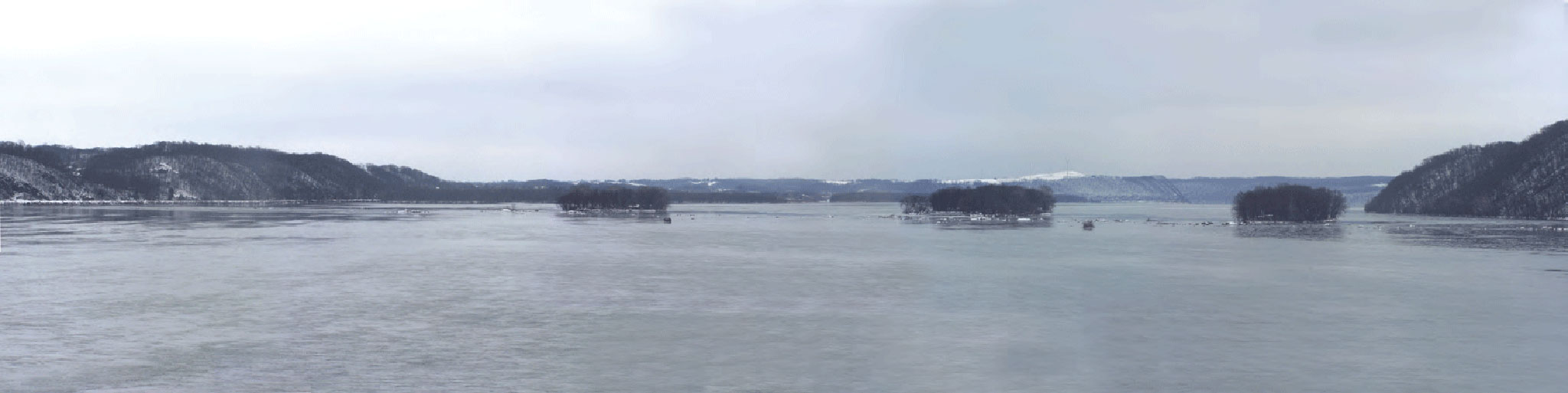

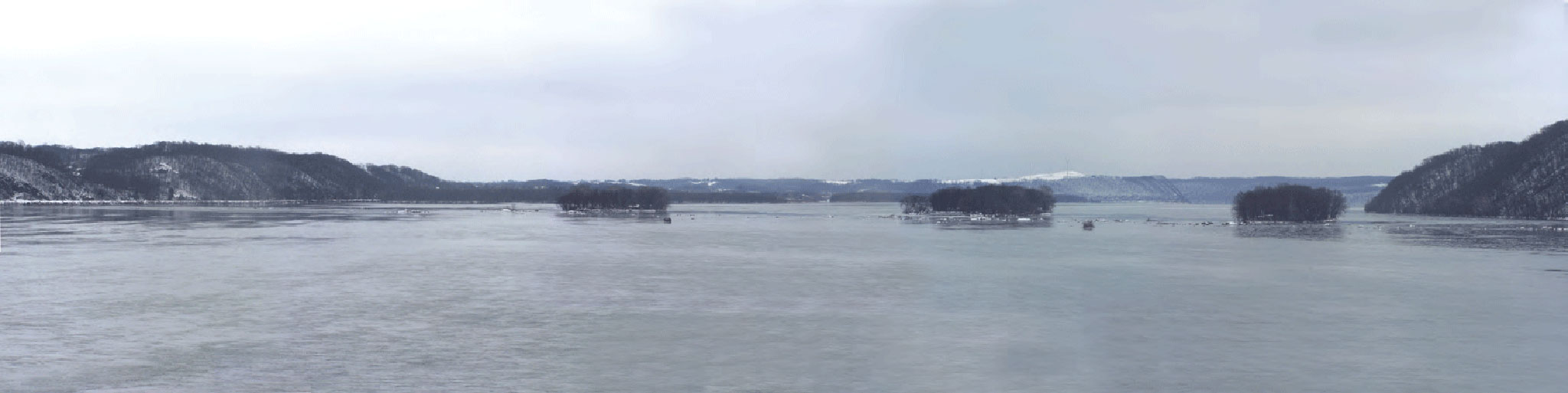

View of Lake Clarke, Susquehanna River, looking south. In colonial days this was the Conejohela Valley, a seasonal floodplain. Though two of the later Susquehannock villages are behind the high ground at right, most are on the low ground, center distance, where the river bends gently to the right before hooking left behind Turkey Hill, the snowy high ground at center-right. The Paxton Boys would have ridden along the foot of the hills at left until rounding snow-capped Turkey Hill, where they turned inland to Indian Round Top.

Find it

Monument at site of first Conestoga Massacre, which occured about 400 yards to the west.

Find it.

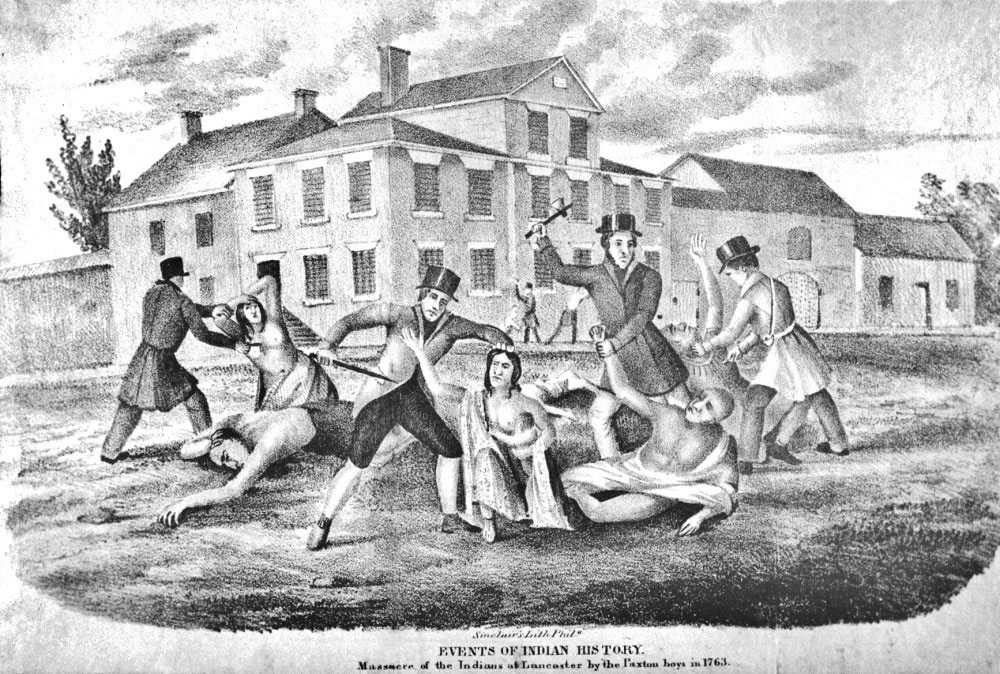

Before dawn on a cold, snowy Wednesday in December 1763, some fifty heavily armed Pennsylvania settlers saddled up in Wrights Ferry (modern Columbia) and rode out with murder in their hearts. Just a few miles down the east bank of the Susquehanna River they turned inland, up a height called Indian Round Top, to a small hamlet of European-style cabins sleeping peacefully in the snow. It took the riders only a few minutes to dismount, unlimber their weapons and break into the cabins, where they rolled a half-dozen old men, women and children from their beds and killed them all. When done with their flintlocks and tomahawks, they set to with their scalping knives. After that they looted the huts and burned everything to the ground. The sun was still rising when they rode for home, grisly trophies flapping from their saddle horns.

Indian Round Top, the approximate location of the first Conestoga Massacre, Dec. 14, 1763

Find it

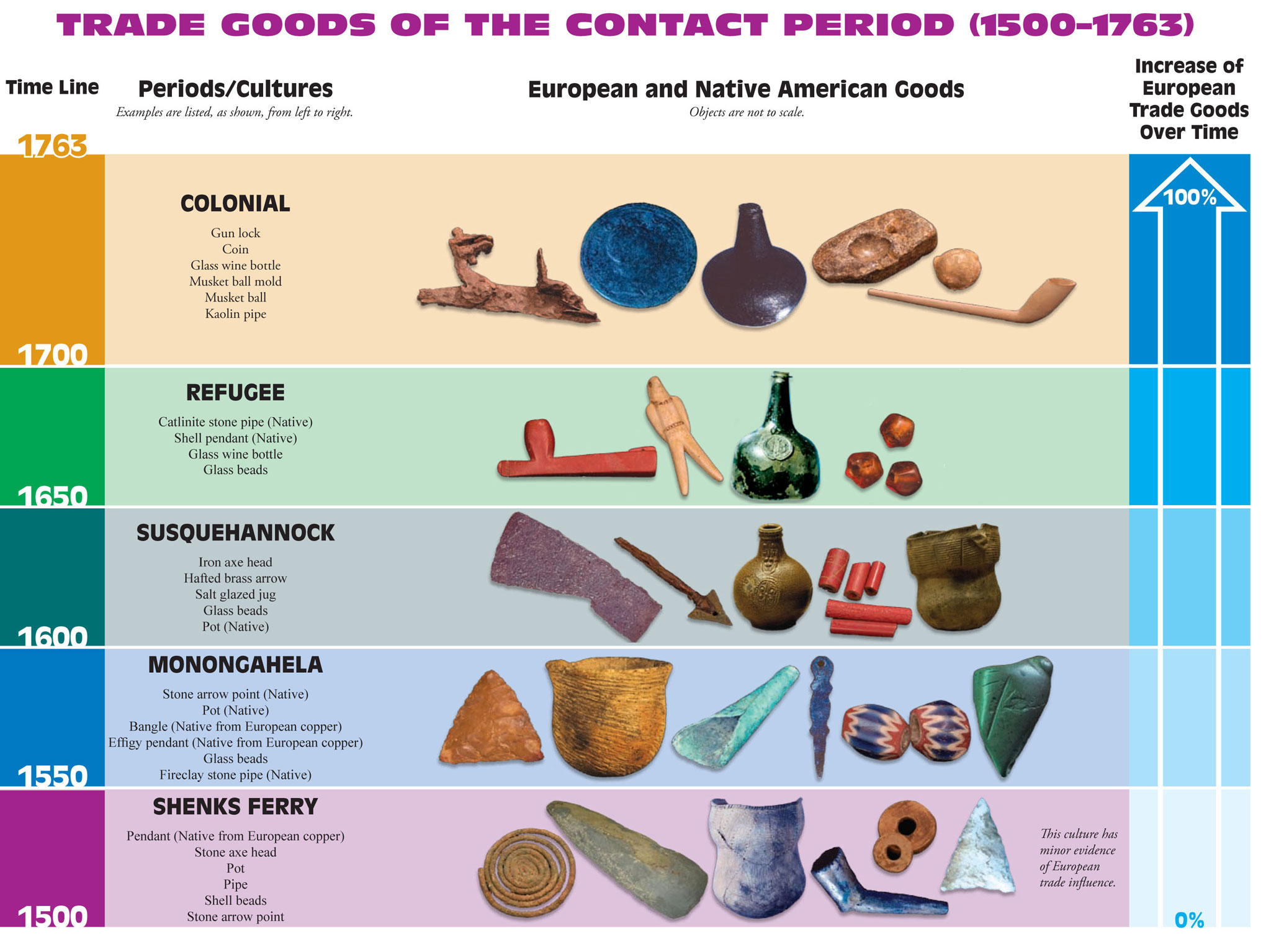

The remains smoking in the bloodstained snow marked a sad end to a brief, bright flash in the historical pan. The dead villagers, known locally as the Conestoga Indians, were among the last of what had once been the most warlike and powerful tribe in the Middle Atlantic: the Susquehannocks. Centuries later we remember little of their culture, only a hundred or so words of their language, and a mere a handful of them by name, but not what they called themselves, “Susquehannock” being an Algonquian word for “People of the Muddy River.” Their artifacts have been found from New York to the Potomac to West Virginia. At their peak they controlled more territory than the Iroquois Five Nations put together, and even briefly conquered what would become New York City. For much of the 17th Century they held the gates of North America itself: the very balance of power between inland tribes and warring English, French, Swedish, and Dutch—not to mention feuding Pennsylvanians, New Yorkers, Marylanders, and Virginians.

Analysis of their surviving vocabulary links it to Iroquois, and even determines the two languages (and peoples) diverged around 1000 AD. Archaeologists date proto-Susquehannock pottery to circa 1450 along the New York-Pennsylvania border, and their distinct relics in the same area a century later. What is known of their lifestyle conforms to the Iroquoian, with multiple families living in longhouses rather than Algonquian-style wigwams, and probably a matriarchal, matrilineal society, with maternal uncles rather than biological fathers playing the dominant male role.

That they became a unique people around the end of the Medieval Optimum and the onset of the Little Ice Age may also explain why they did not become part of the great Iroquois confederation. Competition for newly limited resources contributed to the disintegration of even the great cities of the Mississippi mound-building agricultural empires, and perhaps the ritual cannibalism infamous among Iroquoians. It may have compelled the unification of the central Five Nations and expulsion of the outlying Susquehannock and Huron.

