BAT OUT OF HELL

The Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet rocket interceptor outperformed every WWII combat plane...if its pilots lived to fight

|

by DON HOLLWAY

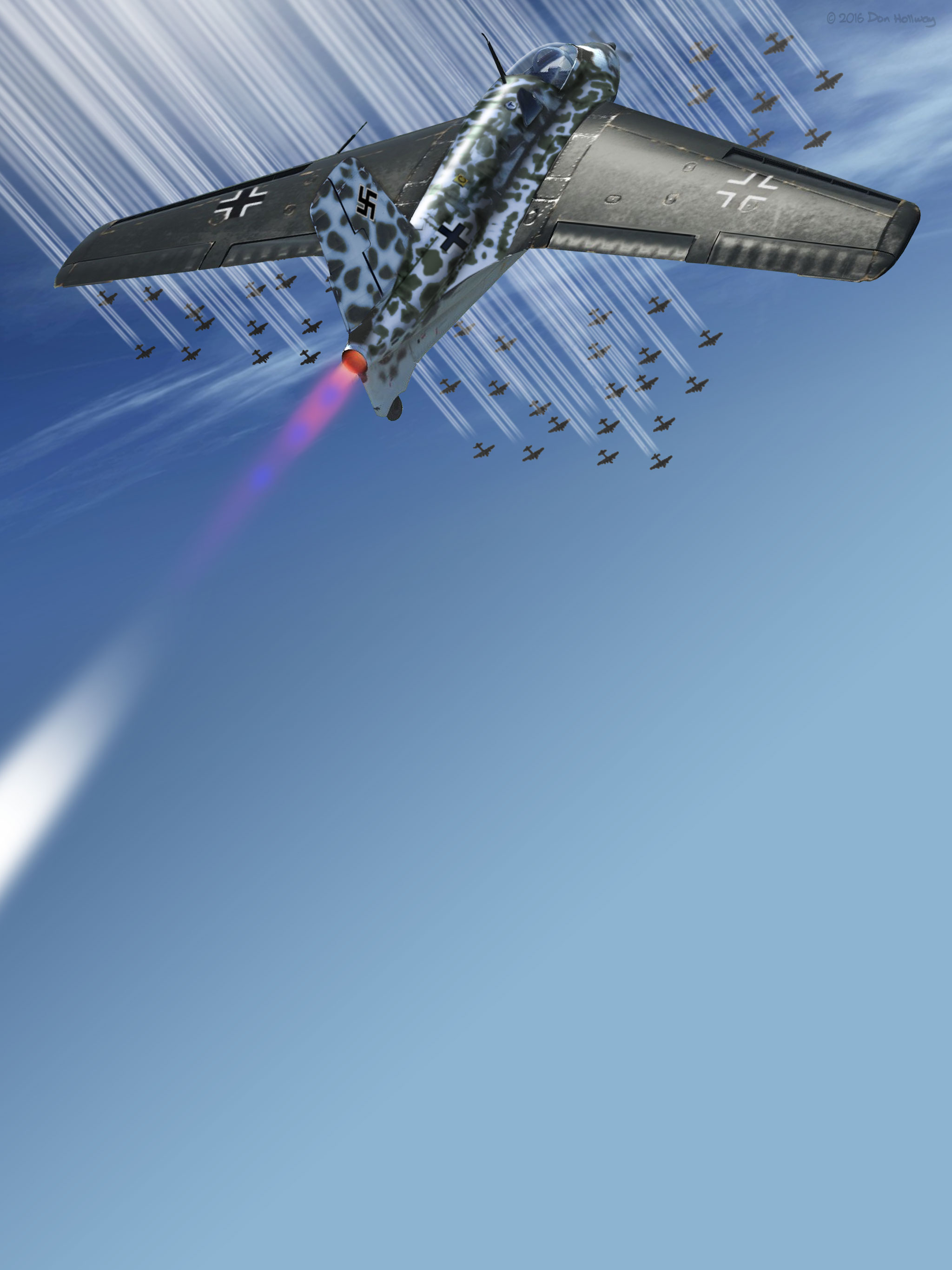

In late July 1944, Mustang pilots claiming air superiority over Germany got a nasty shock. Col. Avelin P. Tacon Jr. of the 359th Fighter Group reported, “My eight ship section was furnishing close support to a Combat Wing of B-17s that had just bombed Merseburg. The bombers were heading south at 24,000 feet and we were flying parallel to them about 1,000 yards to the east at 25,000 feet. Someone called in contrails high at six o’clock.” Already more than a mile above Tacon’s Mustangs, two stubby, tailless, swept-wing single-seaters dived to the attack. “When they were still about 3,000 yards from the bombers they saw us and made a slight turn to the left into us, and away from the bombers,” Avelin recalled. “Their bank was about 80 degrees in this turn, but they only changed course about 20 degrees....Their rate of roll appeared to be excellent, but radius of turn very large. I estimate, conservatively, they were doing between 500 and 600mph.” The intruders slashed past the American formation. One dived away and the other climbed into the sun, as another 359th pilot put it, “like a bat out of hell.” That quickly, they were gone. “Although I had seen them start their dive and watched them throughout their attack,” Tacon admitted, “I had no time to get my sights anywhere near them.”

