underway, fearing an air raid.

Gunfight Over Rabaul by Jack Fellows Boyington maneuvers for an advantageous position against a nimble A6M2 type “Zero” fighter over Rabaul on December 27, 1943. On this date Boyington shot down his 25th enemy aircraft, a Zero over Simpson Harbour.

Major Gregory “Pappy” Boyington, USMC, C.O. VMF-214 by Jack Fellows Another view of same dogfight, Boyington’s 25th confirmed aerial victory. Enemy aircraft was most likely a Zero from IJN 253rd Kokutai, coming up from Lakunai aerodrome. On January 3, 1944, Boyington led another sweep to Rabaul. The Japanese saw the Americans coming and sent up some 70 fighters to intercept. Boyington led the charge down into them. “I poured a long burst into the first enemy plane that approached,” he said. The Zero burst into flames, and several pilots witnessed it going down: Boyington’s record-tying 26th victory. But then they lost sight of Gramps in the low-level haze, where he found some 20 enemy fighters waiting. Word of his record kill preceded him back to base. “There was a radio recording hookup,” remembered one Black Sheep, “and the Marine Corps and Navy photo sections had cameramen there.” Elation turned to shock and disbelief when Boyington failed to return. “In the movies it would be labeled pure corn,” wrote one correspondent. “Things like that don’t happen.” Bolt got his sixth the next day, but adding insult to grievous injury, with its tour finished VMF-214 was deactivated and its pilots reassigned to spread their expertise. A reconstituted unit did not fare so well on its return to combat. The Black Sheep who went to war in 1945 never got the chance to live up to their legacy, but they lived up to their name. Mostly fresh out of flight school, they lost 11 Corsairs and seven airmen during training to collisions, disappearances and freak accidents. One pilot’s life raft ballooned inside the plane, shoving him out of the cockpit at 5,000 feet without his chute; another had a fatal tangle with an aerial towed target banner; a third’s belly tank tore loose on a carrier landing, hit his prop and exploded, immolating him in the cockpit. Even their mascot, a black lamb named Midnite, was run over by a car and killed; Midnite II proved to be an ornery ram with a penchant for butting heads with squadron mates.