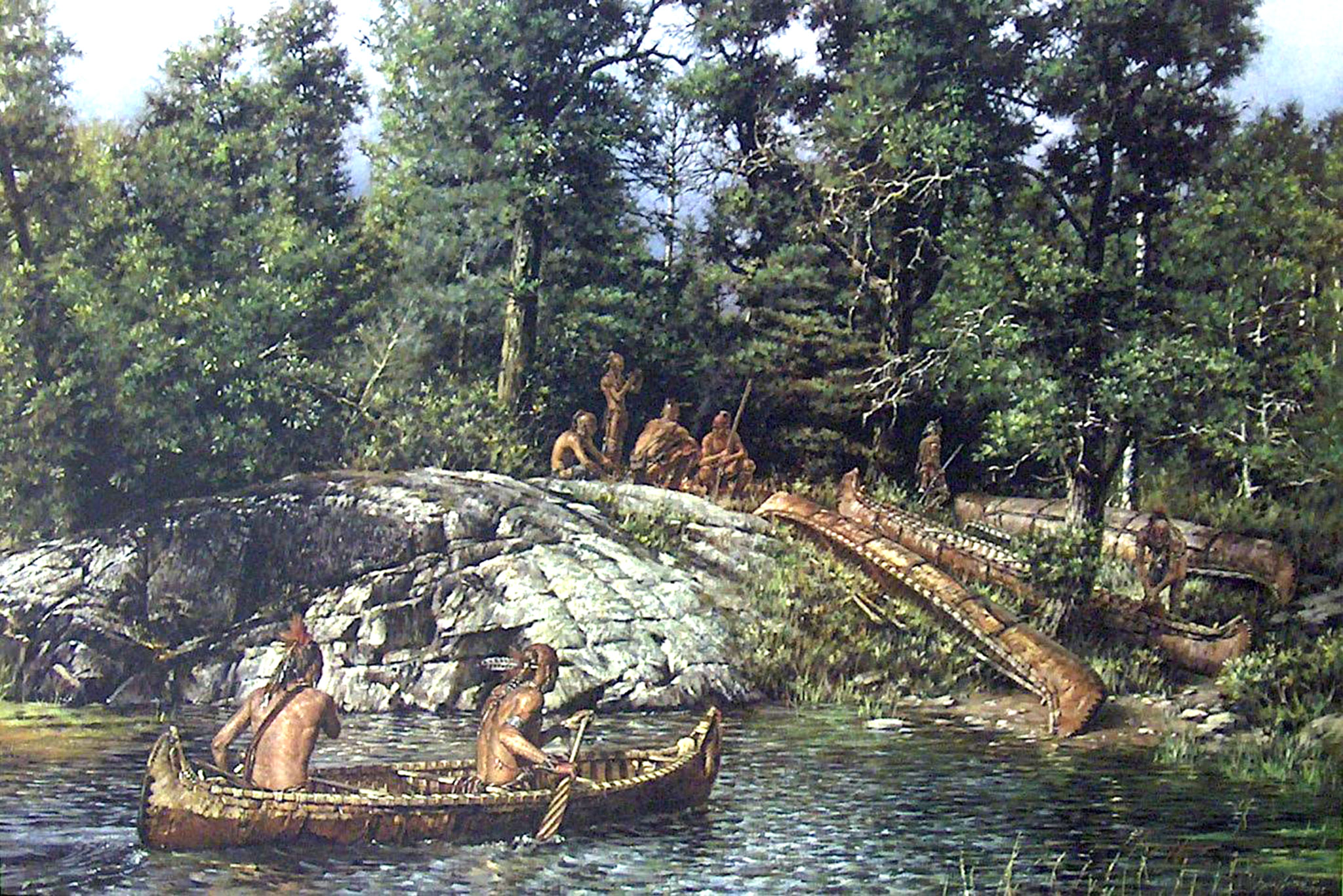

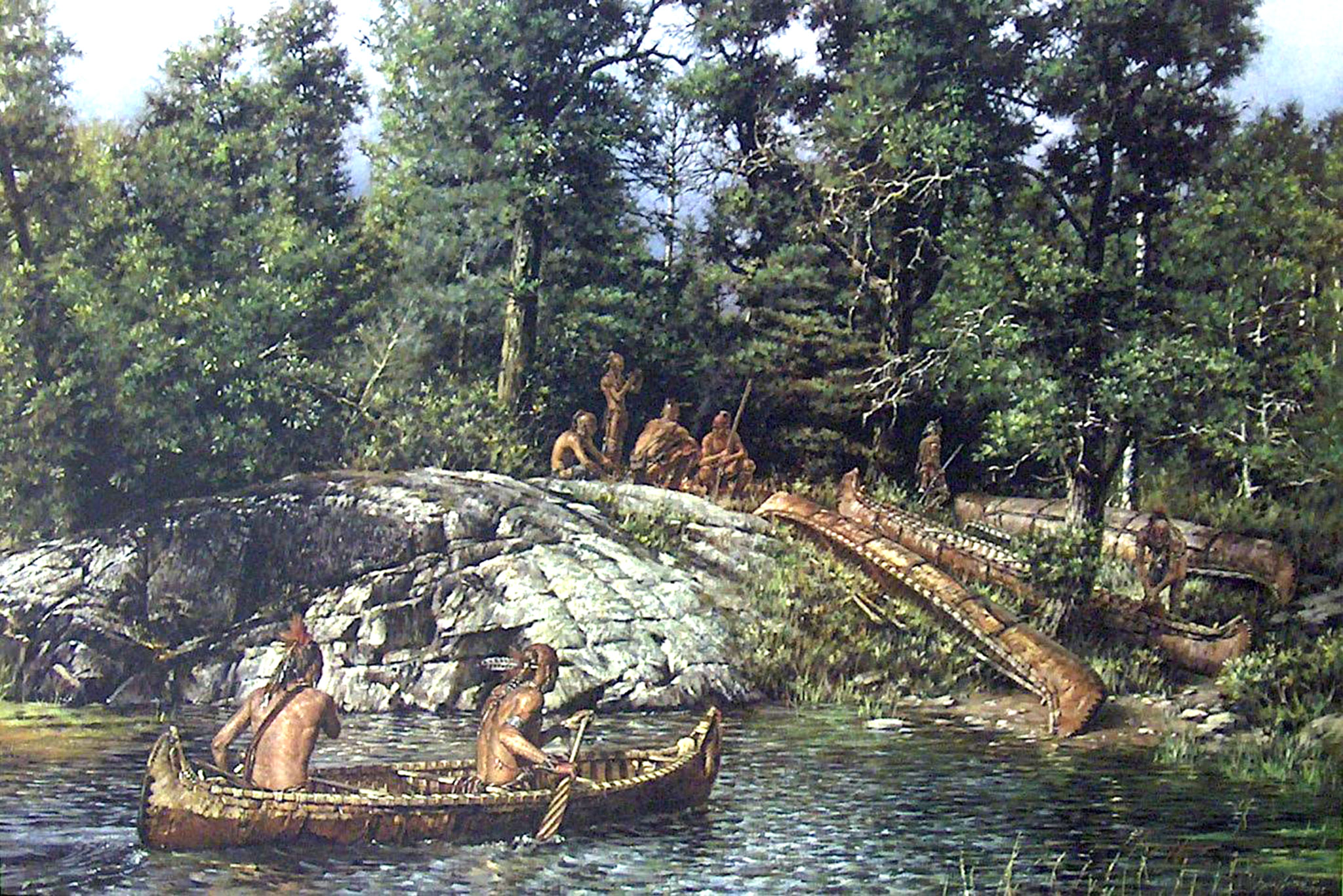

Late Arrivals, by Robert Griffing

Buy it

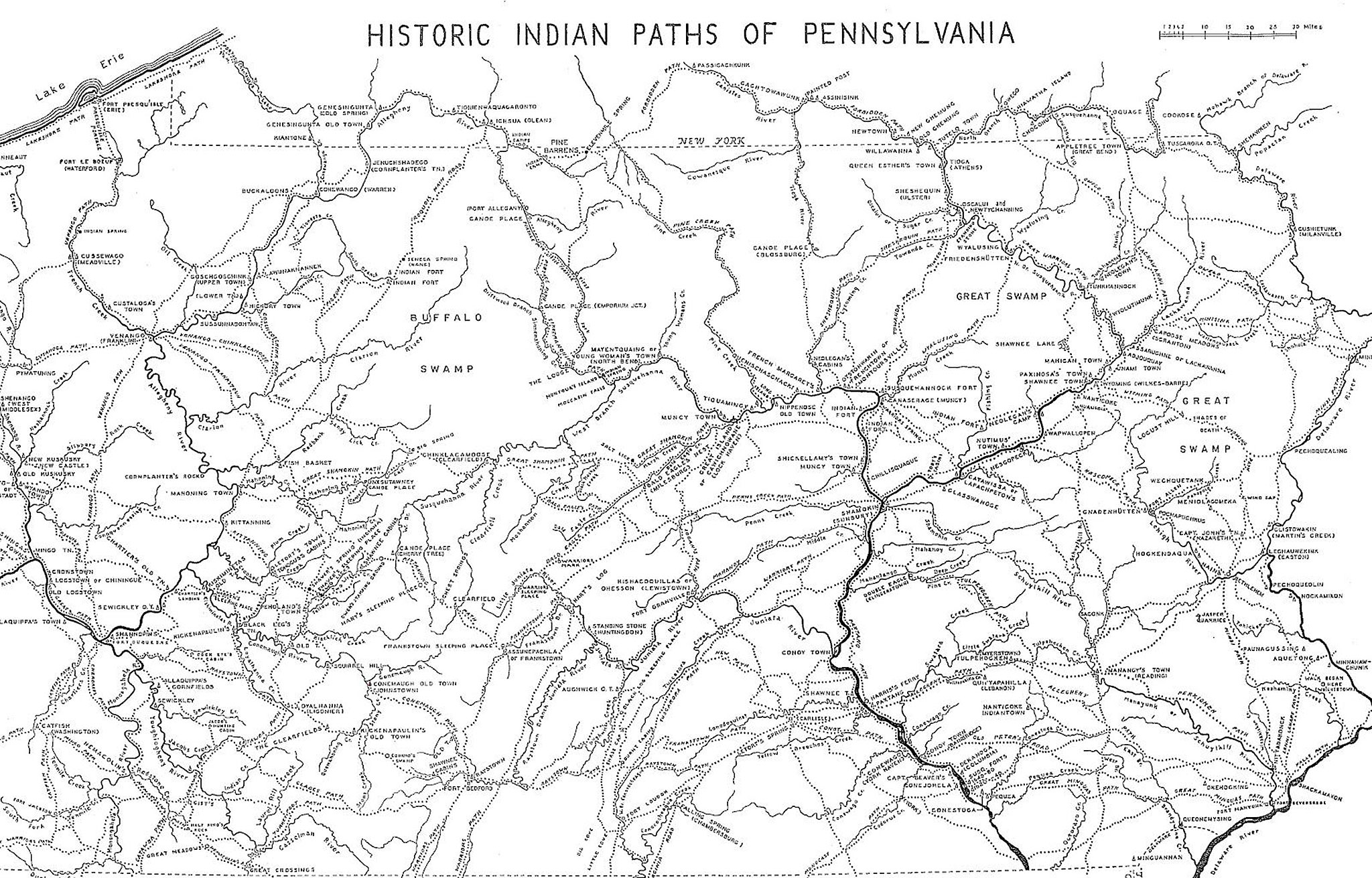

Over the course of the late 1500s, possibly under pressure of conflict with the Mohawk (years later French Jesuit missionaries in Canada learned that in these decades the two tribes carried on a running war of extermination, which the Mohawks nearly lost), the Susquehannocks migrated south. The Pennsylvania they found was very different from ours: the undammed river running with ocean-migratory shad and eel, not to mention beaver, otter, marten and fisher; forests thick with oak and hickory, but also towering white pine and American chestnut; probably fewer, more heavily hunted whitetail deer, but many more native elk, moose and bison; huge flocks of Carolina parakeets and passenger pigeons. With far-flung tributaries reaching to within easy canoe portage of the Delaware, Great Lakes, and Allegheny-Ohio-Mississippi basin, the Susquehanna offered access to half the continent. And near its mouth was the happy hunting ground: the Piedmont of today’s Lancaster County, still some of the nation’s richest farmland.

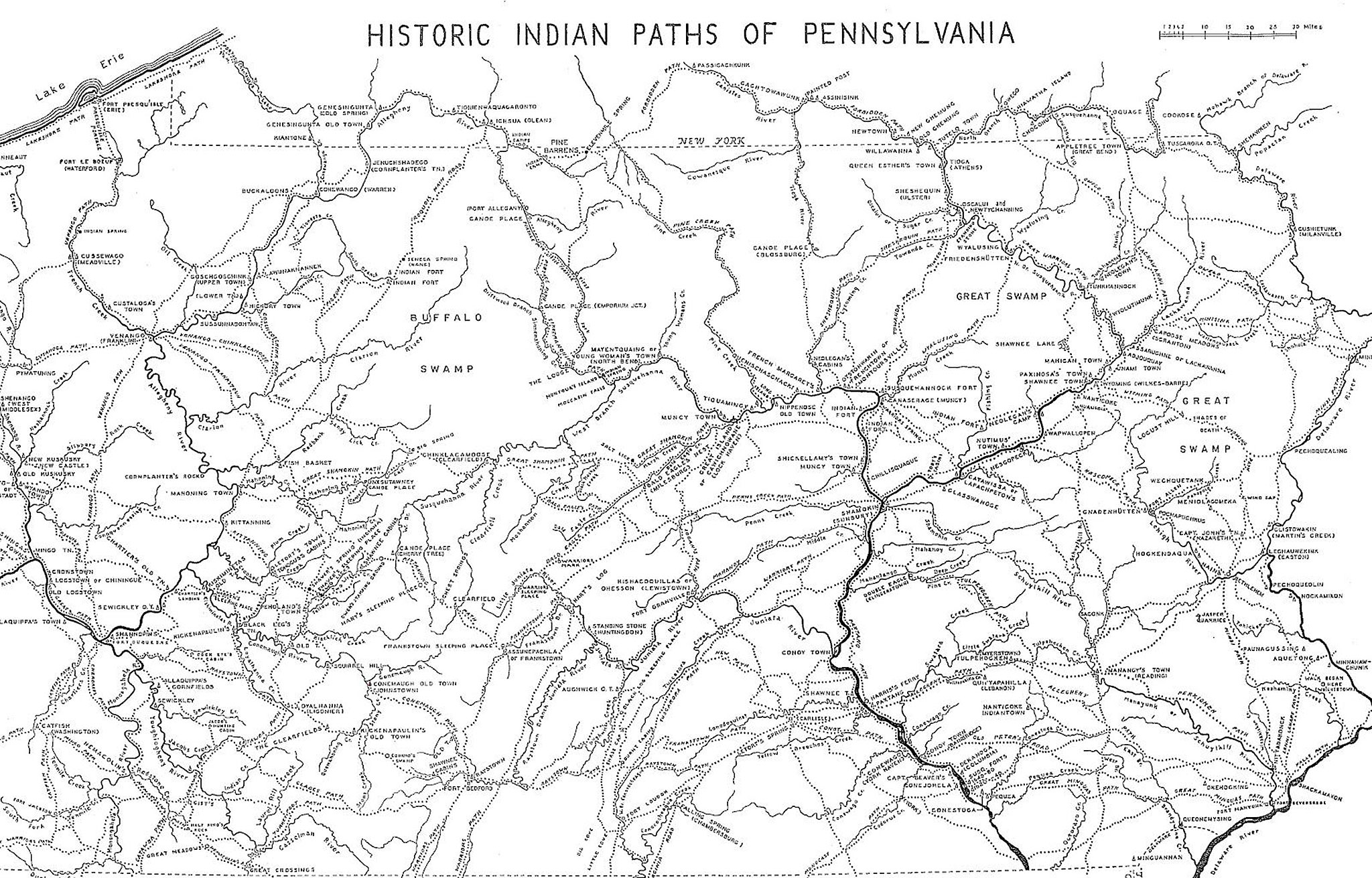

Indian Paths of Pennsylvania

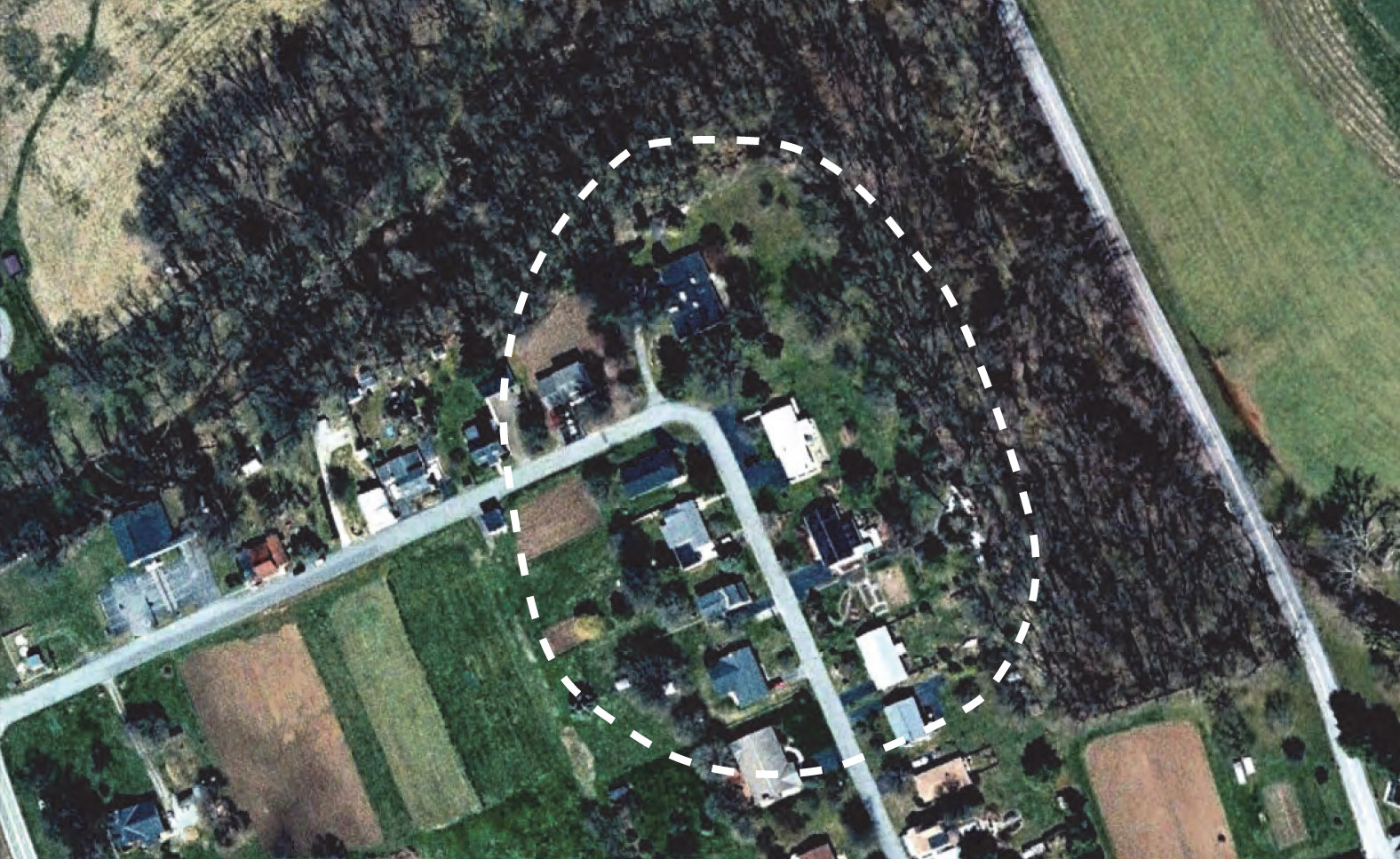

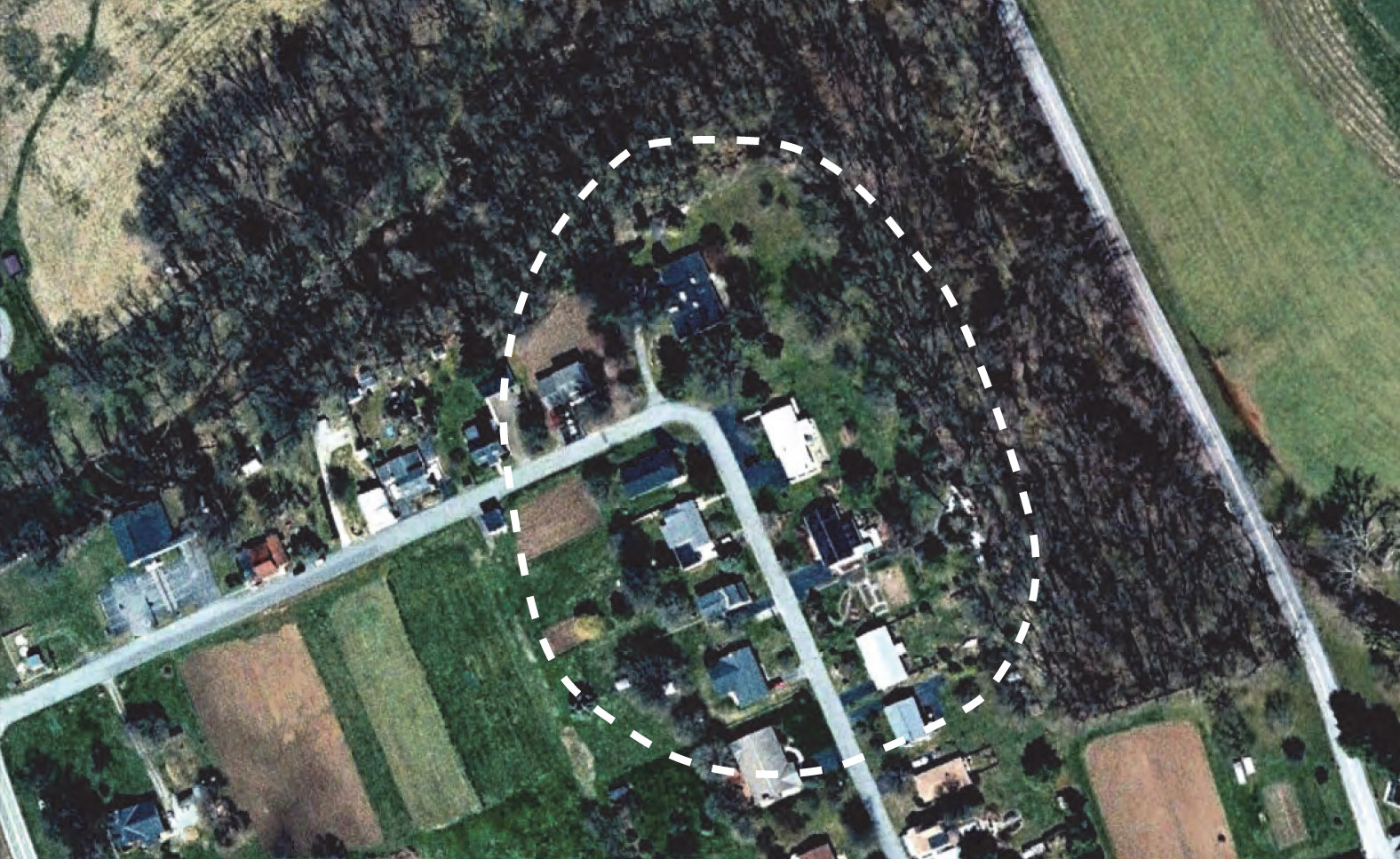

Google Earth view of Elizabeth St (from left) & Mill St (from bottom), Washington Boro PA,