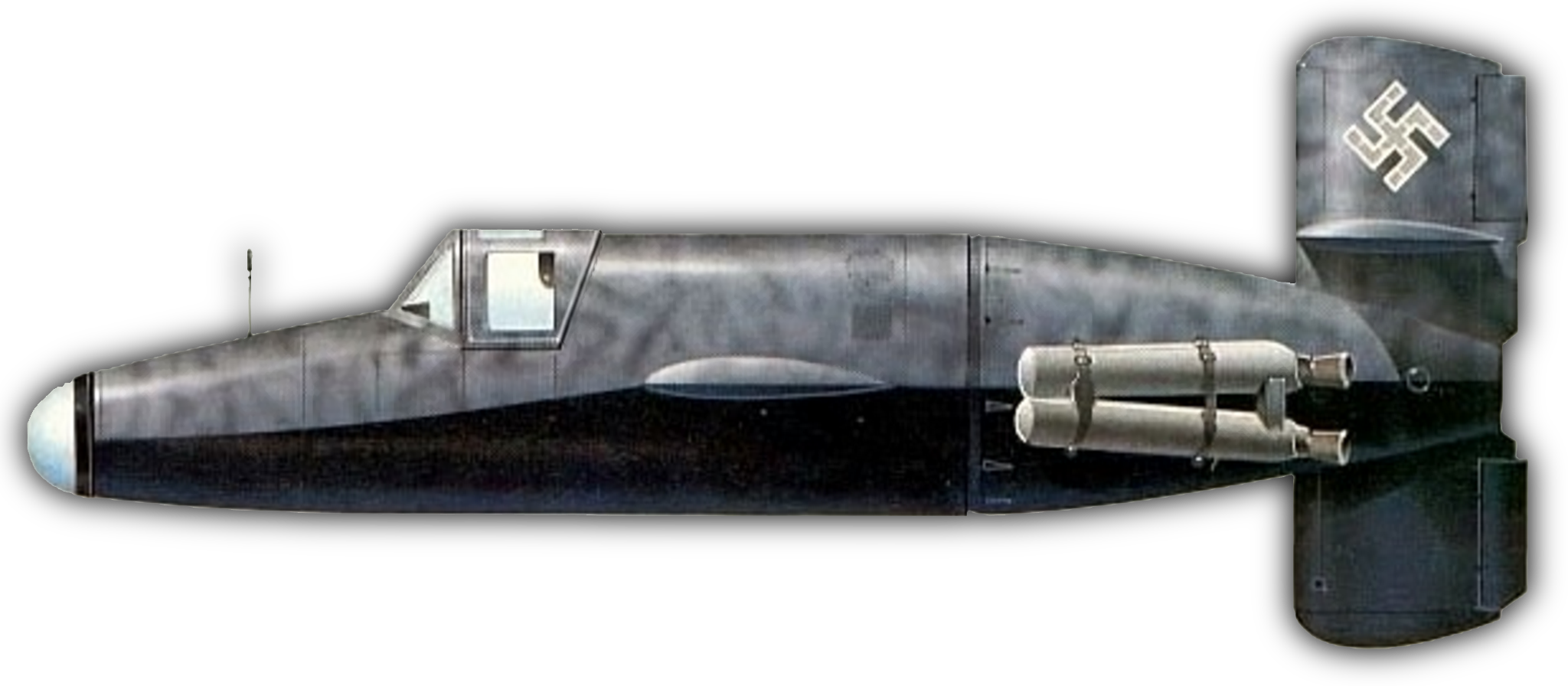

Messerschmitt Me 163B 1a Komet by Shigeo Koike 1944 was the year of the Wunderwaffen, German wonder weapons. King Tiger tanks. Jet fighters. Helicopters. Guided missiles. Cruise missiles. Prototype ICBMs. Railway guns. Long range superguns. Spurred by the specter of imminent defeat, projects that had been years in development were suddenly given highest priority, accelerated into production, and put into service. Having evolved since the 1920s, the rocket fighter would prove one of the more successful ventures. Whether it proved combat-worthy would be another matter....

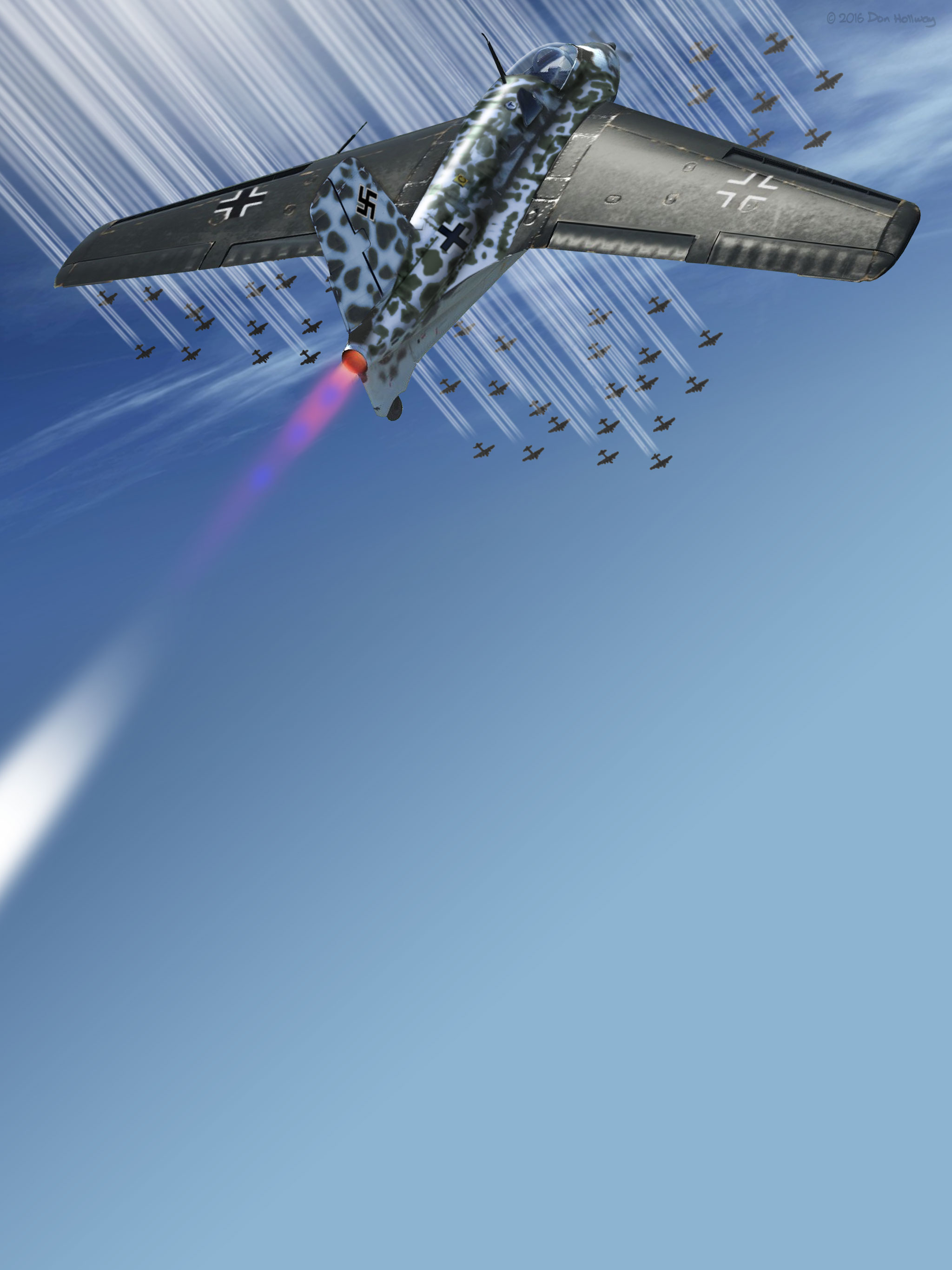

First rocket-powered flight: 11th June 1928 Fritz Stamer in the Lippisch Ente (Duck). It was powered 8.8 pound sticks of black powder, ignited sequentially from the cockpit, each delivering 30 seconds of thrust. The first attempt failed when one of the rockets burned out. On his second attempt, shown here (launched with a bungee cord), Stamer flew about .9 mile around the Wasserkuppe, the highest peak in the Rhön Mountains. The flight lasted only about 80 seconds. On a third attempt, one rocket exploded and the Duck caught fire 65 feet in the air. Stamer put it down and jumped out unharmed, but the Ente burned to the ground. It was the Allies themselves who forced the Germans into thinking outside the box. The Versailles Treaty ending WWI, which forbade Germany powered single-seat aircraft (i.e., fighter planes), forced its scientists, engineers and pilots into gliders and rocketry. The Wasserkuppe, the highest peak in the Rhön Mountains, served as proving ground for self-taught aerodynamicist Alexander Lippisch’s innovative flying-wing gliders. Carmaker Fritz von Opel, who liked rocket-powered cars for publicity stunts, bought Lippisch’s “Ente” (Duck) sailplane and equipped it with black powder rockets. On June 11, 1928, just 25 years after the Wright brothers proved powered manned flight was even possible—and 11 years before jet propulsion became a reality—flight instructor Fritz Stamer flew the rocket plane nearly a mile around the Wasserkuppe. On his next attempt, however, one of the fuel sticks exploded. “The four kilograms of black powder flew out and immediately caught the plane on fire,” Stamer remembered. He put down and got out alive, but the Duck was a total loss. When the German military reasserted itself, it looked into liquid-fuel rockets that could be shut off and re-lit. Wernher von Braun favored burning methyl alcohol with liquid oxygen, then in short supply. Engineer Hellmuth Walter preferred less volatile, more plentiful hydrogen peroxide—not the dilute H₂O₂ available at the corner drugstore, which fizzes when sterilizing a scratch, but 80%-pure “T-Stoff.” Reacting with “Z-Stoff,” a catalyst of calcium or potassium permanganates mixed in water, it decomposed near-explosively into high-pressure steam at 800° C. It also spontaneously ignited any organic material it touched, and dissolved human flesh. “If you stick your finger in it,” Lippisch warned, “then you get only the bone out.” Von Braun’s idea for a vertical-takeoff fighter was rejected. Ernst Heinkel’s tiny He-176 prototype used Walter’s rocket, but could provide only 40 seconds of thrust; Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring dismissed it as a “nice little toy.” Prior to war, no pressing need was foreseen for a rocket fighter. Development slowed. Come the summer of 1941 it was a different story. “Papa” Lippisch, by then working at Messerschmitt, installed a Walter rocket in his “Project X” : a tailless delta airplane, the Me-163A.