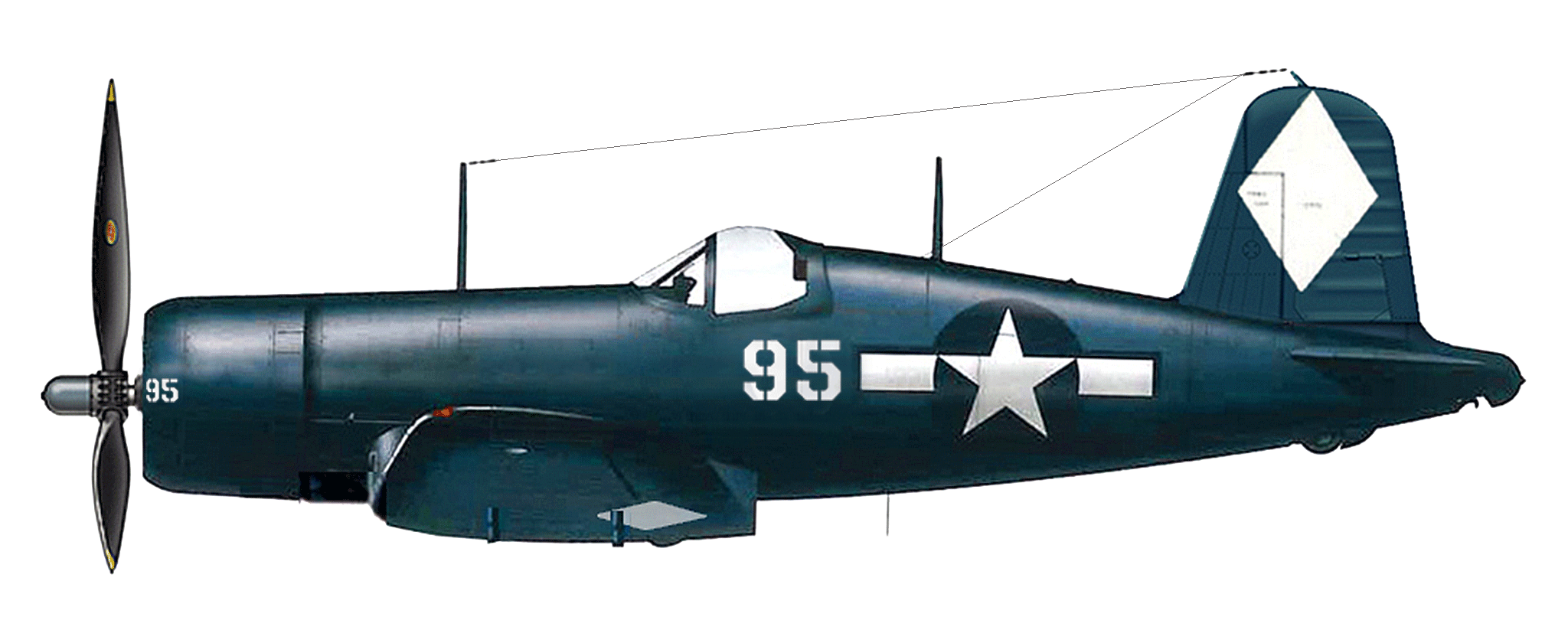

F4U-1D Corsair, VMF-214 The Corsair had changed too. Finally cleared for carrier ops, the new F4U-1D could pack 1,000 pounds of high-explosive or napalm bombs, eight five-inch HVAR (high-velocity aircraft) rockets or a centerline-mounted 11.75-inch “Tiny Tim” missile. All these weapons were stocked when VMF-214 boarded CV-13, the Essex-class carrier Franklin. Sailing as part of Task Force 58 in support of the Okinawa invasion, “Big Ben” would make the closest approach to the Japanese Home Islands of any U.S. carrier in the entire war: just 50 miles, a mere 10–15 minutes’ flying time, off southern Kyushu. At dawn on March 19, Franklin had more than 30 aircraft on deck and 22 below, readying for a strike into Japan’s Inland Sea. Many VMF-214 pilots were prepping for their mission in the squadron ready room above the hangar deck when, at about 0705 hours, a single Japanese plane (usually described as a Yokosuka D4Y3 “Judy”) dropped out of the low cloud cover, crossed the ship bow to stern at mast height and pickled off its ordnance dead center. At least one 550-pounder punched through the flight deck into the crowded, busy hangar deck below and exploded.

USS Franklin, March 19, 1945 In the confined space, the blast redoubled. Burst tanks and lines spattered aviation fuel. Bombs and rockets set each other off. The rippling explosion was so powerful it heaved the entire 32-ton forward aircraft elevator clear up out of its well. The flight crews in the hangar deck never knew what hit them. Concussion bucked the overhead ready room so hard the floor broke pilots’ legs where they stood or hurled them bodily against the overhead. Some jumped or were blown overboard several stories down into the icy water. Few escaped uninjured as flames ravaged the listing carrier stem to stern, punctuated by ordnance cooking off. More than 800 men died, with almost 500 wounded. The tale of Franklin’s epic, and ultimately successful, battle for survival has passed into U.S. Navy legend, but 32 men of VMF-214 never lived to fight it, let alone fight the enemy. For both Big Ben and the Black Sheep, World War II was over.