showing approximate outline of Susquehannock stockade, c. 1608

Find it

By 1600 the Susquehannocks had displaced, conquered or absorbed the local Algonquian inhabitants. (There may have been a population vacuum to fill, as lethal new viruses were the first European colonists to spread inland, particularly up such natural byways as rivers.) In the summer of 1608, when John Smith of Jamestown Colony explored the headwaters of Chesapeake Bay, they sent a delegation of 60 warriors downriver to meet him, who claimed to muster ten times that number from five fortified villages up the river.

Susquehannock archaeological sites in south central Pennsylvania:

Roberts (36La1); Shenks Ferry (36La2); Strickler (36La3); Schultz-Funk (36La7); Washington Boro (36La8); Conestoga Town (36La52); Conoy Town (36La57); Oscar Leibhart (36Yo9); Byrd Leibhart (36Yo170)

Only one of these is known (others are thought to lie buried under today’s heavily excavated and paved Susquehanna industrial zones), but numerous earlier and later sites cluster its vicinity. In typical Eastern Woodland fashion, the tribe occupied each until the local soil and wood supply was exhausted, then pulled up stakes and moved just far enough to start afresh. Today the Susquehanna, backed up behind Safe Harbor Dam, flows over these lands as mile-wide Lake Clarke, but in those days it was a seasonal flood plain colonials named the Conejohela Valley, as beneficent to its people as the Nile or Tigris-Euphrates.

Prior to the building of Holtwood Dam, the Susquehanna below Lancaster County’s Pinnacle Point would have been an even deeper canyon. View (looking roughly northwest, upriver) is from about 537 feet above the water. On the left the river is a further 190 feet deep. Susquehannocks from Washington Boro site would have canoed this corridor on their way to meet John Smith, August 1608.

Find it

John Smith of Jamestown

Smith famously described the “Sasquesahanougs” (spelled two different ways on the same map) as “gyant-like.” Warriors raised on corn and venison no doubt appeared so to a scrawny, malnourished Elizabethan. Nor did they meet the Virginians as anything less than equals. The English wore armor and carried muskets, but the Susquehannocks wore the heads of bear and wolves for their jewelry, and already possessed metal hatchets and knives. (European fishermen had been trading along the New Jersey and Delaware coasts for decades; the French had been in Canada since the 1530s and Samuel de Champlain had founded Quebec City just a few weeks prior in that summer of 1608.) The chieftains offered the Virginians food, free passage and their loyalty for help in their generations-long war against the Iroquois. Smith sorely needed such powerful native friends against the French and Dutch, not to mention his own treacherous Powhatan hosts in Virginia, but lamented, “The council [ruling Jamestown] would not think to hazard forty men in these unknown regions. So the opportunity was lost.” It was the Susquehannocks’ first taste of English duplicity.

John Smith’s map of Virginia, engraved by William Hole c. 1609. Available from the Library of Congress

Served as a basis for Henricus Hondius’ 1630 map of the Virginia, with a different “Susquehannock” based on a Powhatan by Thomas de Bry

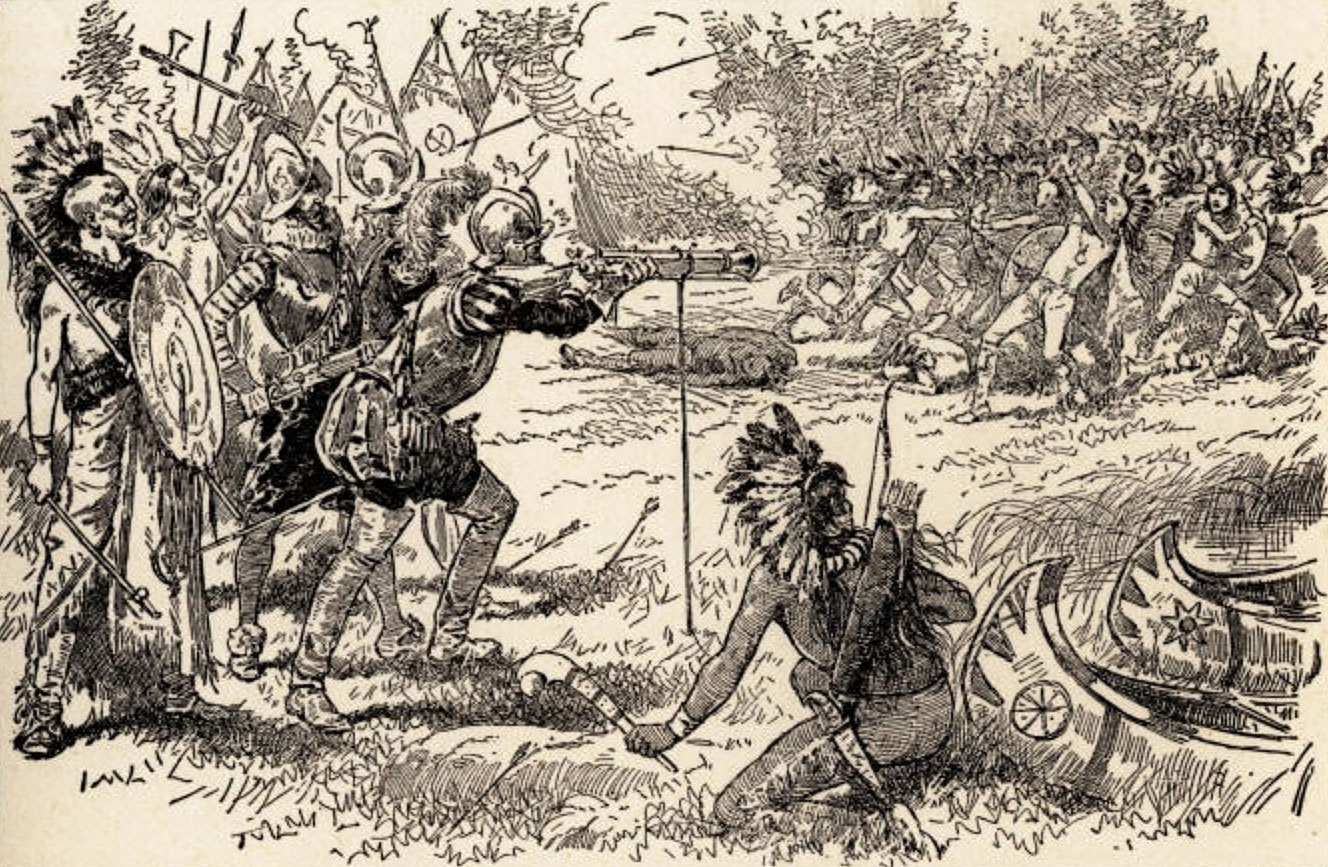

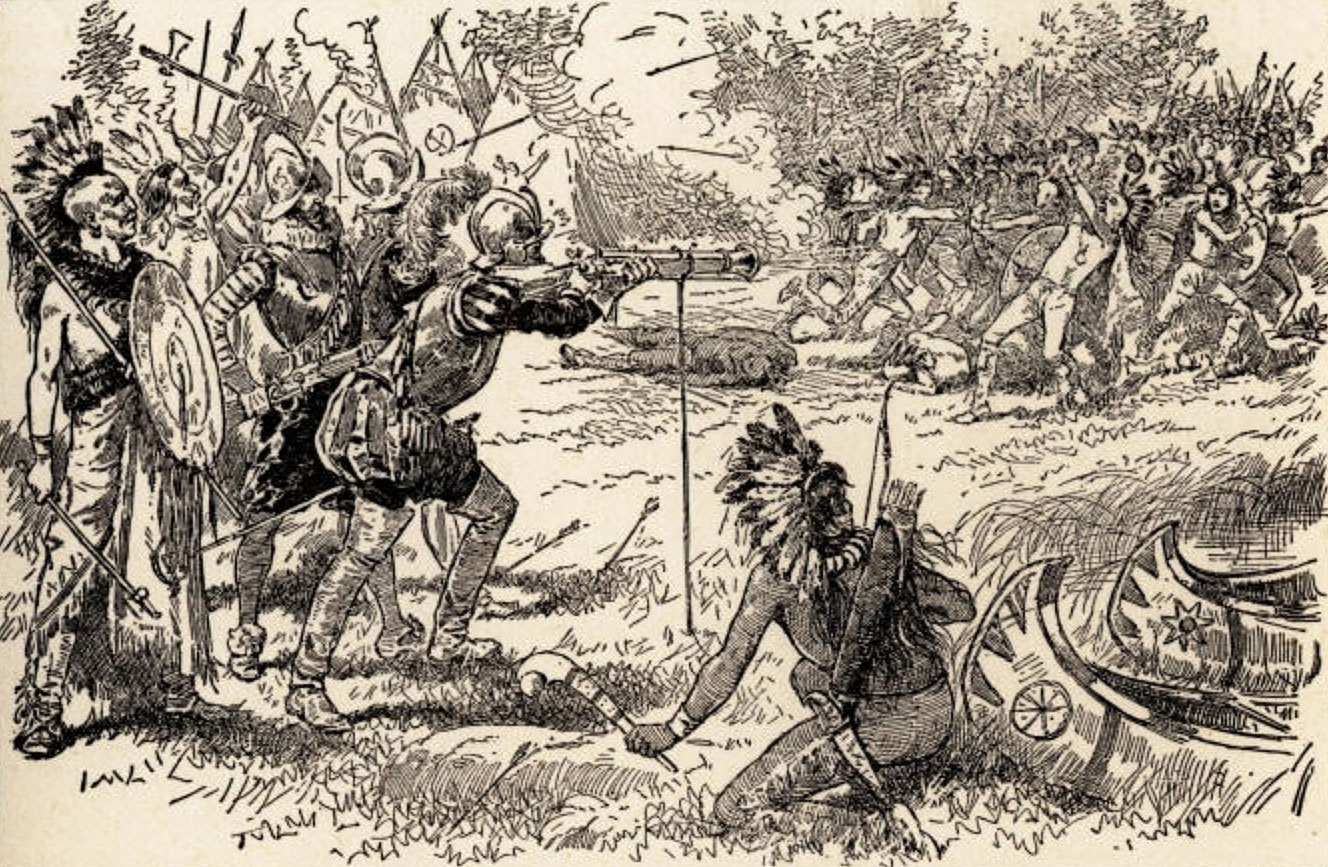

Summer 1609: Samuel de Champlain puts France on the side of the Montganais, Algonquians, and Hurons against their enemies, the Iroquois.

The following summer Champlain made France the enemy of the Iroquois, personally killing two of their sachems and mortally wounding a warrior with one shot of his wheel lock arquebus (having loaded four balls, a dangerous but effective tactic) on behalf of his trading partners, the Huron. In 1615 Étienne Brûlé, his young coureur des bois (explorer/trader, literally “woodlands runner”), became the first white man to travel the length of the Susquehanna. He joined a Huron canoe expedition seeking alliance with a downriver people they called Andastoerrhonon, “people of the blackened ridge pole,” the meaning of which is lost. Though the allied armies arrived two days too late to prevent French defeat at Iroquois hands, Brûlé later reported these “Andastes” or “Andastogues” mustered some 800 warriors. One of their lost villages, Carantouan, is reputed to have been atop the glacial drumlin called Spanish Hill, just east of the Chemung River and south of the New York border in modern South Waverly, PA, though most archaeological evidence there dates from pre-Columbian times.

This 230'-high glacial drumlin at South Waverly, PA, called Spanish Hill, has variously been thought to been an artificial construct of Mound Builder culture or the site of a last stand by a lost band of conquistadors. It was almost certainly visited by Champlain’s emissary, Étienne Brûlé, c. 1615. Most remains are pre-Columbian. Today the site is private property.

Photo courtesy of SpanishHill.com

Find it

If the Frenchman reached the Chesapeake in 1615 he must have found it increasingly crowded. Virginians had moved as far up the bay as Kent Island, and Dutch were probing down the South River (Delaware). With the Huron allying with the French, the Iroquois with the Dutch, and the Susquehannocks with the English, a certain balance of power might have been expected. Yet the European craze for beaver-felt hats that had driven the species to near-extinction in the Old World was about to do the same in the New, and to several native peoples as well. Not enough fur to go round, and too much black powder; the combination would trigger one of the longest, bloodiest, and least-known conflicts in North America: the Beaver Wars.

Jamestown settlement

The English at Jamestown, stocking several hundred matchlocks and a smattering of snaphances and wheel lock pistols for officers, took pains to keep guns out of native hands. Not that the matchlock held much appeal to the natives; in massed infantry formations it had made armor obsolete and revolutionized the European battlefield, but with its low rate of fire, not to mention match cords stinking of sulfur by day and glowing by night, it was not suited to the Indian methods of surprise and ambush, and useless in the hunt. No matchlock remains have been found in Susquehannock digs.

Delaware Indian family. Swedish artist Thomas Campanius Holm had never visited North America, but based his work upon descriptions written by his grandfather Johannes, who had lived in New Sweden in the 1640s.

It was the Dutch who set off the arms race. Less settlers than traders, it behooved them to stir up competition among natives and Europeans alike. The Lenape of Delaware offered no great business opportunity. Their name for Susquehannocks, “Minqua,” meant “treacherous,” but the Lenape were hardly paragons of virtue; in 1632 they wiped out the first Dutch colony in Delaware, Zwaanendael (“Swan Valley,” modern Lewes), to the last man. In the Susquehannocks, however, the Dutch found partners both willing and able, if only slightly more trustworthy.

“Thousands of beavers can be bought thereabout from the Minquas,” Dutch tradesmen on the Delaware reported. “As soldiers they are not honorable; but accomplish their success by perfidy and treachery.... They know little of God. They are in dread of the devils, but their devils they say will have nothing to do with the Dutch.”

The fur trade was the great impetus of North American exploration

As early as 1623 Dutch arms dealers and military advisors lived among the Susquehannocks, as an English report accused, “to have furnished the Indians with fire arms and to have taught them to use them, that by their assistance they might expel the English when they began to settle around them.”

Excavations near Washington Boro PA, dated circa 1630, proved deals were being done in state of the art weaponry. Archaeologists uncovered the remains of flintlock pistols and parts for wheellocks, doglocks, snaphances and even a Mediterranean-style miquelet. (The Susquehannock word for “gun” was karawda.) No doubt the Dutch hoped to divide their native fur suppliers. Instead they gave the Susquehannocks the means to a monopoly.

Captain David Pieterszoon de Vries

The Lenape were first to be cut out of the loop. Little over a year after discovering the burnt-out remains of Zwaanendael, Captain David Pieterszoon de Vries landed at Fort Nassau (New Castle, Del.) and was met not by Lenape but a war party of some 600 Susquehannocks. Local refugees reported these had laid waste to all the tribes on the Delaware, plundering corn, burning huts, slaughtering many and driving all others before them.