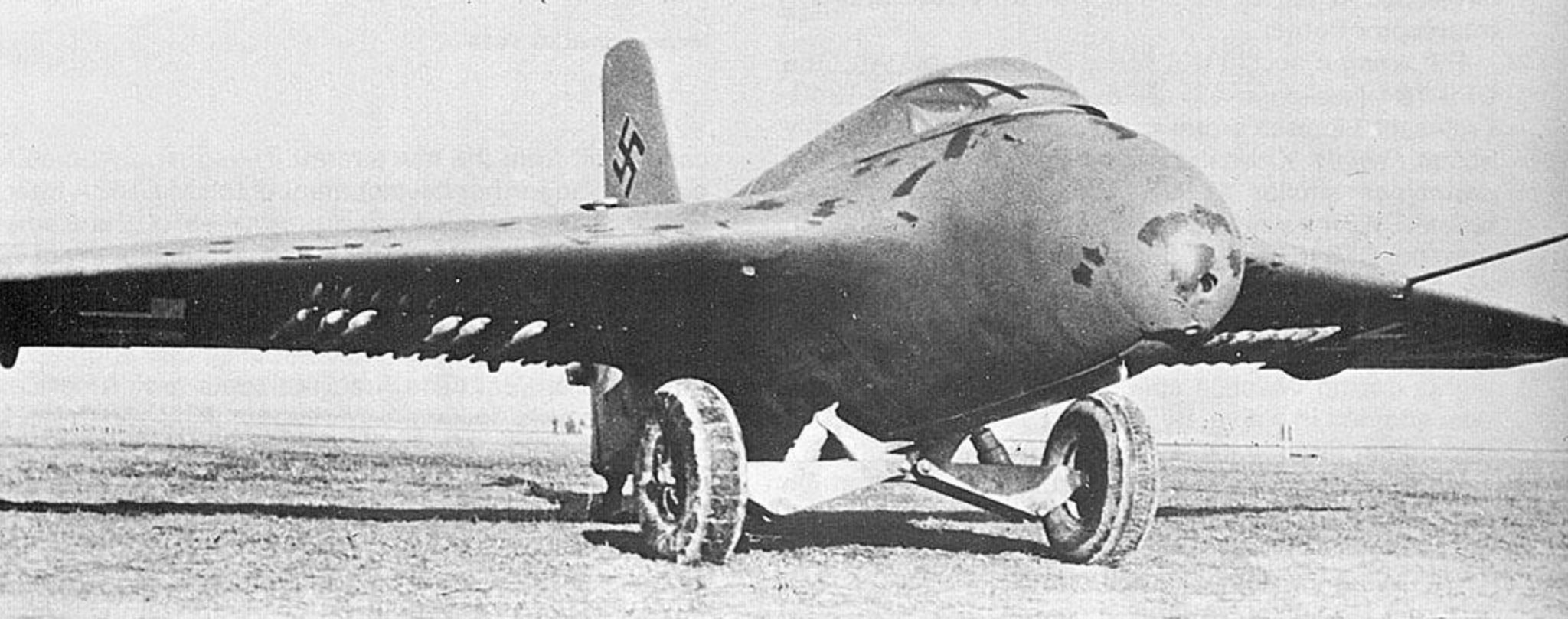

Me-163A V3. On October 3, 1941, test pilot Heinrich “Heini” Dittmar flew this prototype to a new speed record of over 1000km/h Me-163A testing (Silent) Even though it burned most of its fuel just taking off, the 163A—“Anton”—climbed at 4,000 meters per minute and easily broke all existing speed records. On October 2nd, 1941, Lippisch’s favorite glider pilot, Heinrich “Heini” Dittmar, had an Me-110 tow him up over 13,000 feet with a full fuel load, cast off, and hit 1,003.67kph (629mph, about Mach .84) in level flight. “And then, things started to happen,” Dittmar recalled. “...The airplane was being pushed down by an incredible force. It took everything I had just to keep my hand on the stick. Some junk floated up from the floor of the cockpit, passed my face and stuck to the canopy....The engine quit!” Compression shockwaves had caused airflow over the wing to actually exceed the speed of sound, producing negative lift, which killed fuel flow. Despite -11g, Dittmar managed to pull out and re-light the burner. His speed record, initially top secret, would stand almost six years. With a wingspan slightly less than the Me-109 (30.5 feet), the 163 had 18% more wing area; even unpowered, it boasted a glide angle of 1:20. (Modern hang gliders only achieve 1:15, though wide-winged sailplanes can do up to 1:60.) The 163’s aerodynamics were almost too good. At anything over 400kph airflow held the clamshell canopy shut, making bailouts problematic. Veteran Wasserkuppe pilot Lt. Rudolf “Pitz” Opitz, who had flown DFS-230 gliders in the invasion of Belgium and now backed Dittmar as second test pilot, remembered, “The canopy would float one inch over the frame. It wouldn't blow off....We took a broomstick along to try to push up the nose section of the canopy to get it out in the slipstream and make it break off.” In the spring of 1942 Eprobungskommando (Operational Trials Command) 16 was formed to train rocket-fighter pilots. Prewar gliding champion Captain Wolfgang Späte, now a top ace with Jagdgeschwader 54 on the Russian front with 80 victories and Oak Leaves to his Knight’s Cross, was given command. “Air defense of the homeland is going to be important,” General of Fighters Adolf Galland told him. “...I want to bring the Me-163 to combat-ready status as quickly as possible.” The unit set up shop at Peenemünde, the top-secret test site on Germany’s Baltic coast. As adjutant Späte brought in his best friend, blue-eyed Viennese Lt. Josef “Joschi” Pöhs, a 43-victory ace with JG54 but still on crutches after bailing out of an Me-109. “I was able to drag him out of his sickbed in a flash with only a few hints about testing a rocket fighter,” Späte recalled. “...He was sure he could move his feet around enough to move a rudder. He still couldn’t depress the brake pedals, but that wasn’t necessary. The Me-163 didn’t have any.” On May 11 Späte climbed into the same Me-163A that Dittmar had used for his speed record seven months earlier, but this time for a “sharp start,” a rocket-powered takeoff. “An Me-109 accelerated better under full power, but with a propeller, the acceleration decreased as the speed increased,” he remembered. “Here the acceleration was constant....When I pulled the handle and the wheels fell away, it felt like I had just dug in my spurs....Now all I had to do was follow Dittmar’s instructions and keep the airspeed at 400km/h. To do it, I had to continually pull back on the stick. My attitude kept increasing until I was climbing at 45 degrees. Even then, the airplane wanted to accelerate.” Its handling amazed him even more. “Despite its unique tailless planform, the Me 163 was stable in every axis. This meant that at high speeds you could effortlessly make any course correction, in any direction, something that is of major significance for a fighter plane and is quite often lacking in other faster airplanes.”