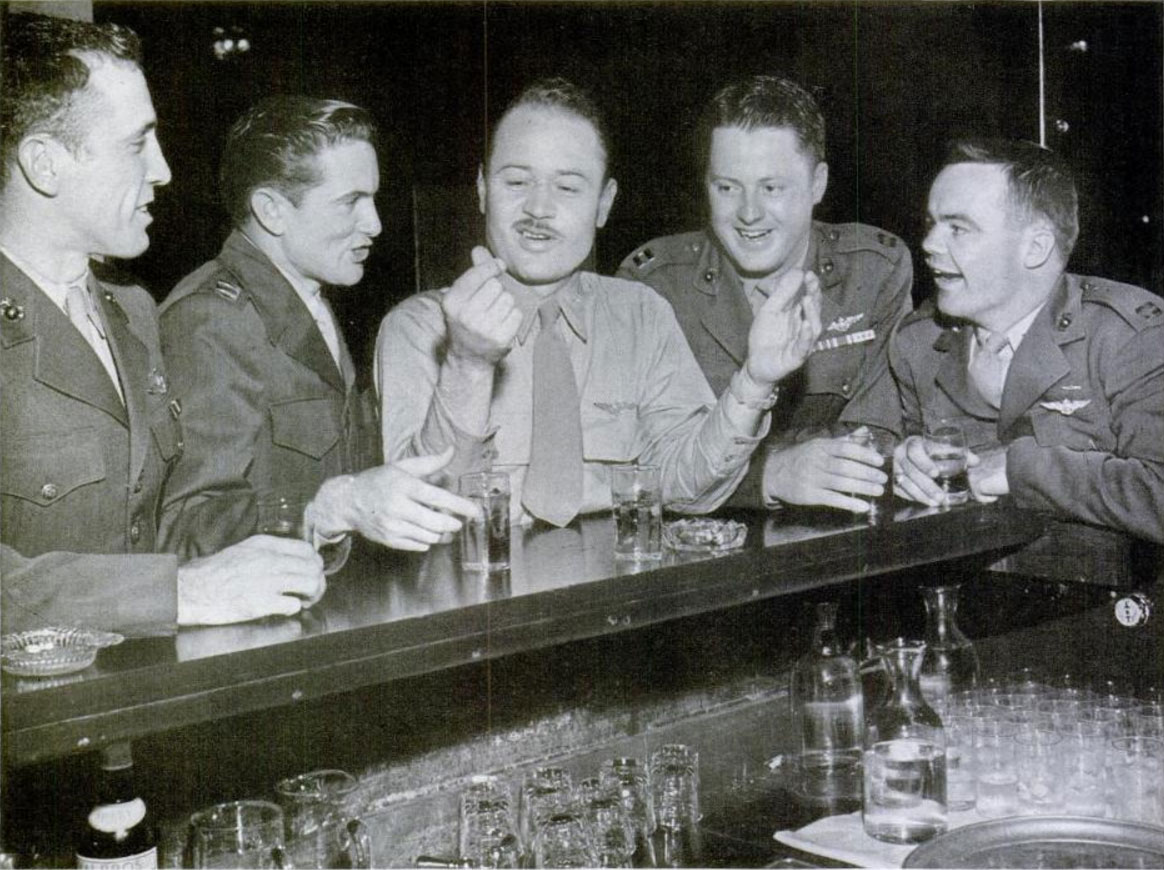

In late 1945 Boyington (center) reunites with Black Sheep comrades, including Chris Magee (left) and Bill Case (right) in the bar at San Francisco’s St. Francis Hotel. In August 1945, the survivors were preparing to muster out when word came that Boyington was not only alive but now considered the top-scoring Marine ace of the war, having claimed two more Zeros on his last mission before going down in the ocean. (Today official sources credit him variously with between 22 and 28 victories.) He’d been picked up by a Japanese sub, and spent the rest of the war as a POW. That October, President Harry S. Truman awarded Boyington his “posthumous” Medal of Honor on the White House lawn, but not before Pappy had his promised reunion with the Black Sheep—one so legendary that it’s said to be the first bender to rate a photo feature in Life magazine.

“The Homecoming” by John D. Shaw What America knows as the Black Sheep Squadron flew together as a unit for only about three months—less than one 13-week television season—but destroyed 97 enemy aircraft, with 35 probables and 50 damaged, plus almost 30 ships sunk. Of the 28 pilots on their first tour, no less than nine became aces. Bolt went on to score six kills in Korea for 12 total—the Marine Corps’ only jet ace and only ace in two wars—while Magee flew Messerschmitts for the Israelis, bootlegged booze and robbed banks. One of the few WWII-vintage squadrons still serving today, VMF-214 flew Corsairs in Korea, A-4 Skyhawks in Vietnam and AV-8B Harrier jump jets in Iraq and Afghanistan. Over the years the forlorn black sheep on the squadron insignia, which a bunch of orphan flyboys first scribbled up on Guadalcanal, has become a proud, foot-stamping ram. And no matter what they fly, their crest still bears a Bent-Wing Bird.

About the authorAuthor/illustrator/historian Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Military Heritage, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His work is also available in paperback, hardcover and across the internet, a number of which rank extremely high in global search rankings. More from Don Hollway:

|