Dutch sailors meet the natives

“They were friendly to us; but it would not do to trust them too far,” logged de Vries. He took the precaution of anchoring in mid-river, “...so they could not come upon us on foot and master us.”

In July the next year English Captain Thomas Yong, searching the Delaware for a Northwest Passage, found the inhabitants fleeing in terror at his approach, except for one who reported, “the people of that River were at warre with a certaine Nation called the Minquaos, who had killed many of them, destroyed their corne, and burned their houses; insomuch as that the Inhabitants had wholy left that side of the River, which was next to their enimies, and had retired themselves on the other side farre up into the woods, the better to secure themselves from their enimies. [sic]” The Lenape would henceforth serve as “women” (in a matriarchal society, not as pejorative as it sounds) and look to the Susquehannocks as “uncles”—in European terms, overlords.

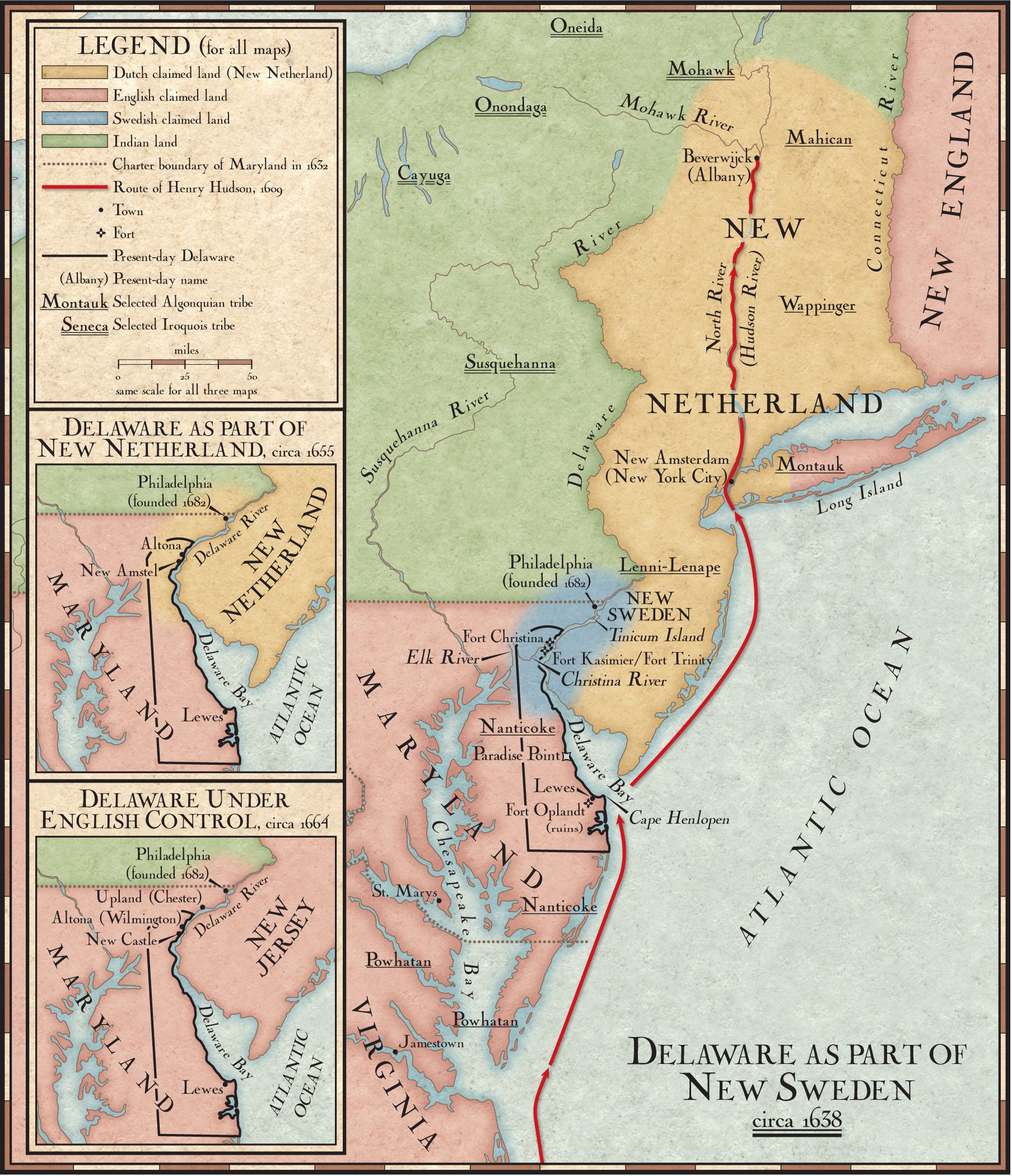

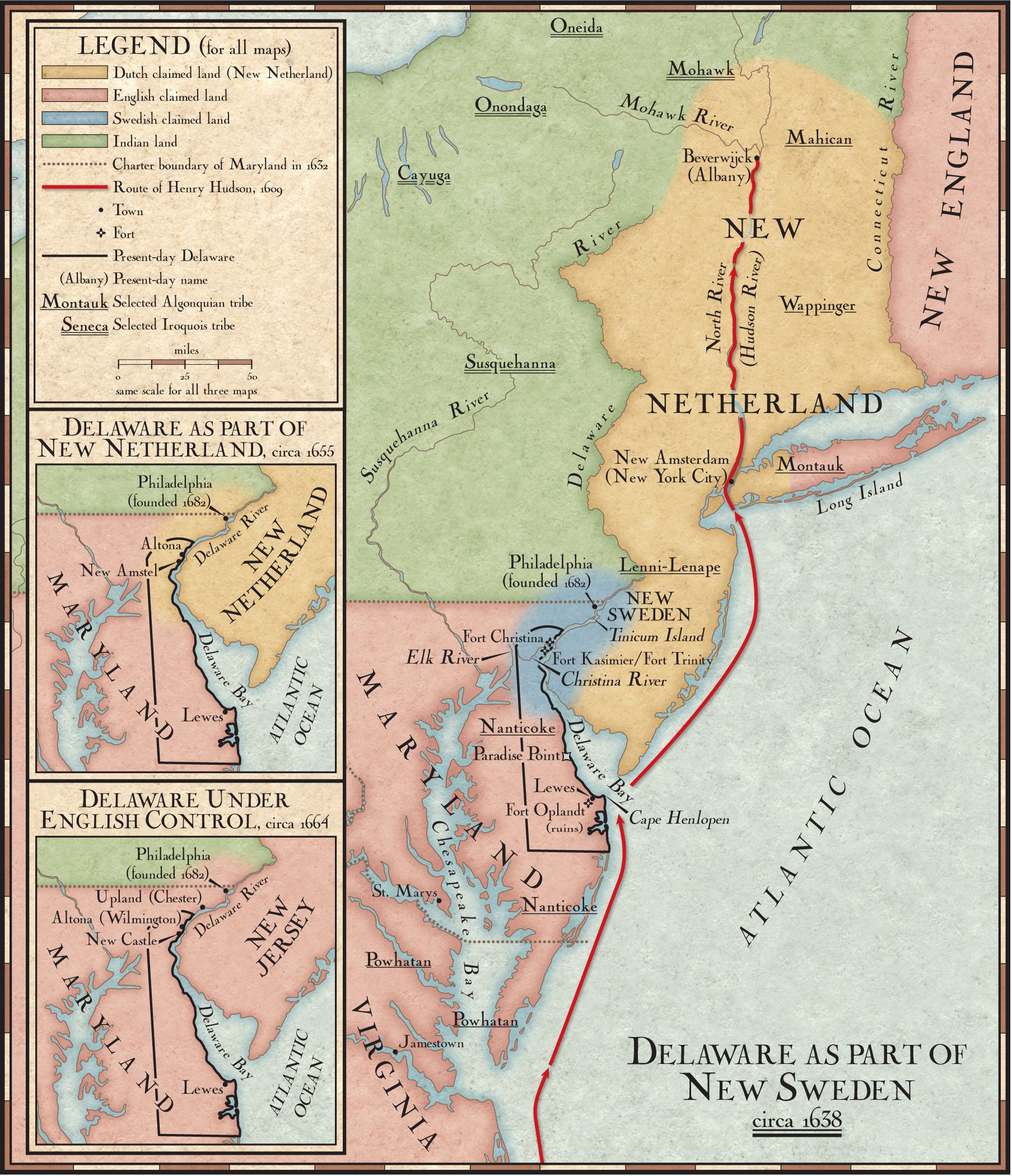

Delaware changes hands, 1638–64

Even as the Susquehannocks rose in the south to dominate the native end of the fur trade, the European side was becoming ever more competitive. If the 17th Century was a chess match played across the map of the world, then it was with multiple opponents around the board, their alliances constantly changing: Swedes vs. French, French vs. Dutch, Dutch vs. English, English vs. English.

.jpg)

Landing of the Swedes, 1638, by Stanley M. Arthurs

Back in 1626 Peter Minuit had bought Manhattan Island from the Lenape on behalf of the Dutch; in 1638, sailing into Delaware Bay to found Ft. Christina (modern Wilmington, Del.) he bought land by permission of the Susquehannocks, on behalf of the Swedes. Having very nearly won the Thirty Years War sixteen years early, their country was at a peak of power and expansion not seen since Viking days. King Gustavus Adolphus died on the battlefield at Lützen in 1632, but his ministers carried on his plans for a New World fur and tobacco empire at the expense of the English, Dutch and French.

It was a Swedish missionary, Johannes Campanius, who compiled what little we know of the Susquehannock language. He arrived at New Sweden in 1643 and lived there until 1648. In that time he came to well know the Susquehannocks, but tried to ignore their Iroquoian ways. “When the Swedes first arrived,” he wrote, “the Indians were in the habit of eating human flesh...they generally eat that of their enemies after broiling it.”

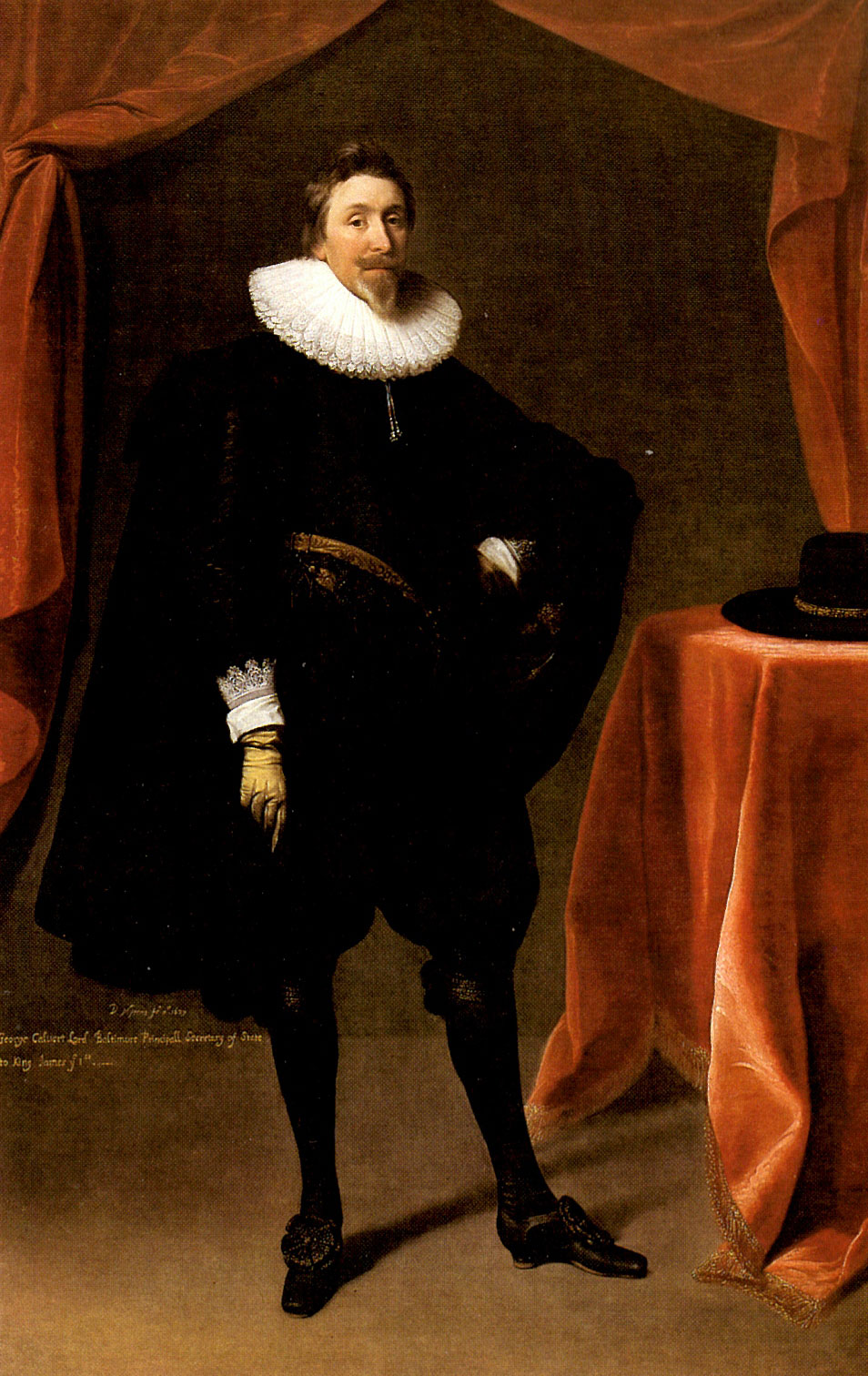

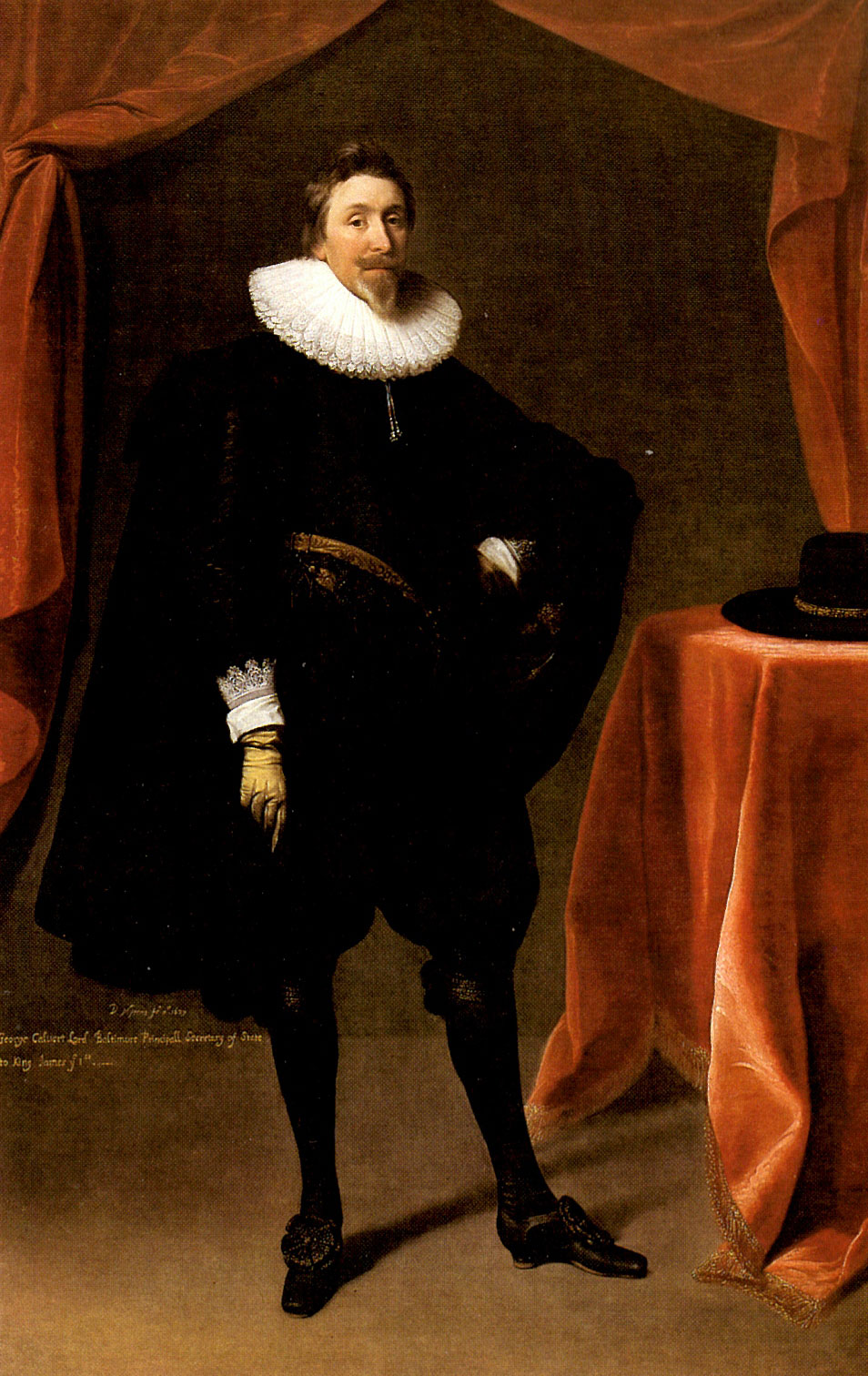

George Calvert, 1st Baron Baltimore

To the south, English traders on Chesapeake Bay’s Kent Island avoided Susquehannock cook-pots by encouraging them to terrorize the local Wicomico, Piscataway and Patuxent tribes. The Virginians’ bigger problem was that they were no longer the only English in the Chesapeake. King Charles I had ceded to George Calvert, Lord Baltimore, the Delmarva Peninsula up to the 40th Parallel. Named after the king’s unpopular French Catholic queen, Henrietta Maria, the new colony was intended as a papist sanctum, much to the displeasure of Protestant Virginians. Indians and islanders began to run so roughshod over the Eastern Shore that the Marylanders took Kent Island by force, declared the traders outlaws and the Susquehannocks, “the boldest and most warlike of all the Indians now engaged in hostilities against our colonies,” public enemies to be shot on sight.