“I found this creation of Lippisch to be an aircraft with flight characteristics so beautifully balanced that I have seldom flown one like it, either before or after this flight,” Späte recalled. “...In reality, we have a flying tailless Interceptor, an aircraft capable of 1,000km/h, and one which will hopefully swing the tide of the air war in our favor.”

Late-model Scheuschlepper. Early models used inflatable air bags to lift the Komet But if the 163 was a sweetheart in the air, it was a devil everywhere else. As with his sailplanes, Lippisch believed wheels were only necessary on the ground. 163 pilots dropped their main gear soon after takeoff and landed on an extendable belly skid. The dolly, neither shock-absorbing nor steerable, required operations off wide grass fields, since without steering a concrete strip would only have been useful if the wind was blowing along it. A combination tow motor/forklift, the Scheuschlepper (Shy Tug), retrieved it from the field, at first lifting it on airbags inflated under the wings. If the rocket cut out at low altitude, pilots were warned not to try to bank or turn with a full fuel load, but to put down straight away. “If at all possible,” suggested one, “heading straight into the cemetery to save expenses.” Rudi Opitz tests the 163B with a helmet-mounted camera (Silent) With all that wing area the 163 tended to float on landing. High landing speeds (100mph in the Anton and 137mph in the “Berta” ) made overshoots common. On unprepared ground the belly skid often dug in like a plow; nor did it much soften a hard landing, as Dittmar learned when he stalled a Berta at 12 feet and slammed it down on concrete. Its skid collapsed. The shock went straight to his spine. With his fifth thoracic vertebra broken, Dittmar was grounded for two years. He was lucky. Me-163 pilots quickly became experts at dead-stick landings, or they died. Heini Dittmar and Hanna Reitsch with Me-163 (Silent) Despite the difficulties, or because of them, the challenge of rocket flight was undeniable. Famous aviatrix Hanna Reitsch, the German Amelia Earhart, used her friendship with Adolf Hitler to wrangle rocket flights in the Anton and glide flights in the Berta. On October 30, 1942, on her fifth flight in a Berta, its undercarriage dolly refused to separate. Reitsch missed the runway, came down across the grain of a fresh-plowed field and dug in, banging her face on her gunsight, breaking her cheeks, jaw and skull and almost tearing off her nose. Though she spent six months in the hospital, she still insisted on being the first to fly a sharp start in the B. Späte (who thought her a primadonna) forbade her to further risk herself. She never flew it again. By 1943 Peenemünde was the wunderwaffe capitol of the world. Along with the Me-163, radio-guided and wire-guided glide bombs and the V-1 cruise missile were being tested. Späte’s pilots watched the first test shots of the V-2 rocket, one of which heeled over on liftoff and came down on their field, blowing up a pair of five-engine twin-fuselage Heinkel He-111Z tow planes. “Our Me-163 was counted as one of the V-weapons,” Späte remembered. “...V-weapons! Those familiar with the programs knew with secret horror that, of all the new weapons, not one was ready for deployment with our combat forces.” With its low fuel capacity and relatively low-power motor, the 163A could only reach 16,000 feet, not enough to reach high-flying Allied bombers. Lippisch’s Me-163B, the “Berta,” was bigger, easier to produce, and could carry more fuel, not to mention wing guns. Whereas the 163A’s “cold” rocket burned at 800°, Walter was developing new “hot” motor, burning T-Stoff and C-Stoff (30% hydrazine hydrate solution in methanol) at 2,000°. It being absolutely critical that T-Stoff and C-Stoff never came together except in a combustion chamber, there were separate handling crews for each. T-Stoff, which corroded iron and steel, had to be kept in aluminum tanks, but C-Stoff ate through aluminum, and had to be kept in glass or enamel. All T-Stoff containers were white; all C-Stoff containers yellow. Fuel trucks, clearly marked T or C, were forbidden to come within 800 meters of each other. Pilots wore flight suits of synthetic fiber polyvinylchloride impervious to T-Stoff, at least until it leaked in through the seams.Shortages of C-Stoff and reliability problems—thrust cut-outs, explosive combustion-chamber failures—would delay deliveries of the “Hell Machine” by a year. The endless delays with the Walter motor put the rocket-fighter program on indefinite hold. “The Me-163,” Späte learned, “unfortunately doesn’t have the same priority as U-boats, tanks or AAA [anti-aircraft artillery]. And because of it, we continue to experience all these delays.” The RLM went so far as to ask BMW to come up with an alternative design burning nitric acid and methanol, which came to nothing. Meanwhile jet-engine technology had caught up and was moving literally full-speed ahead. Späte even test-flew a prototype Me-262. He found it neither as fast nor as maneuverable as his rocket fighter but, with its greater endurance, far more practical. “The Me-163 was a small, polished dagger,” he concluded. “The Me-262, on the other hand, was a large sharp sword....It was the means to swing the course of the war back to our side.” Disdaining the 163 with a “not invented here” attitude that eventually drove Lippisch from the company—or simply seeing the writing on the wall—Messerschmitt focused on their in-house Me-262 jet. Späte complained, “They believed the Me-163 would probably be the next project to ‘get the axe.’”

General of Fighter Pilots Adolf Galland (moustache) attends the preview of the Me-163A at Lechfeld, Bavaria. Heini Dittmar in white coveralls, Späte in profile to right, Opitz smiling at camera On Thursday, June 24, almost a year later than planned, and in front of Luftwaffe dignitaries including Galland and Field Marshal Erhard Milch, Luftwaffe Air Inspector General, Opitz made the first sharp start in a 163B with the new Walter rocket. Halfway down the runway, still well below takeoff speed, he hit a bump that lofted the 2-ton plane a dozen feet in the air. On coming back down it tore off its right wheel. With the left banging loose on the fuselage (and a fire truck already setting off after him), Opitz stomped full right rudder and rode the skid for 300 feet before he lifted off, dropped the remains of his undercarriage, and flew a perfect demonstration flight. When he touched down, eyes streaming with T-Stoff fumes leaked from a ruptured line, Milch awarded him 5,000 marks for dangerous duty. The Me-163B, now called the Komet, was ordered into production. A week later Lippisch left Messerschmitt. The Allies were becoming aware of German rocket research. On July 26 an RAF Mosquito snapped photos of parked, bat-winged aircraft which Allied analysts designated “Peenemünde 20.” Over the night of August 17/18 almost 600 RAF bombers pummeled the base: just a taste of the destruction to be wrought on German cities as the Allied bombing campaign intensified. EK 16 relocated to Bad Zwischenahn, near Bremen. Townspeople, to whom rocket fighters overhead became nothing unusual (they called the Me-163 the “Moth” ; pilots nicknamed it the “Thunderbird” or “Powered Egg”) asked, “When are you going to employ your force and sweep the skies clean again?” Me-163B testing (Silent) Eleven Me-163Bs were destroyed when the Messerschmitt plant was bombed. Production, farmed out to Klemm and Junkers, was hampered by lack of engines and components. There were critical shortages of C-Stoff, trucks to transport C-Stoff, and tanks to store C-Stoff. Joschi Pöhs resorted to mock-dogfighting student pilots in Fw-190s when they overflew the base. “He so adeptly and skillfully used the turning capability and airspeed of his small rocket bird, as well as the acceleration power of the engine,” approved Späte, “...the student pilots fled for home in their FW-190s.” “The men are dying to do something positive for our air defense,” Pöhs excused. “It’s an impossible situation for them to sit here week after week waiting, while bombers roar over and destroy our cities.” Meanwhile Späte devised operational plans for deploying Komets when they finally arrived. “We should systematically disperse squadron-sized units in a network of suitable airfields,” he recommended to Galland, “...between 60 to 150 miles apart from each other. They should be built in a chain which enemy aircraft will have to fly over.” The first 47 163B-0 models carried one 20mm cannon in each wing root. By 1944 this was already light armament, particularly against big, armored bombers. In the later 163B-1 models the Mk 151 was replaced with the 30mm Mk 108. Lt. Gustav Korff, a communications specialist from the Russian Front, signed on as the unit’s ground controller, pioneering new radar guidance equipment and techniques necessary to steer rocket pilots, within minutes, onto targets initially too high for them to see. Finally, late that year, Späte and Pöhs visited Augsberg to test-fly the first production Bertas. Späte suited up in a polyvinylchloride hood, coveralls and overshoes. “I felt like a mummy,” he recalled. “...But wearing the suit gave me the confidence that I had a certain amount of protection against that cursed T-Agent....The designers had installed fuel tanks (in the wrong place) to the left and right of the pilot’s seat. A simple sheet of pure aluminum separated my legs from two 60-liter tanks gurgling with T-Agent. A small accident on takeoff and you’re sitting in a flesh-dissolving solution....” However, he soon forgot any doubts he’d had about the rocket fighter. “Now I was about to find out what the Walter engine and my little Me-163 actually had in them. After the wheels dropped and the skid retracted, the aircraft really started to step out.” The Anton climbed 45° at 400km/h; the Berta, even steeper at 600km/h. In 3½ minutes it could reach 40,000 feet. “This was a special kind of airplane,” Späte knew, “...an extremely good feeling aircraft, an elegant, lightning fast, easily controllable dart....I had experienced something today that even the Me-163A didn’t have to offer. You really could intercept any other aircraft with this bird.” His only complaint was an excruciating need to fart: “I swore to myself that I would never again eat pea soup and heavy cornbread before a flight in a rocket fighter.”

Me-163 V8 CD+IM Späte and Pöhs returned to Peenemünde to await deliveries. On Dec. 30 Späte was doing paperwork in his office when he heard another training flight of FW-190s overhead, then the roar of a 163A taking off. “Pöhs presumably was going to take this opportunity to chase them away,” figured Späte, who remembered suddenly jumping out of his chair. “The sound of the engine had quit abruptly....The engine must have flamed out shortly after takeoff....Then an explosion shook the barracks walls and windows as though a bomb had gone off.” Späte jumped in a car and raced to the crash site, 1½ miles away on the far end of the field. It was Pöhs. “He had not tried to bail out as the airplane had never got high enough for him to use his parachute. He had succeeded in turning the aircraft back towards the base—among us pilots, that was known as the ‘death turn’ since so many have crashed attempting it. But, as he soared in over the landing area, he came face-to-face with a radio antenna. He didn’t have enough controllability left to avoid it. He clipped the tower with a wing tip and the aircraft did what we call a ‘pole vault,’ digging a wing tip in the ground and cartwheeling.”

Not the Pöhs crash (this is the Me-163B of Unteroffizier Manfred Eisenmann, Oct. 7, 1944), but similar in outcome. Eisenmann was killed. The Messerschmitt’s remains lay on its back. “I saw two legs protruding from the broken nose section. They belonged to my best friend! Mindlessly ignoring all regulations, I waded through the [extinguishant] slime and foam to the airplane and looked into the crushed cockpit area. I recognized that there was absolutely no chance of survival....‘I want everyone who is not directly connected with the recovery operation to leave the scene immediately,’ I ordered.” The accident report concluded that when Pöhs dropped his undercarriage, it had rebounded so hard and high that it stuck the aircraft’s belly, breaking a T-Stoff line and causing the rocket to automatically shut down. Worse was the post mortem report: while Pöhs was trapped in the cockpit, he had been inundated with T-Stoff. “Even though he was wearing a protective suit,” Späte was told, “his entire right arm had been dissolved by T-Agent. It simply wasn’t there. The other arm, as well as the head, was nothing more than a mass of soft jelly.” His friends could only hope Pöhs had been killed instantaneously or at least knocked unconscious in the crash. In January 1944, nearly two years after delivery of the first 163B, EK 16 finally received its first operational models, but “operational” did not mean gremlin-free. The unit spent weeks wringing them out to resolve engine flame-outs and other issues. In February, Späte suffered a ruptured fuel line on takeoff. With his cockpit filling with T-Stoff fumes, his overheat indicator lit up, and his fuel-dump valve lever inoperative, he had to put his flying bomb down on six inches of snow: “The bird started sliding on its steel skid like a skier coming down a well prepared slope.” Before it skidded off the airfield grounds into the trees, Späte popped his canopy and rolled off the wing, sustaining a concussion in the process. “It was unthinkable,” he wrote, “to consider sending a single airplane that had such an unreliable engine into combat, let alone deploying an entire squadron.”