Defeating Virginians was one thing, Susquehannocks another. Requiring every able-bodied citizen to bear “one serviceable fixed gunne, of bastard musket bore [i.e., between that of a heavy musket and light caliver]...a sufficient quantity of match for matchlocks and flint for firelocks and...a sword and belt for every such person aforesaid” under penalty of 30 pounds of tobacco per violation, in 1639 Maryland raised a military expedition to “be sent against the Susquehannocks, sufficiently victualed and manned, and thirty or more good shott with gunn or pistols.” Alas, enthusiasm for the mission ran out “upon receipt of intelligence that the Susquehannocks were supplied with firearms.”

Naturally this called for an escalation in force. During 1643-44 Capt. Thomas Cornwallis, victor of Kent Island (a great-uncle of Gen. Charles Cornwallis of Yorktown fame), led another expedition upriver, this time armed with falconets: light antipersonnel field guns. On first encounter artillery fire gave the Susquehannocks a shock, but when time came for a rematch they had gotten over it. Fleeing, the English left behind numerous dead, fifteen prisoners, and two cannon. Offers to ransom the captives met with ridicule from the Indians, who celebrated victory by torturing them to death. Maryland called it quits. That June, at Piscataway along the Potomac River, the two sides declared an uneasy truce. To commemorate the occasion Maryland presented the Susquehannock chiefs with a copper medallion with a black and yellow ribbon.

“Mutual Trust” by Paul Domville

State Museum of Pennsylvania

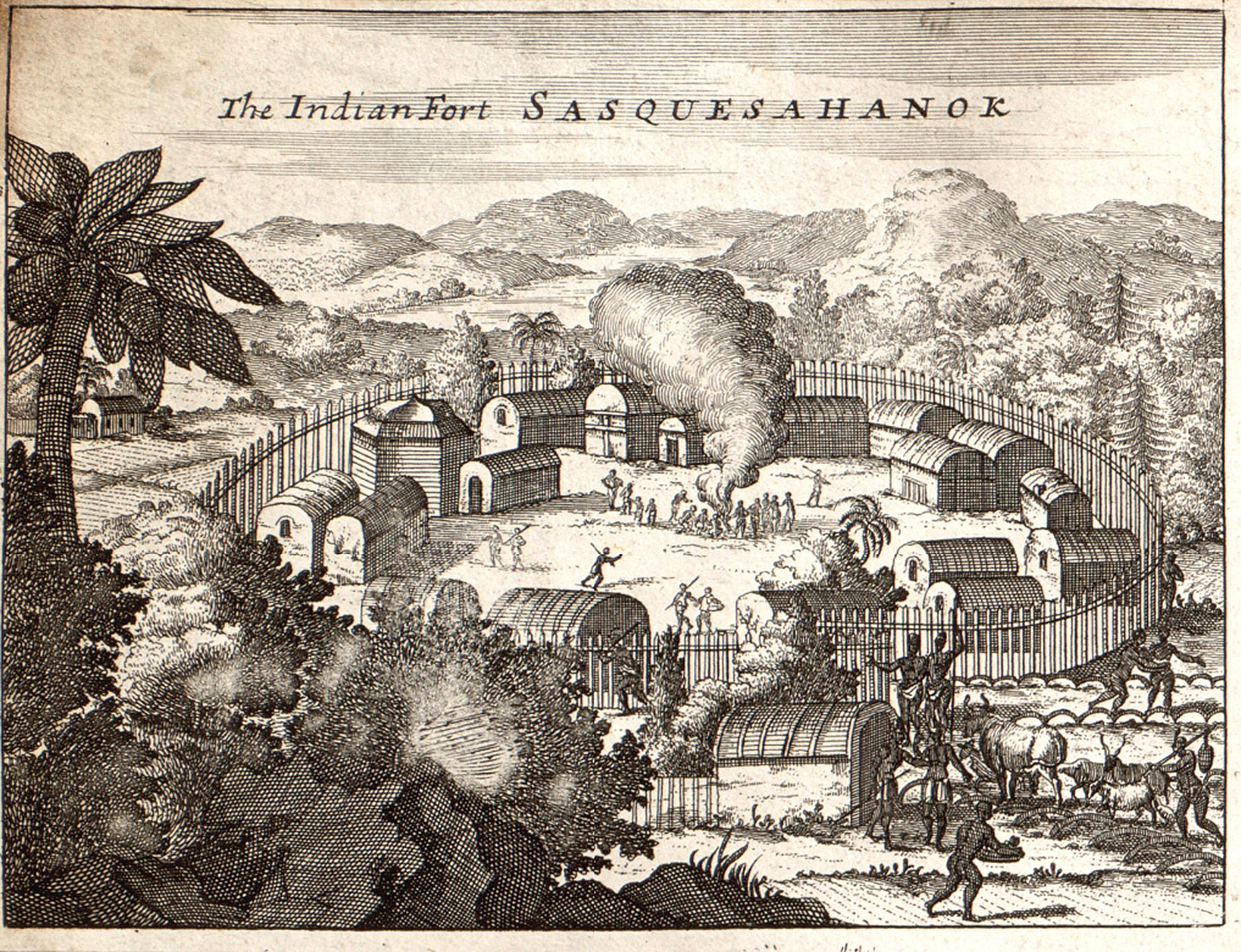

Having secured themselves against the English, and with the Dutch and Swedes competing for their good will, the Susquehannocks were near the height of their power. Campanius tells us, “They live on a high mountain, very steep and difficult to climb; there they have a fort...surrounded with palisades...guns and small iron cannon, with which they shoot and defend themselves and take with them when they go to war.”

This Roberts site is thought to be atop a bluff above a horseshoe bend in Lancaster County’s Conestoga Creek. On private land, it’s currently inaccessible, but limited digging in 1971 uncovered flintlock parts and iron knives. The site’s small size and estimated population (900) indicate that it may have been one of several coexisting villages, possibly a forward outpost on the “frontier” with New Sweden. Contemporary burial items nearer to Washington Boro included more flintlock parts, rapier blades (many cut down into daggers) a Swedish cabasset helmet from the reign of Gustavus (d. 1632), a Rhenish jug with the seal of the city of Amsterdam, dated 1630...and several 2¼-inch cannonballs, confirming Campanius in that the Susquehannocks were the only Native American tribe to employ artillery.

On display at the Washington Boro Society for Susquehanna River Heritage ( bluerockheritage.com ) is a case containing a stone pestle (top) used for grinding grain, a half-dozen stone axe heads, and a 2¼” cannonball thought to have been captured from Maryland during the 1643-44 expedition. All were found in the vicinity of Washington Boro. Photo by the author.

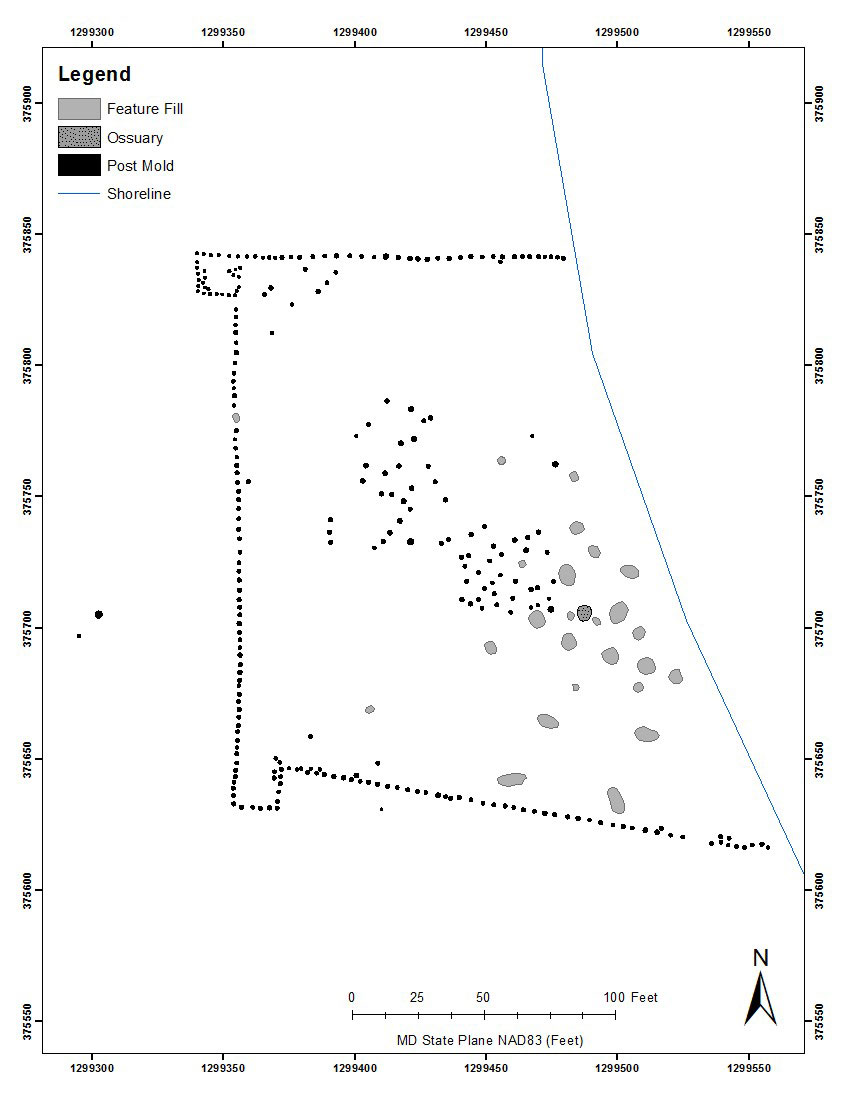

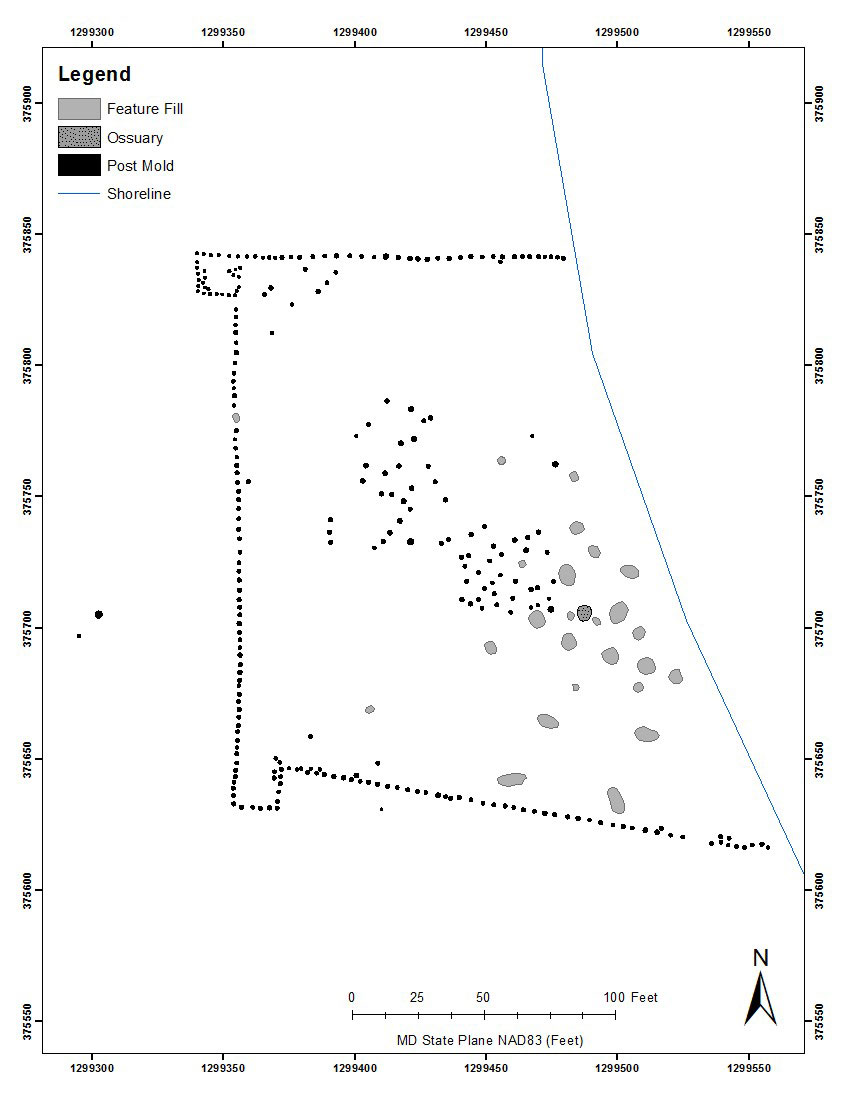

Around this time (1645) they established something of a tribal capital in what would be their most impressive village, Connadago. (The name may have simply been their word for “town.”) Located between Conestoga Creek and Washington Boro, the site is today bisected by a main road. The western side fronts on the Susquehanna and has been heavily eroded since the river rose behind the dam. The eastern side is an open field, probably continuously farmed since the 1740s, with a long history of grave digging and amateur archaeology yielding the richest trove of Indian artifacts and curios in the county. In 1968-69 much of this over-disturbed top layer was bulldozed off, allowing partial but deep-level, detailed examination of the site.

Google Earth view of site of Connadago (1645-1665) showing partial outline of (partly double-layer) stockade wall, bastions and position of some longhouses.

Find it

The area just to the north was previously occupied by the Shenks Ferry Culture, circa 1450–1550

What the excavation team found was well-nigh astounding. The marks of ancient postholes traced the outlines of Iroquois-style longhouses averaging 60 feet long, yielding a population estimate of up to 4500—about equal to all the French, Dutch and Swedes in North America put together. (Contemporary accounts confirm the Susquehannocks then numbered some 1300 warriors alone.) The town stockade enclosed over twelve acres, protected on the west by the river and on the east by two protruding, European-style bastions covering the approaches with enfilading crossfire, presumably by cannon.

The reason for their consolidation and fortification may not have been apparent to the bay-area English and Swedes, but the Susquehannocks must have seen trouble looming upriver. The Iroquois, Huron, French and Dutch had fought each other to a bloody stalemate that the Europeans were not numerous enough, and none of the native tribes strong enough, to tip. To gain the upper hand, each needed a powerful ally. For that, they all looked south. Down the Susquehanna.

“We have learned that you have enemies,” Susquehannock envoys told the Huron, “and you have only to say to us ‘Lift the axe’ and we assure you either they shall make peace or we shall make war upon them.”

The prospect of such an alliance alarmed not only the Five Nations, but their European partners. If the Iroquois went under, the Dutch would receive only those scraps of fur the French, Swedish and English declined. Their response was to arm the Five Nations with some 400 muskets.

“The 16th day of March in the present year, 1649, marked the beginning of our misfortunes,” a French Jesuit reported. “The Iroquois, enemies of the Hurons, to the number of about a thousand men, well furnished with weapons—and mostly with firearms, which they obtain from the Dutch, their allies—arrived by night at the frontier of this country.”