Rocket Attack by Nicolas Trudgian Buy the print

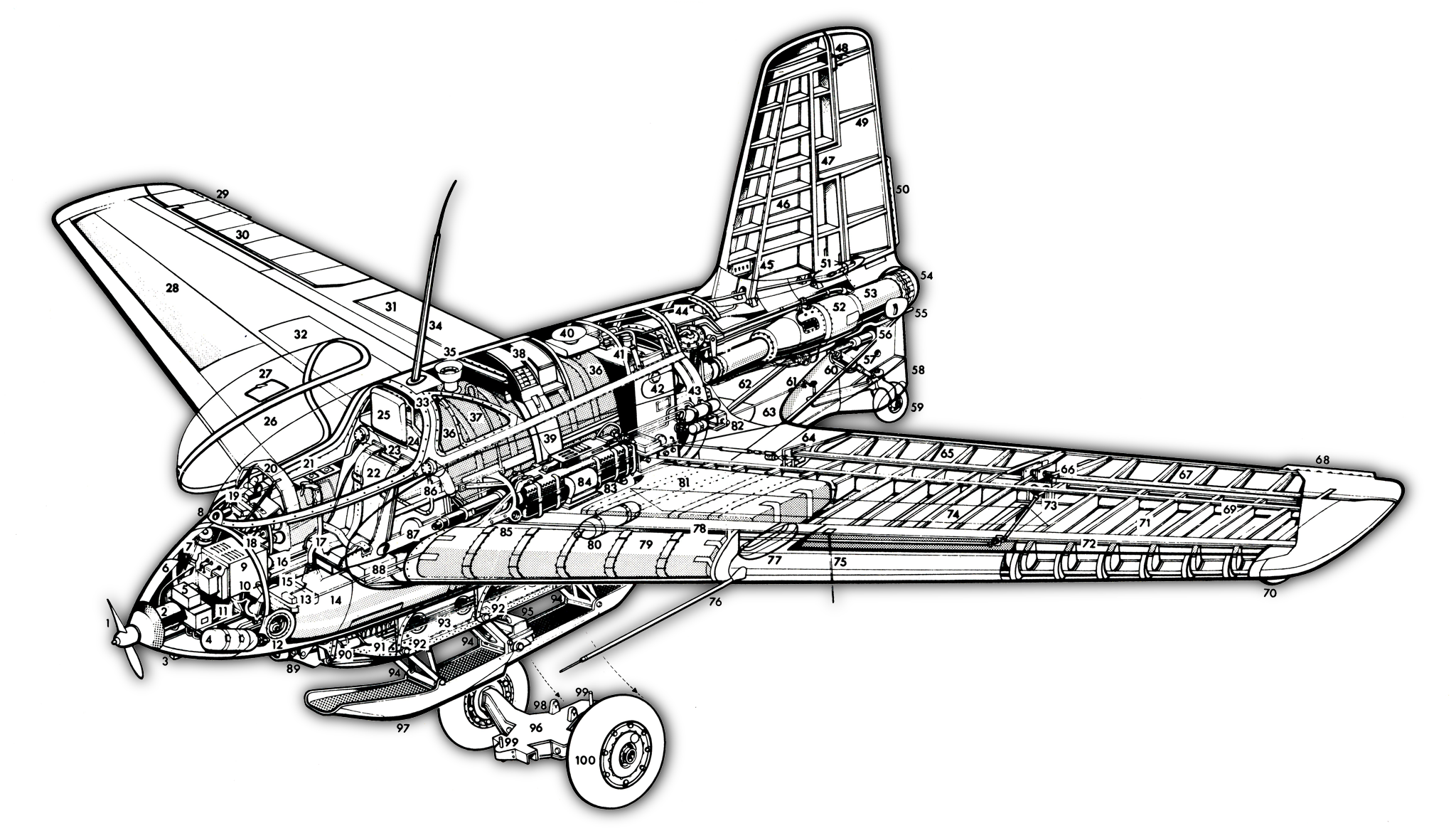

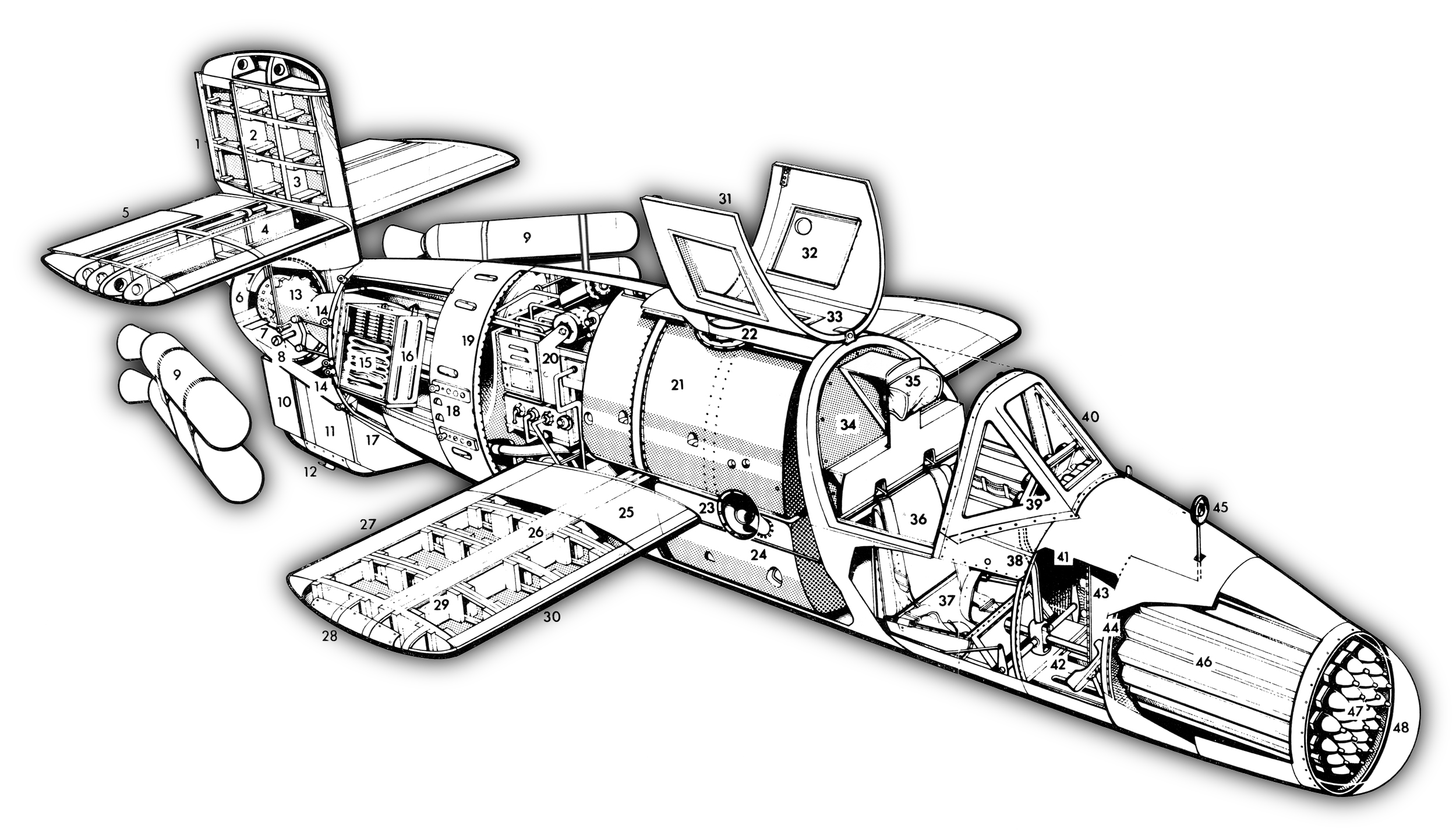

Messerschmitt Me-163B-1a

1 Generator drive propeller

34 FuG 16zy radio receiving aerial

69 Rear wing spar First kill of a rocket fighter?

Lightning Strikes a Komet, by Roy Grinnell The day after Tacon’s inconclusive tangle, Capt. Arthur J. Jeffrey, leading four P-38J Lightnings of the 479th Fighter Group, spotted a crippled B-17G, She Hasta, of the 100th BG: “We were on an escort mission for heavy bombers returning to England. As I looked out over the formation of aircraft below me, I saw a crippled B-17 that was terribly shot up—pathetic, really. It had only about two-and-a-half engines running, and half of its tail was gone. The aircraft was just shot all to hell. But the worst thing was that bomber was on a northwesterly course, which meant that it would miss the British Isles completely. “It was a grey day, and we were over Holland, which was blanketed by intermittent layers of cloud. The B-17 was steadily losing altitude. We’d found that when bomber navigators got separated from their lead navigators they had all sorts of trouble remaining on course. I called my second element leader to stay up and cover us while I went down with my wingman to give the B-17 a steer because it was so God-awfully lost. But I couldn’t raise the crew on the radio—I guess all their sets were shot out." Jeffrey moved in on damaged bomber to hand-signal its crew, but despite his P-38’s distinctive planform the bomber’s rookie gunners fired on him. “At least they were alert,” Jeffrey thought.

“‘Yellow Four’ provided top cover. The B-17 plodded along at 11,000 ft, dodging holes in the overcast to keep out of the flak, and at 1145 hrs I observed an Me 163 in attack position behind it. The Me 163 made a slight low-side ‘five o’clock’ pass at the B-17, followed through in a slight dive and then levelled off. At about this time the German must have seen me because he made another slight dive. He then started a very steep climb, weaving all the while, as though he were trying to see behind him. During this weaving I closed with him and opened fire, observing strikes on the Me 163. “At 15,000 ft it levelled off and started to circle to the left, as though positioning himself to attack me. I could turn tighter than he could, and I got in a good deflection shot, with the closest range estimated to be 200 to 300 yards. I thought I was getting hits but my shots seemed roo far away for effect when puffs of smoke started to emanate from the tail of the jet. “The pilot didn’t seem to know what to do in a fight—he didn’t act like he had been in combat before—and at about 15,000 ft he turned and attacked, with me looking right down his throat. He was pretty green. We got into a tight circle and I saw some good deflection shots hitting him. Then he rolled over and went straight down, with me fire-walled behind him. For the first time in my life I found out how—at over 500 mph—your props can act as brakes. I was shooting at him as I was going straight down, and my tracer path was walking forward of the ‘bat’. Then I got into an arc of an outside loop, and when I finally pulled out a few hundred feet above the ground, I blacked out.” Jeffrey’s wingman, Lt Richard G Simpson, reported, “After about 4000 ft of climbing the Me 163 turned to the left and Capt Jeffrey attacked again. I had one bad engine and couldn't climb as fast, so I couldn’t see if he was getting strikes or not. Then the Me 163 split-essed and went down into a very steep, almost vertical, dive. Capt Jeffrey and I followed, but I couldn't keep up with them. I started to pull out at between 3,500-4,000 ft, indicating a little over 400 mph. The Me 163 went into the clouds, which were at around 3000 ft, still in a dive of 80 degrees or better. He must have been indicating 550-600 mph, and showed no signs of pulling out. I don't see how the German could have gotten out of that dive.” Jeffrey claimed a probable, and was famously awarded the first rocket-fighter kill of the war, but the Germans actually recorded no Komets lost or even damaged that day. The 163 was so slippery that, even with its engine off and tanks empty, it could out-plummet Allied fighters diving on full power, and with those big bat wings, pull out later too. (Lightning pilots were actually forbidden to power-dive because compressibility might tear the tail off their airplane.) As Lieutenant Hartmut Ryll put it, “Our bird hangs in there, steady as a rock. The Americans break off their attack relatively early. And by the time the airspeed dissipates back out of the 900km/h area, you're already back in the local area and under the protection of our own flak.”

Playing the Last Ace, by by Heinz Krebs Me-163 Komet fighters climb vertically through an 8th Air Force bomber formation and its top fighter cover before swooping down to attack the “heavies.”

Me-163S Several 163B models had their rockets and fuel tanks deleted to make two-seat trainers, with the instructor in the rear seat and water in the fuel tanks to simulate changing fuel load. The Russians took at least one of these back to the USSR after the war.

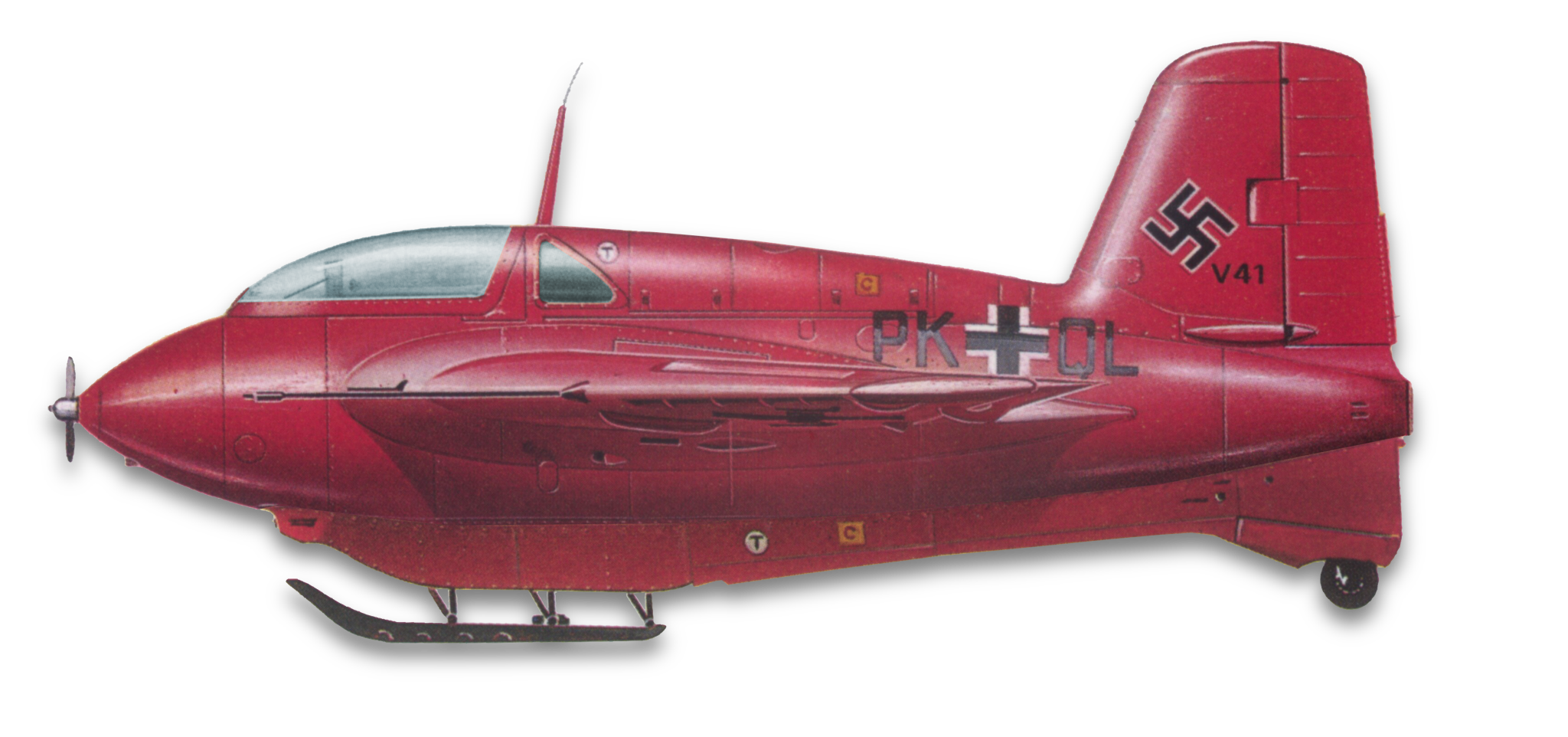

Me-163B-0 V41. On Saturday, May 13, 1944, Major Wolfgang Späte flew this fighter, in this paint scheme, on the world’s first rocket-fighter sortie. It was unsuccessful.

Baptism of Fire, by Marii Chernev Brandis, August 1944: As Unteroffizier Kurt Schiebeler flees for home in Messerschmitt Me-163B V53, W.Nr. 16310062 “White 9,” P-51 Mustangs of the 353th Fighter Group brave German flak to give chase. Once on approach, a rocket pilot was powerless to evade. “White 9” survived the war, only to be was blown up by the Germans at Brandis in a futile attempt to keep rocket technology out of Allied hands. Top-scoring rocket-fighter pilot of all time Sgt. Siegfried Schubert (Silent)

Lt. Charles Laverdiere’s B-17 XK-B of the 305th Bomb Group after its return to Chesterton, UK, 8-24-44. Damage often attributed to Ryll, but consistent with Schubert’s gun-camera film. Me-163 gun camera film, 8-24-44

On August 24, 1944, Sgt. Siegfried Schubert claimed one B-17 of the 92nd Bomb Group (Lt. Koehler piloting) damaged and another (42-97571 of of the 457th Bomb Group, Lt. Winifred Pugh piloting) destroyed. Unknown to Schubert, Koehler’s aircraft never reached England. On Sept. 8th Schubert’s gun-camera film was exhibited to Oberkommando der Luftwaffe (Air Force High Command), upon which General of Fighters Adolf Galland declared the Me-163 fully operational. On October 7th, Schubert shot down two more B-17s to bring his total to three. That same day he was killed when his Komet exploded on takeoff.