“War Chiefs” by Craig Mullins

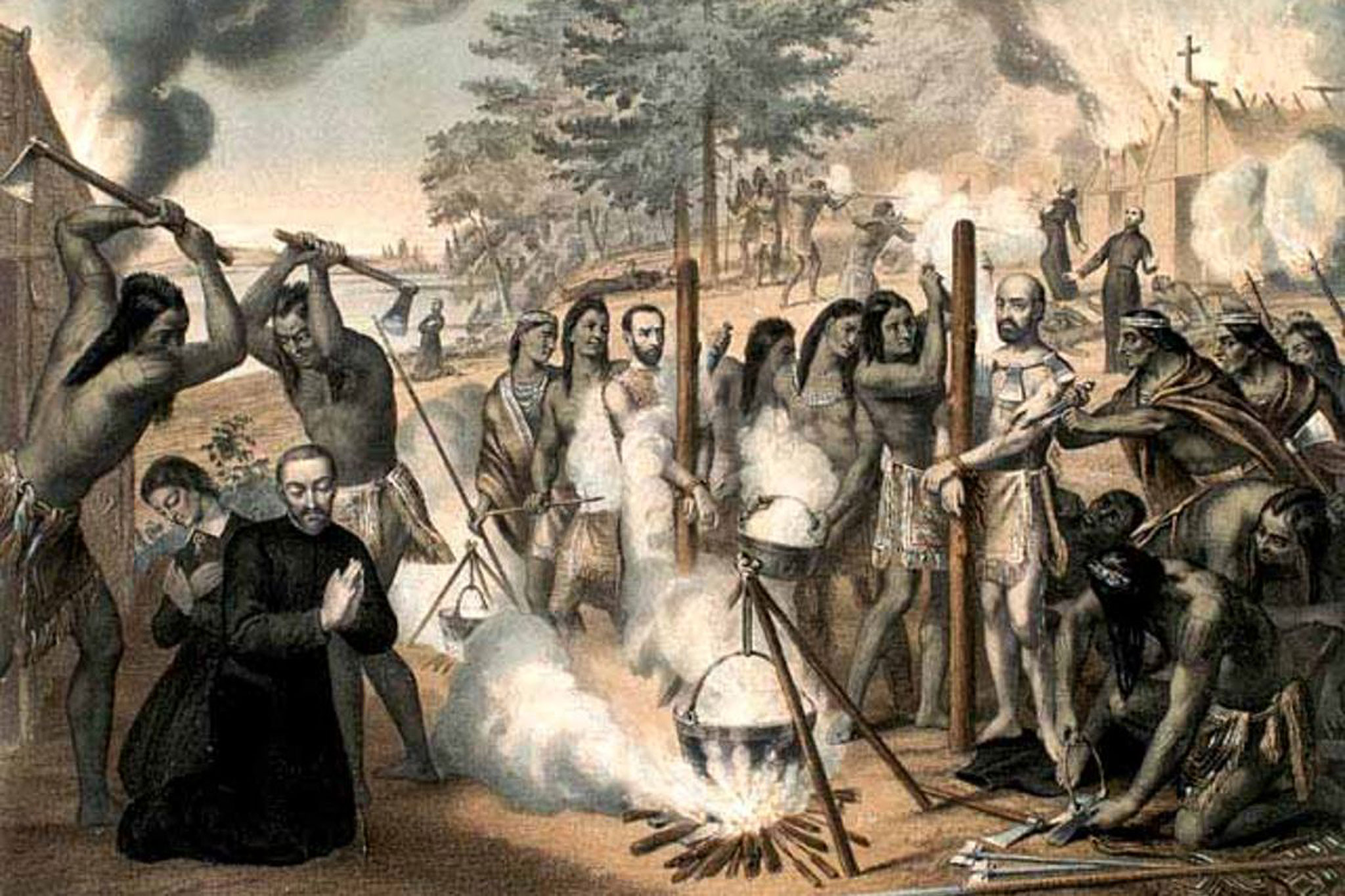

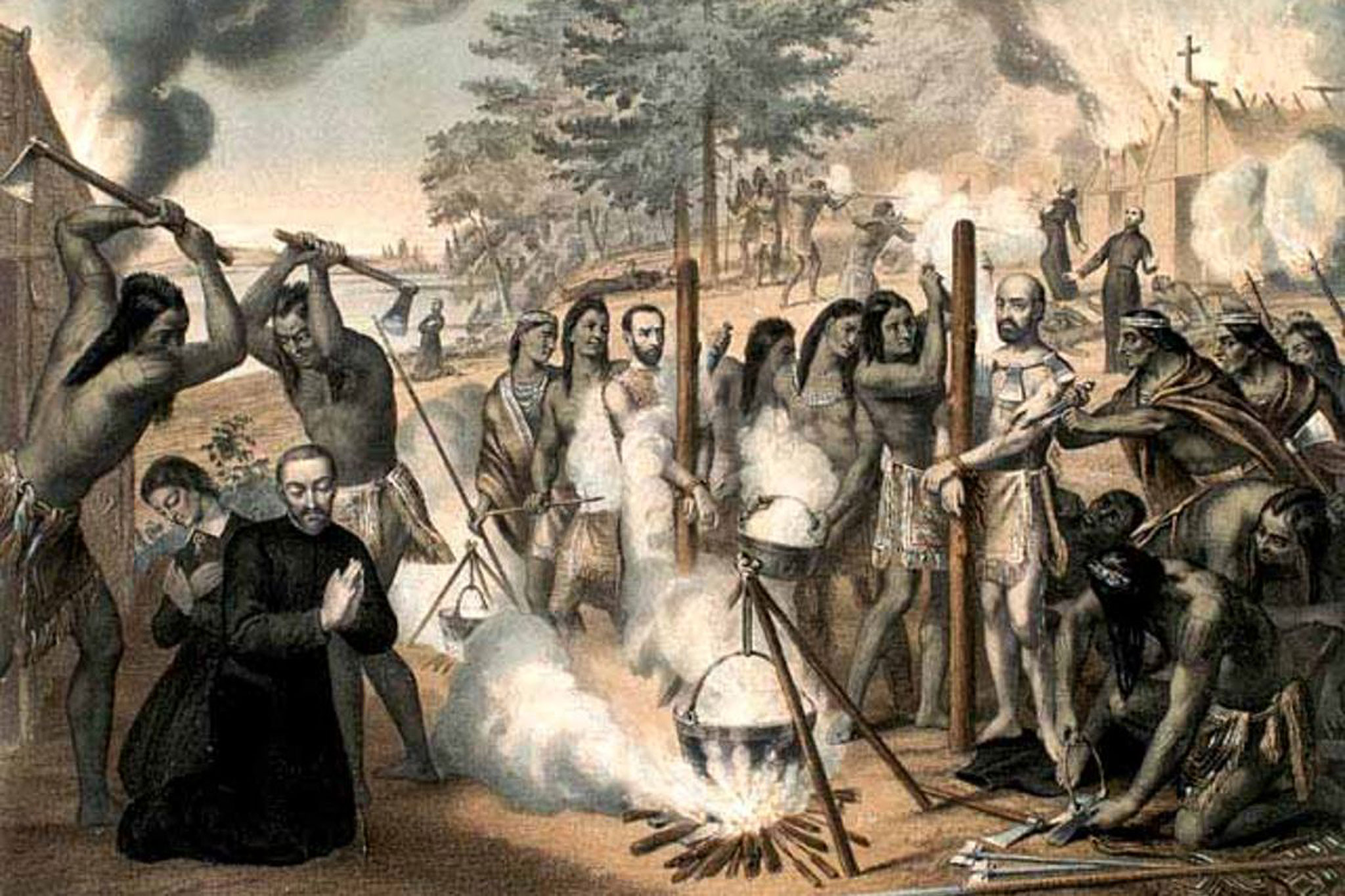

For a year the Five Nations rampaged across the north woods. Replenishing their own numbers with adopted prisoners, they put the rest to death by methods of immolation, flaying and dismemberment, as slow and diabolical as any medieval inquisitor could have devised. Jesuits in particular were singled out for martyrdom so brutal they must have believed the Iroquois to be the very minions of Satan.

March 1649: Mohawks martyr Jesuit missionaries Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lallemant. They were bound to stakes, scalped, then “baptized” with boiling water. For each, a “necklace” of hatchets was tied, thrown into the fire until red hot, then draped around their necks. They were said to have borne their suffering stoicly, and were canonized in 1930.

Surviving Huron abandoned their lands. Iroquois war parties prowled the shores of the Great Lakes, haunted the woods around Quebec and Montreal, and probed down the Susquehanna. For mutual self-defense, the Susquehannocks in July 1652 entered into an alliance with their former enemies, the English.

A Catholic foothold suffering a Puritan revolt of her own and not on the best terms even with Protestant Virginia, Maryland needed powerful native friends, and the Susquehannocks were wise to keep their options open. Overly bold considering their motherland was on the decline, the poorly supported Swedes took Ft. Casimir (modern New Castle, Del.) from New Netherland. In retaliation Dutch Director-General Peter Stuyvesant required only a token force to demand they hand over New Sweden. All of it. Permanently.

New Amsterdam, 1660

The Swedes acquiesced, but their native allies did not. Even before Stuyvesant returned to Manhattan the Susquehannocks amassed 600 warriors from allied tribes and landed a fleet of canoes on its southernmost point. Next time you’re downtown in the Big Apple, imagine those narrow streets running with painted, hatchet-waving, gun-shooting, screaming Susquehannocks, looting, burning and razing farms as far as modern Harlem, the Bronx and Jersey City. They committed few murders but took some 150 hostages, wishing not to expel or even alienate the Dutch, but merely teach them who held real power in the New World. For no more reason than this, they conquered New York City. Perhaps because they had no wish to keep it, the “Peach Tree War” was moot and is today largely forgotten, but—forced to abandon Staten Island to keep the rest—the Dutch (and all Europeans) were only just now realizing how badly they had underestimated this tribe.

Only the Iroquois Five Nations remained with any hope of reining in the Susquehannocks. In 1663 the Seneca led a combined force of 800 warriors downriver to lay siege to their capital, Connadago.

Woodland warfare. By 1663 the native tribes were well versed in gunpowder, and the Susquehannock fort even mounted cannons.

“But they saw that this village was protected on one side by the [Susquehanna],” the Jesuits learned afterward, “...and on the other by a double curtain of large trees [stockade], flanked by bastions, erected on the European manner and being supplied with some pieces of Artillery [captured from Maryland years earlier]. Surprised at finding defenses so well-planned, the Iroquois abandoned the projected assault.”

Instead they connived to slip some two-dozen men inside under guise of parley. The Susquehannocks were not fooled. The emissaries were “immediately seized, and without further delay made to mount on scaffolds where, in sight of their own army, they were burned alive.”

James, Duke of York, the Lord High Admiral of England (future James II)

At the sight the Iroquois lost heart and went home. They had not yet even reached their low point. In 1664 England’s Charles II ordered his brother James, Lord High Admiral, Duke of York and future James II, to do what the Susquehannocks had not bothered to: take—and keep—New Amsterdam. This he did with four ships and nary a shot fired.

For the first time the Atlantic coast from Maine to the Carolinas was English, but the English weren’t necessarily all on the same side. One might expect Catholic James to ally his colony to Catholic Maryland, but to keep the Iroquois from going over to the French (now allied with Holland), New York continued to supply them guns, even as Maryland declared war on them in support of the Susquehannocks.

George Alsop, 1666

In these years of Susquehannock supremacy, indentured servant George Alsop was working off a four-year term in Maryland. Upon his return to England in 1666 he wrote of the tribe in his travelogue, A Character of the Province of Maryland, as “a people lookt upon by the Christian Inhabitants as the most Noble and Heroick Nation of Indians that dwell upon the continent of America.

“...the Men think it below the honour of a Masculine, to stoop to any thing but that which their Gun, or Bow and Arrows can command....

“...They are very constant in their Wives; and let this be spoken to their Heathenish praise...there would be as amiable beauties amongst them, as any Alexandria could afford, when Mark Anthony and Cleopatra dwelt there together.”

A good Christian, Alsop took exception to any god but his own, noting the Susquehannocks revered “...no other Deity than the Devil,” and believed “that the World had a Maker, but where he is that made it, or whether he be living to this day, they know not.” And as for their government, “All that ever I could observe in them as to this matter is, that he that is most cruelly Valorous, is accounted the most Noble...he that fights best carries it here.”

Under chiefs Harignera (Civility) and the much-feared Hochitagete (Barefoot), the tribe moved across the river, just west of their previous villages. Twenty years of warfare and disease had thinned their warrior strength to just 300, though no less formidable. In 1671 a party of sixty Seneca and Cayuga warriors were surprised and routed by an equal number of Susquehannocks—even though, according to the Jesuits, none of the latter were over the age of 16.

In a twist of the ongoing European wars, in 1673 the Dutch retook New York, only to meekly sign it back over to the English little over a year later. Perhaps it’s only coincidence that in those same months the Five Nations experienced a resurgence, and the Susquehannocks near-total defeat.

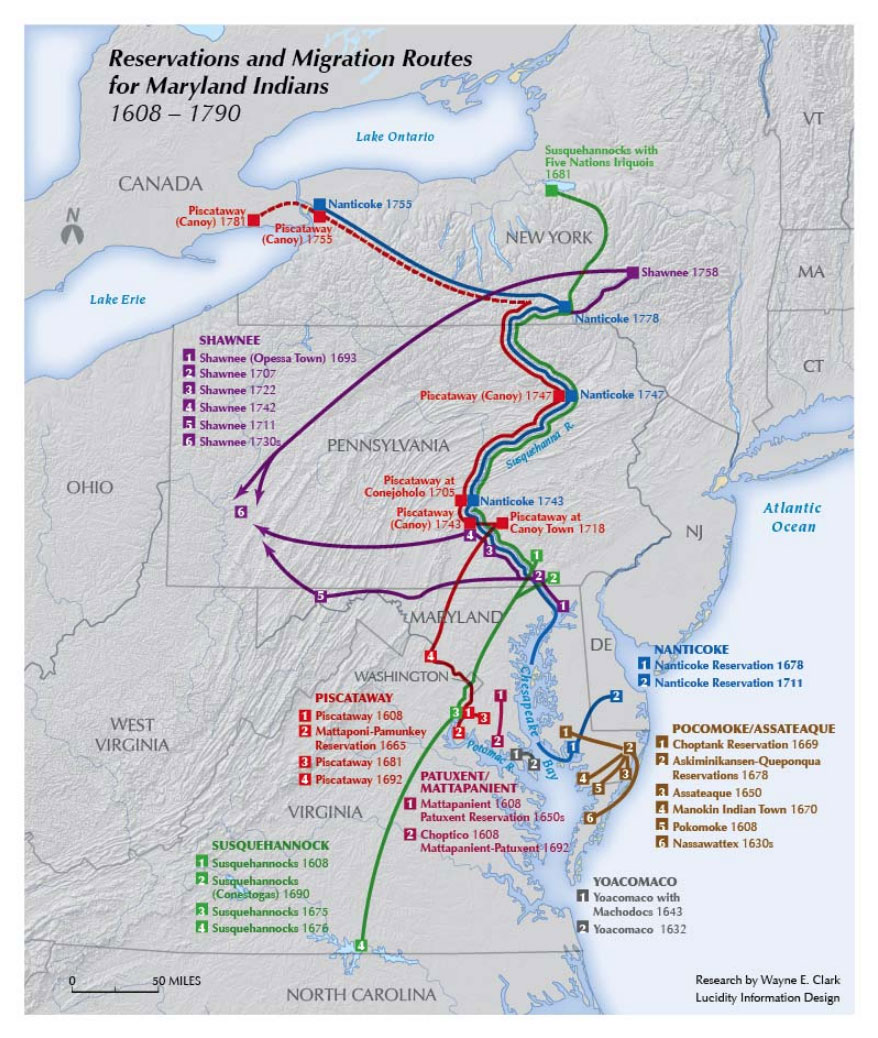

The decisive move of the generations-long war proved anticlimactic. The details are lost to history. Later the Iroquois boasted of a great triumph, but colonial archives make no mention of battle. One theory claims that political machinations between Maryland and New York resulted in a betrayal. King Phillip’s War was heating up in New England; New York desired peace with the Five Nations more than Maryland required it with the Susquehannocks. Most crucially, lacking Dutch support, the Iroquois could and did turn to their old enemies, the French, for powder and firearms. The Susquehannocks, on the other hand, were now totally dependent on the English. (Early tribal gravesites east of the river usually include the deceased’s guns, but not later ones on the west bank; firearms may have become too few and precious for posterity.) When Maryland abruptly made peace with the Seneca and declared war on the Susquehannocks, they were utterly cut off. Forced to abandon their river and beg sanctuary, Harignera and his people were permitted to move south, onto old Piscataway tribal lands at Moyaone (modern Accokeek Creek Site at Mockley Point) on the Potomac River.

This solution pleased no one. Iroquois ran unopposed raids downriver into Chesapeake Bay, for which Susquehannocks were blamed. Thefts escalated into murders, and then massacres, on both sides of the Potomac. In September 1675 Virginia sent 1,000 men under Col. John Washington (great-great grandfather of the future president) to join a Maryland expedition under Maj. Thomas Truman against the Susquehannocks.

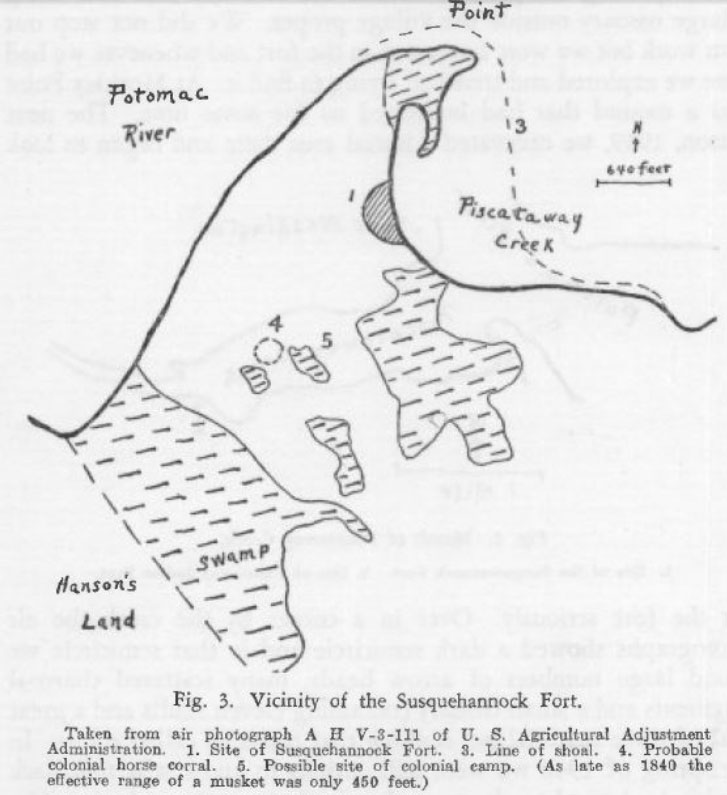

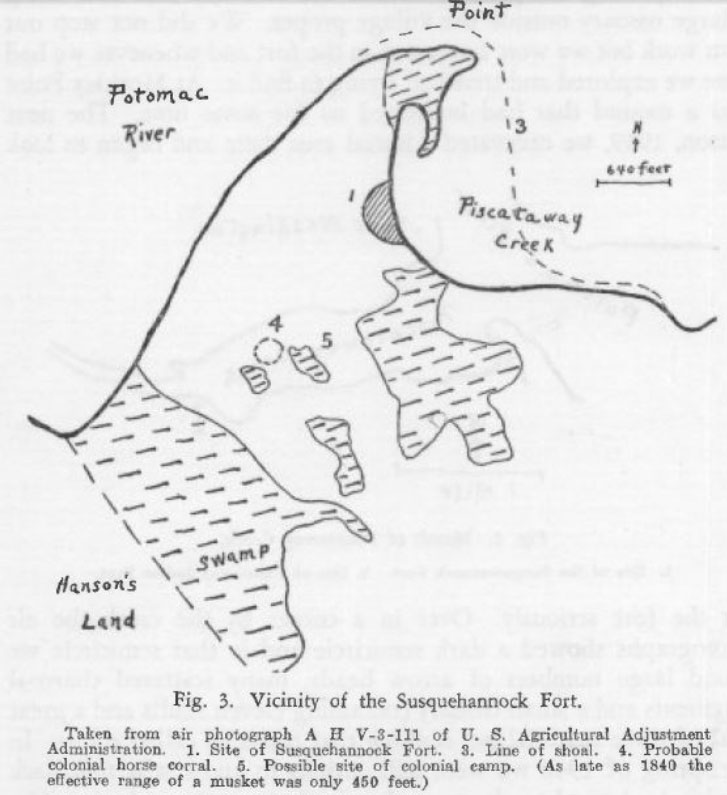

Mockley Point on Piscataway Creek, MD., 1675

Find it

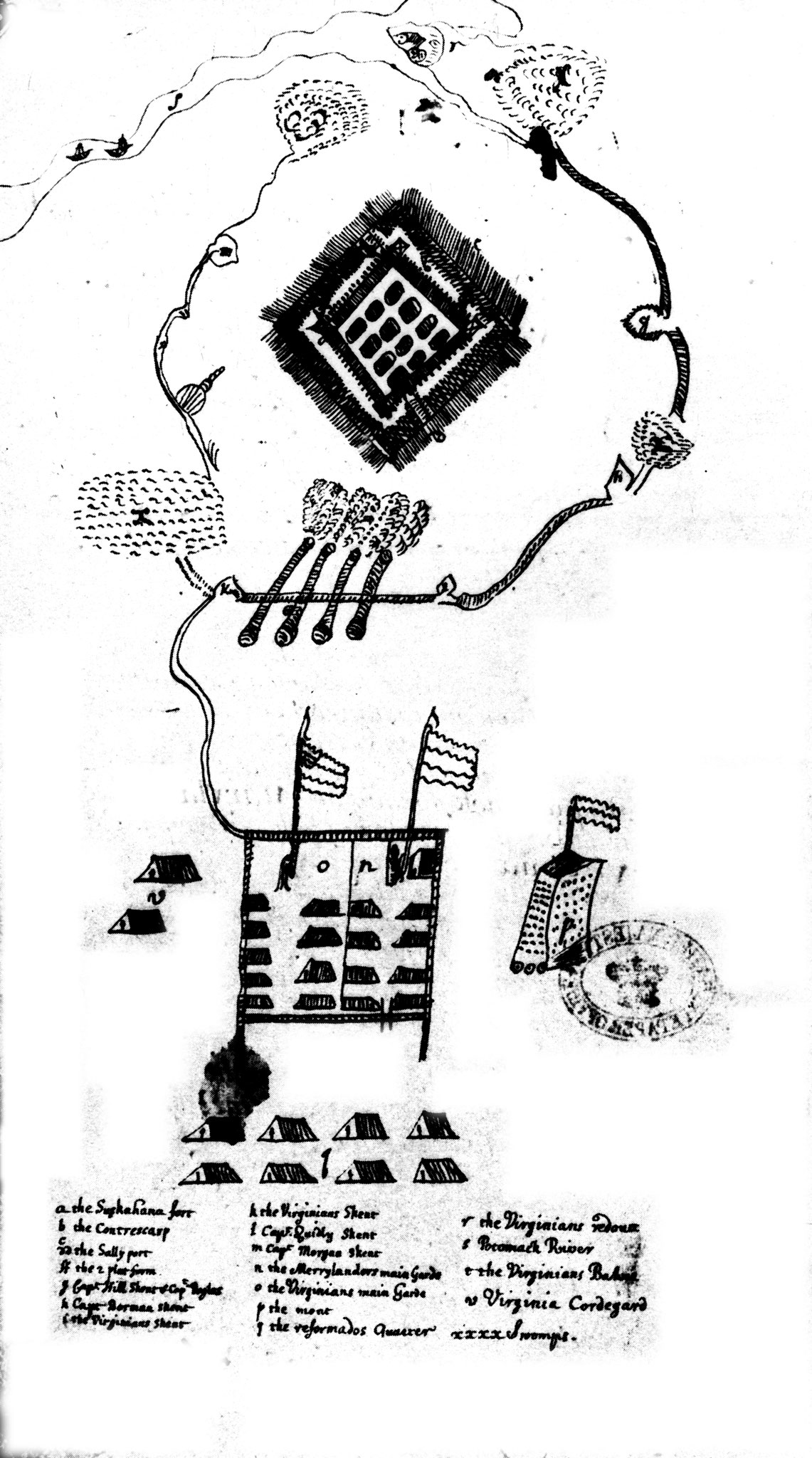

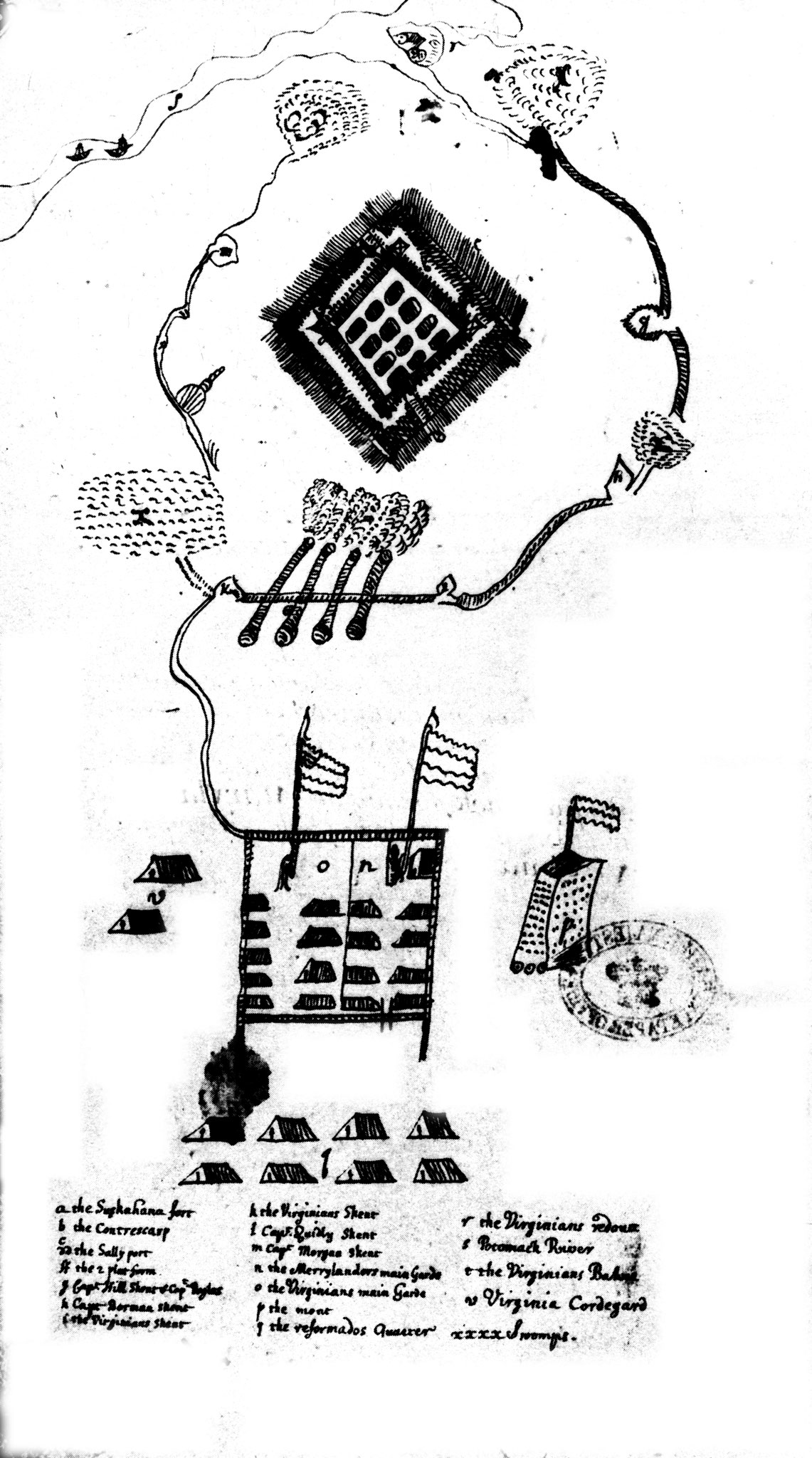

Period map of Mockley Point, Accokeek, MD, during the seige of 1675. Susquehanna Fort at top. Combined Virginia/Maryland camp at bottom. Not to scale: the little winding creek in upper left represents the Potomac River. From the British Record Office,

London

Down to less than 100 warriors, perhaps 250 people total, the tribe had nevertheless fashioned for themselves an impregnable citadel, with a moat and stockade of half-foot-thick trees. With no artillery to blow down the walls and no sappers able to undermine them in the swampy riverine soil, the English were forced to parley. Unlike the Iroquois sending envoys in, they required Harignera to come out. He had since died, but a handful of chiefs emerged to protest their tribe’s innocence, lay blame for the recent outrages on the Seneca, and even offer guides to aid in their pursuit. They went so far as to bring out the old safe-conduct medal with the black and yellow ribbon, presented to them by Maryland some three decades earlier, which they’d held in honor all the while.

These weren’t the same Marylanders. The chiefs were taken into custody. Somehow (afterward no one seemed to recall how it happened or who did it) all but one was clubbed or tomahawked to death.

Excavations at the Susquehannock fort at at Mockley Point on Piscataway Creek, MD., 1939–1940

More

Now it was war. The colonials laid siege, though poorly. Warriors sallied out to provision the fort with stolen English horses, but after six weeks food still ran low. (Some 42 graves have been found within the grounds, though perhaps not all Susquehannock.) Ultimately, in the middle of the night, the survivors—men, women and children—simply opened the gate and walked out, right through the enemy encirclement, pausing only to kill ten English as they slept.

Major Truman was briefly imprisoned for this debacle, particularly the Susquehannock chiefs’ “Most Execrable of Murthers, [sic]” but ultimately acquitted and released. Col. Washington, a member of the Virginia Assembly, not only went unpunished, but that same year received ownership of high ground across the Potomac from Piscataway, which his descendants eventually named Mount Vernon. Today Mockley Point—a muddy tongue of cattail swamp and vine-tangled sweet gums—is part of Piscataway National Park, not because Susquehannocks died there but because Congress decreed that bank of the Potomac should ever appear as George Washington saw it from his back porch. A dilapidated outhouse is all that stands in the vicinity of where chiefs were slain.

Mockley Point, Piscataway Park, MD, looking roughly west. A lonely dilapidated outhouse stands where Susquehannock chiefs died by treachery.

Nathaniel Bacon

Whether or not previously innocent of raiding, the Susquehannocks now ran wild up and down the James, York and Rappahannock rivers, burning tobacco stores and slaughtering up to a hundred colonists for each of their lost chieftains. Virginia planter Nathaniel Bacon raised up a militia and inflicted heavy retaliatory casualties on every local tribe except the Susquehannocks, whom he couldn’t catch. When even the Jamestown government opposed him, he marched with 500 men on the capital as well, and torched it. Though it sputtered out quickly when its leader died of dysentery in 1676, Bacon’s Rebellion has been called the “First American Revolution.” Its instigators, the Susquehannocks, are usually left out of the story.

Having made their point, the remnant of the tribe sought, and was granted, tentative peace by Maryland, Virginia, New York and Iroquois alike. Encouraged by New York Gov. Edmund Andros and the Five Nations (whose subjects they became), they moved back up the west bank of the Susquehanna to build a new fort on almost the same site as that which they had abandoned earlier. It does not seem to have been a happy place. They resided there only four or five years, but left behind some 200 graves.

The survivors scattered among the Seneca in New York and Ohio, the Lenape, and the Shawnee and Conoy who had moved into the lower Susquehanna Valley. Interbred, they re-emerged around the turn of the century under a new name: Conestoga. Ringing of “Connadago,” the French/Huron Andaste, Andastogue, or Gandastogue, and even the Iroquoian kanata (town, from which “Canada”), “Conestoga” may near what the Susquehannocks actually called themselves all along. It seems to translate to “place of the immersed pole” or possibly “immersed rafters.” Anyone who’s lived on a Susquehanna flood plain can easily relate.

Conestoga Town was sited well inland from the river, as though the inhabitants wished no notice. Rather than old-fashioned longhouses, they lived in European-style cabins. In its heyday the town was probably home to about 200 total, but soon outgrew them in importance.

Penn’s Treaty with the Indians, by Benjamin West

West of Philadelphia, north of Baltimore, Conestoga became a crossroad of the Colonies—a layover stop, meeting place, and trade center for natives travelling the river, and thus for Europeans dealing with them. It was there that William Penn in 1701 (the year the French made peace with the Iroquois) signed his treaty with the Conestogas for the “lands, which are or formerly were the Right of the People or Nation called the Susquehannagh Indians.” (And yes, the Conestoga Wagon of Oregon Trail fame originated in the vicinity and carried the name west.) Meanwhile Wright’s Ferry, founded just to the north in 1730, grew into a relative metropolis (modern Columbia), eventually becoming George Washington’s personal choice for capital of the United States. Due to a miscalculation as to the exact location of the 40th Parallel marking the colonial border, everything south (technically including Philadelphia itself) fell under Maryland’s sway.

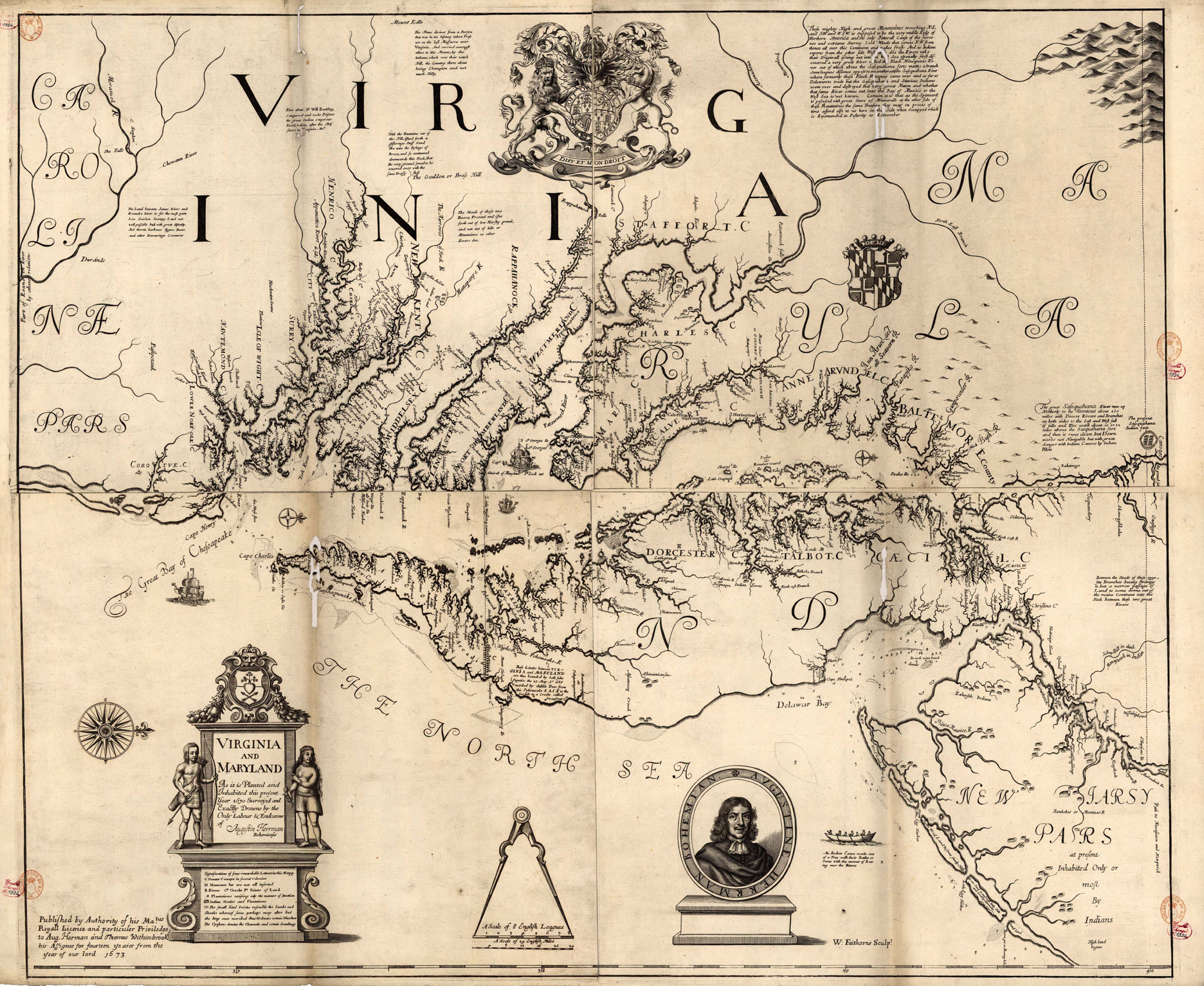

The Susquehannock Indian fort, long since abandoned, appears on Herman Moll’s map of 1729

The ruin of the last Susquehannock fort on the river’s west bank, almost on the disputed line, became a focus of contention and even a brief shooting war between the heirs of Lords Penn and Baltimore, unresolved except by royal decree in 1738 (and the Mason-Dixon Line in 1767). Watching gun battles from the safety of their little hamlet across the river, the former kings of the Susquehanna must have felt they had the last laugh.