Efforts were ongoing to solve the rocket fighter’s lack of endurance and firepower. A spare 163A received under-wing racks with two-dozen unguided R4M rockets—a rocket-firing rocket—but they offered no improvement in range, trajectory or explosive power over 30mm cannon. More promising was the Jägerfaust, the “fighter fist,” ten recoilless 50mm wing guns automatically firing upward when the Komet passed under a bomber. Simultaneous firing initially blew off the 163B’s canopy. A sequential delay was built into the trigger system. Meanwhile Walter was working on a new rocket with (comparatively) long-range cruise capability. It was to be fitted into the stretched-fuselage Me-163C, but that was passed over in favor of the even more advanced Me-163D with retractable wheels, and finally the Me-263 with cruise rocket, landing gear, and pressurized cockpit. Only three prototypes, however, were complete by war’s end.

Me-163A with 24 R4M rockets The R4M was developed to offset the increasing weight of German aircraft guns capable of downing Allied bombers, specifically the 30 mm MK 108 cannon. Although each rocket was heavier than a 30mm shell, 24 rockets weighed less than the gun plus its usual 65 rounds. The R4M had a similar trajectory to the 30 mm rounds, requiring no change to the standard Revi 16B gunsight.

Me-163B-0 V45 Used for trials of the wing-installed, upward-firing, recoilless 50mm Jägerfaust mortar. Aircraft was badly damaged when simultaneous firing of all 10 projectiles blew off the canopy.

Me-163C To accomodate the new twin-chamber Walter rocket with cruise capability, Messerschmitt extended the 163B fuselage, added extra tank capacity and a new pressurized cockpit topped with a bubble canopy.

Me-163C Shown with B-type canopy. Maximum altitude increased to 52,000 ft, powered flight time to about 12 minutes, and combat time from about five minutes to nine. Three prototypes were planned, but only one was flown, and without its cruise rocket.

Me-263 (Ju 248) Fitted with tricycle gear and twin-chamber Walter cruise rocket (though the gear was probably not retractable in testing), the Junkers Ju 248 used a three-section fuselage to ease construction. The prototype was completed in August 1944 and glider-tested behind a Junkers Ju 188 but probably never tested under power.

Me-263 (Ju 248) Though designated Messerschmitt Me 263, Junkers continued development of three prototypes before the plant was overrun by the Russians. The Soviets briefly developed the design as the Mikoyan-Gurevich I-270, which was discontinued after two prototypes crashed. Note three-blade generator prop.

Mitsubishi J8M1 Shusui Rocket fighters also appealed to Germany's B-29-beset allies, the Japanese. Though various plans and components were lost in transit aboard sunken U-boats, they developed their own license-built Komet, the Shusui (“Powerful Sword”). On its first powered test on July 7, 1945, however, the prototype's engine cut out. It crashed. Pilot Toyohiko Inuzuka was killed.

Bereznyak-Isayev BI The Soviet BI was of more conventional layout than the Komet, but its rocket, burning kerosene and red fuming nitric acid, was no more reliable and contributed to airframe corrosion. One pilot was slightly wounded in a motor explosion and another killed in a crash when he lost control near the sound barrier. The BI never saw combat. Like the Germans, the Russians became more enamored of jets.

Captured Bachem Natters undergoing inspection by US troops. St. Leonhard im Pitztal, Tyrol, Austria, May 1945 With the Komet in perpetual development, in July 1944 the Luftwaffe established a Jägernotprogramm, Fighter Emergency Program: a quick and dirty solution to the Allied bombers pummeling Germany. Engineer Erich Bachem’s Ba 349 Natter (“Snake”) would operate more like a guided missile: a vertical-takeoff, semi-disposable manned rocket. The Luftwaffe rejected the concept, so Bachem put it in front of Heinrich Himmler. The Reichsführer-SS, desiring to give his personal army some air power, approved the idea.

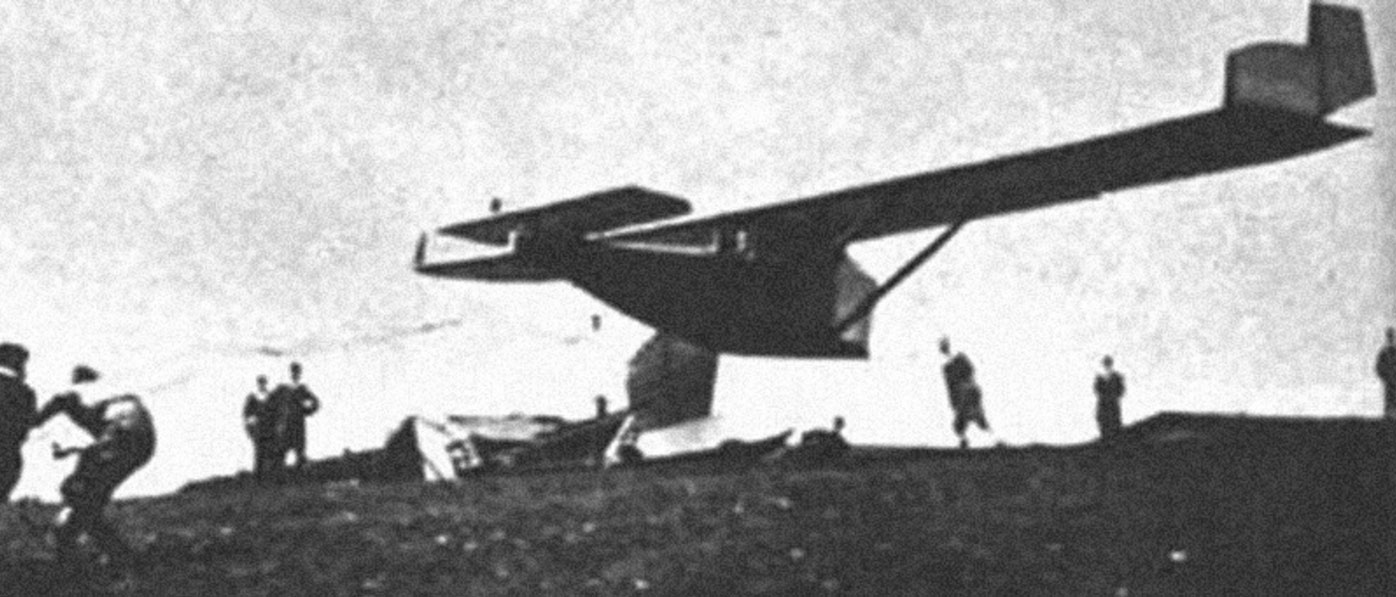

Bachem BA-349 Natter

1 Rudder

17 Parachute exit hatch

33 Roof glazing

Bachem BA-349 Natter

Bachem BA-349 Natter by Vincenzo Auletta Given more development time, the Natter might have presented Allied bombers with a second rocket threat

Seven GMC 2½-ton 6x6 Jimmy trucks with Me-163B Komets bound for the US. Possibly Merseburg, Germany.

Captured Me-163 gets a tow from a B-29 Superfortress. To this day the Me-163 Komet remains the only rocket-powered combat aircraft. Its pilots—those who survived—had the satisfaction of knowing they flew the hottest bird in the sky. In the final weeks of the war B-17 pilot Edward F. Reibold was startled to find a rocket fighter flying his wing, just out of machinegun range. “Without changing direction, he slid into within a few feet of our left wing tip,” the bomber pilot remembered. “We were, at the time, traveling at an airspeed of approximately 285mph. The pilot of the German plane hesitated off our wing, nodded, threw us a ‘Highball’, pushed his throttle forward and accelerated forward in flight leaving us ‘standing’ in mid air.” “They were all filled with an intractable urge to serve their Fatherland in a special way,” remembered Späte of his pilots. “...They were ready to give their lives in order to fulfill their dream of flying in a rocket.” Get the rest of the story in the November 2017 issue of AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Comments loading....

|