The frontier had moved west. Furbearers were trapped out. The Conestogas lived as Europeans, under the protection of Penn and his descendants, taking no part in the French and Indian War. Numerous tribes who did (including remnants of the Huron, Lenape, and Shawnee) found themselves cut off by the French defeat. Rather than suffer English rule, they rose up. Pontiac’s Rebellion took eight English forts, including three (Presque Isle, Le Boeuf, and Venango) on the Pennsylvania frontier. Word of massacres and atrocities reached the Susquehanna. Thus it was that the Paxton Rangers militia, finding little success raiding upriver into the Wyoming Valley, turned vigilante.

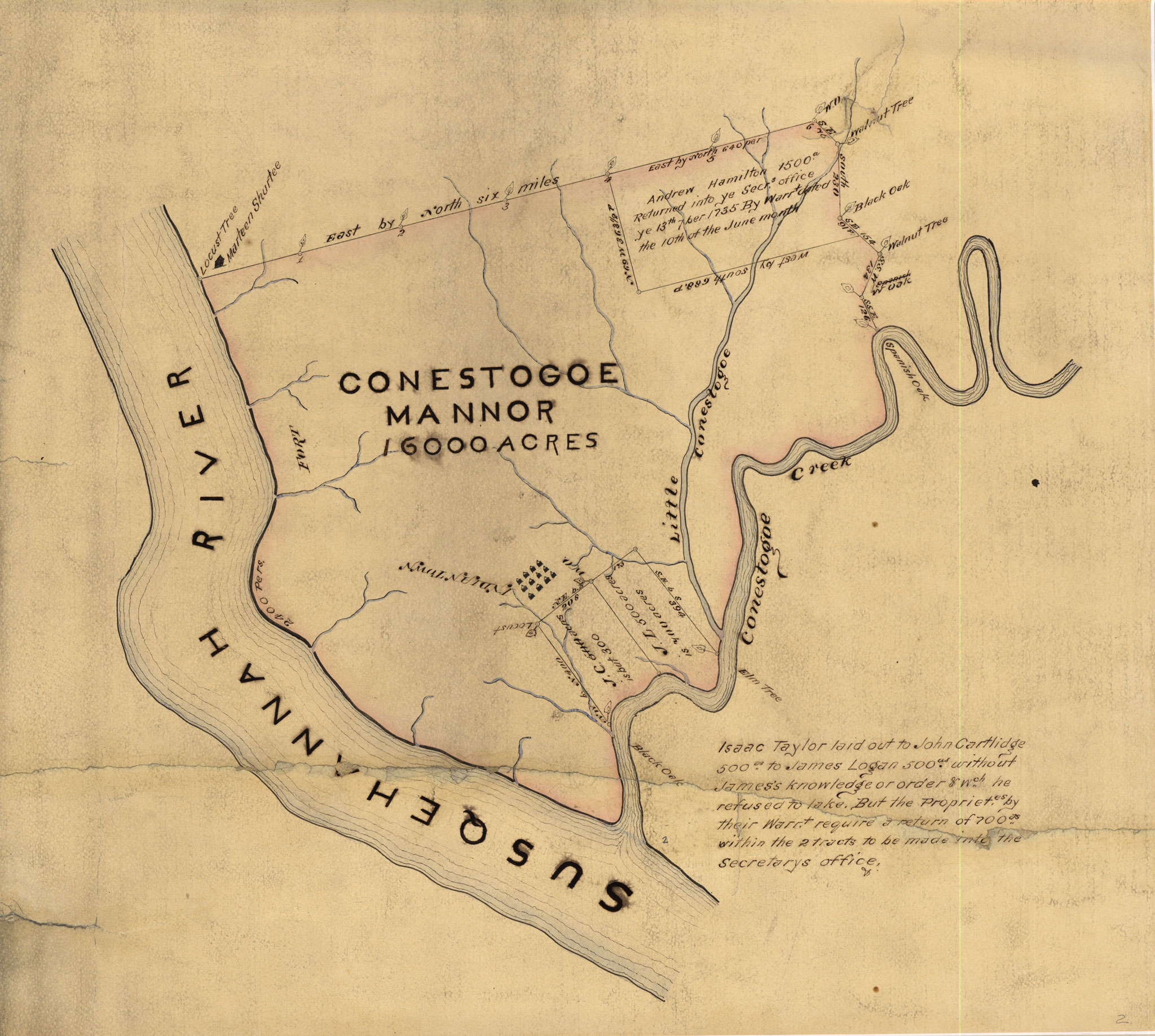

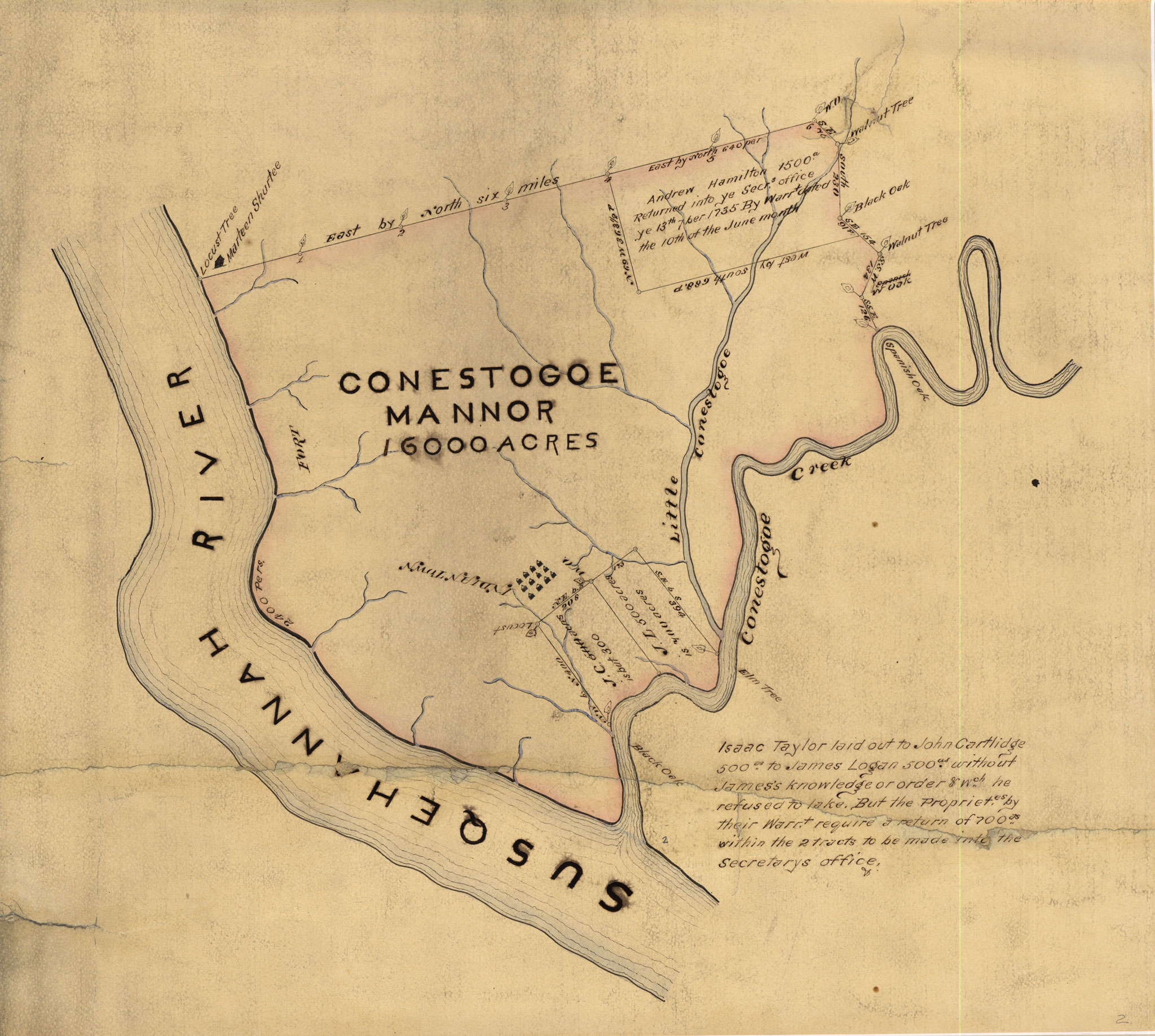

1764 map of Conestoga land shows their village near the center of 16,000 acres. By the time this map was made, the village was destroyed.

Conestoga patriarch Sohais or Sheehays, so old that he was said to have been present at the signing of the 1701 treaty, was a friend of the Penn government. However, two of his people, brothers Wa-a-shen and Tenseedaagua, known as George and Will Sauk or Sock, had been accused of sympathy for the rebel tribes, despite Will having served as translator and courier for the British during the war. George and Sheehays were both slain at Conestoga, but Will Sock led the last of the tribe to safety—or imprisonment—in the Lancaster workhouse. Among their possessions was a signed copy of the 1701 treaty. In it Penn had pledged that English and Indian would “forever hereafter be as one Head & One Heart, & live in true Friendship & Amity as one People.”

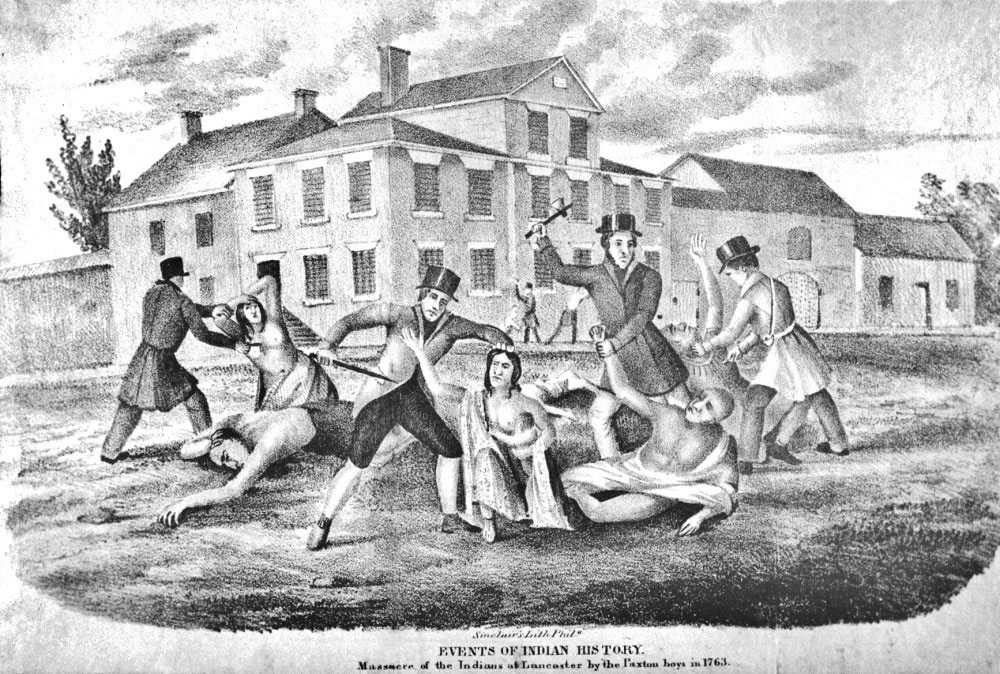

Safe in the big city, Philadelphians were outraged by the Conestoga Massacre, but many Lancastrians sympathized with the Rangers. On Tuesday, December 27th 1763, most were in church celebrating the third day of Christmas when up to a hundred Paxton Boys rode into town unopposed and broke into the workhouse.

Chasing their victims around the prison yard, they hacked to death Will Sock and his wife, Kaniaguas (Sheehays’ daughter, called Molly), sparing neither their children nor any of the rest. They tomahawked off hands and feet for trophies or dismemberment in the afterlife, scalped the bodies, mounted up and rode off. In all the slaughter took some twelve minutes.

This artwork, done decades after the fact, gets the costumes wrong, but the Lancaster workhouse in the background is largely correct.

Even Benjamin Franklin decried the Paxton Boys as “white savages.” Like Nathaniel Bacon before them, they marched on the capital, but refrained from burning the city. Though their identities were surely well known by many, none were ever positively named, let alone brought to justice.

Plaque to the left of the double doors in the lower rear of Lancaster’s

Fulton Opera House says it all. The workhouse yard where much of the killing was done was to the left. Photos by the author.

Find it

The only surviving Conestogas were a couple who, as servants in a colonial household, had lived elsewhere for years. They died childless. Today, though many Americans and even Europeans claim Susquehannock blood, the tribe is extinct. The workhouse in Lancaster is the basement of an opera house. Conestoga Town is vacant farmland. A few decades ago archaeologists uncovered entire native burials around the area, but the verdant Susquehanna Valley has lately become so heavily fertilized (with runoff often cited as a cause of Chesapeake Bay dead zones) that skeletons are now often found dissolved down to their teeth caps.

Their tale is that of Native America, writ in extremes. Victors over Dutch, Iroquois and English alike; artillerists, fortifications experts, never decisively defeated—then betrayed, vanquished, and vanished—few tribes rose so high, or fell so far, as the Susquehannocks.

Bibliography

Acrelius, Israel, and William Morton Reynolds. A History of New Sweden: Or, The Settlements on the River Delaware. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1874. http://books.google.com/books?id=IEjjAAAAMAAJ

Brubaker, John H. Massacre of the Conestogas: on the Trail of the Paxton Boys in Lancaster County. Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010. ISBN 9781609490614

de Vries, David Pierterzon. Voyages from Holland to America, A.D. 1632 to 1644. Trans. Henry Cruse Murphy. http://books.google.com/books?id=2MJPAAAAcAAJ

Donehoo, Dr. George P. A History of the Indian Villages and Place Names in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, PA: The Telegraph Press, 1928

Eshleman, H. Frank. Lancaster County Indians: Annals Of The Susquehannocks And Other Indian Tribes Of The Susquehanna Territory. (1909) Whitefish, MT: Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2007. ISBN 0548640343

http://books.google.com/books?id=4gUTAAAAYAAJ

Holm, Thomas Campanius. A Vocabulary of Susquehannock. Trans. Peter Stephen Duponceau. Merchantville, NJ: Evolution Publishing, 2007. ISBN 9781889758855

Holm, Thomas Campanius. Description of the province of New Sweden: Now called, by the English, Pennsylvania, in America. Trans. Peter Stephen Duponceau. Philadelphia, McCarty & Davis, 1834.

http://books.google.com/books?id=GgANAAAAYAAJ or http://www.archive.org/stream/descriptionprov00poncgoog/descriptionprov00poncgoog_djvu.txt

Kellock, Katharine A. Colonial Piscataway in Maryland. Accokeek, MD: Alice Ferguson Foundation, 1962.

Kent, Barry C. Susquehanna’s Indians. Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1984. ISBN 0892710241

Jennings, Francis. “Glory, Death, and Transfiguration: The Susquehannock Indians in the Seventeenth Century.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 112.1 (1968)

http://books.google.com/books?id=OVkLAAAAIAAJ

“Relation of Captain Thomas Yong, 1634.” Narratives of Early Pennsylvania, West New Jersey, and Delaware, 1630-1707. Ed. Albert Cook Myers. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1912.

http://books.google.com/books?id=HNMLAAAAYAAJ

Wallace, Paul A. W. Indians in Pennsylvania. Illus. William Rohrback. Harrisburg, Pa.: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1981.

More from Don Hollway:

.jpg)