by Don Hollway

As appeared in the December / January 2016 issue of

History Magazine

Scotland Yard, headquarters of the Metropolitan Police

Excerpts from Mata Hari’s M.I.6 file, and her French passport. Click to enlarge.

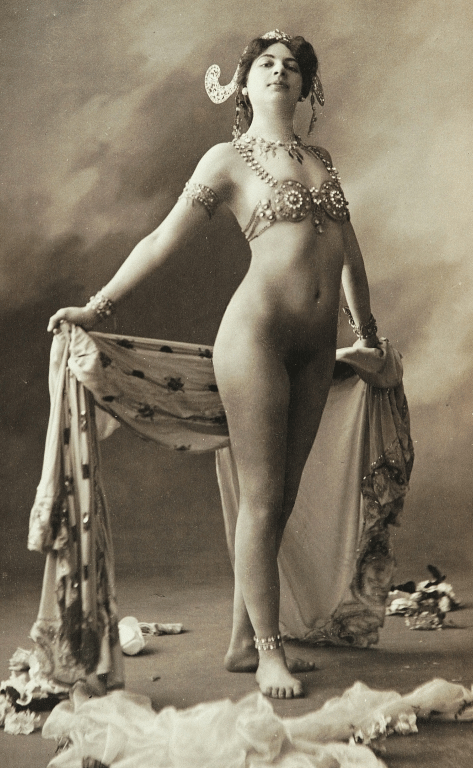

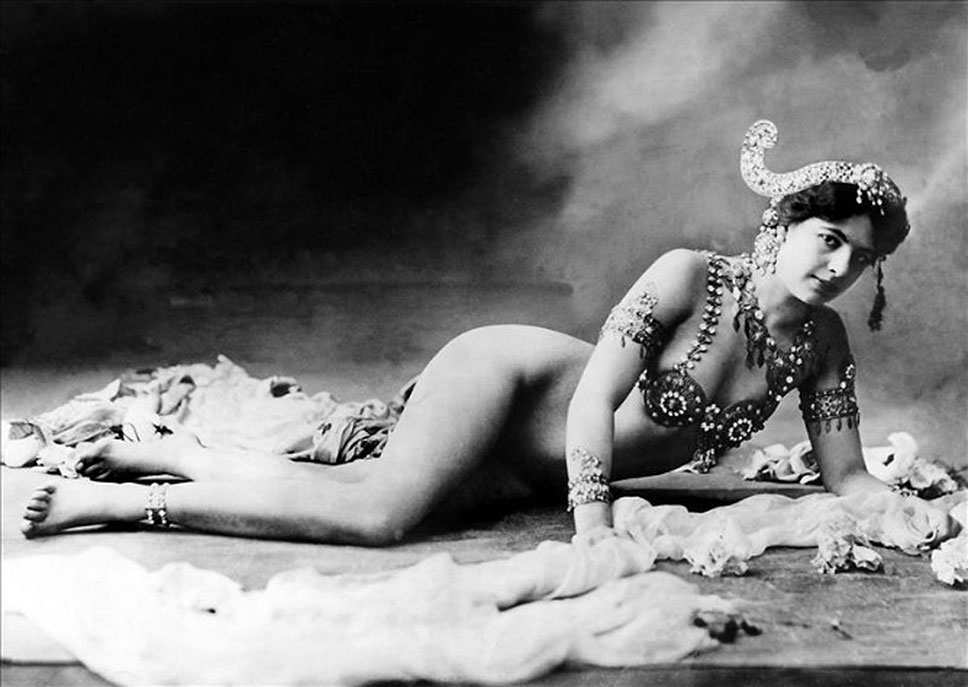

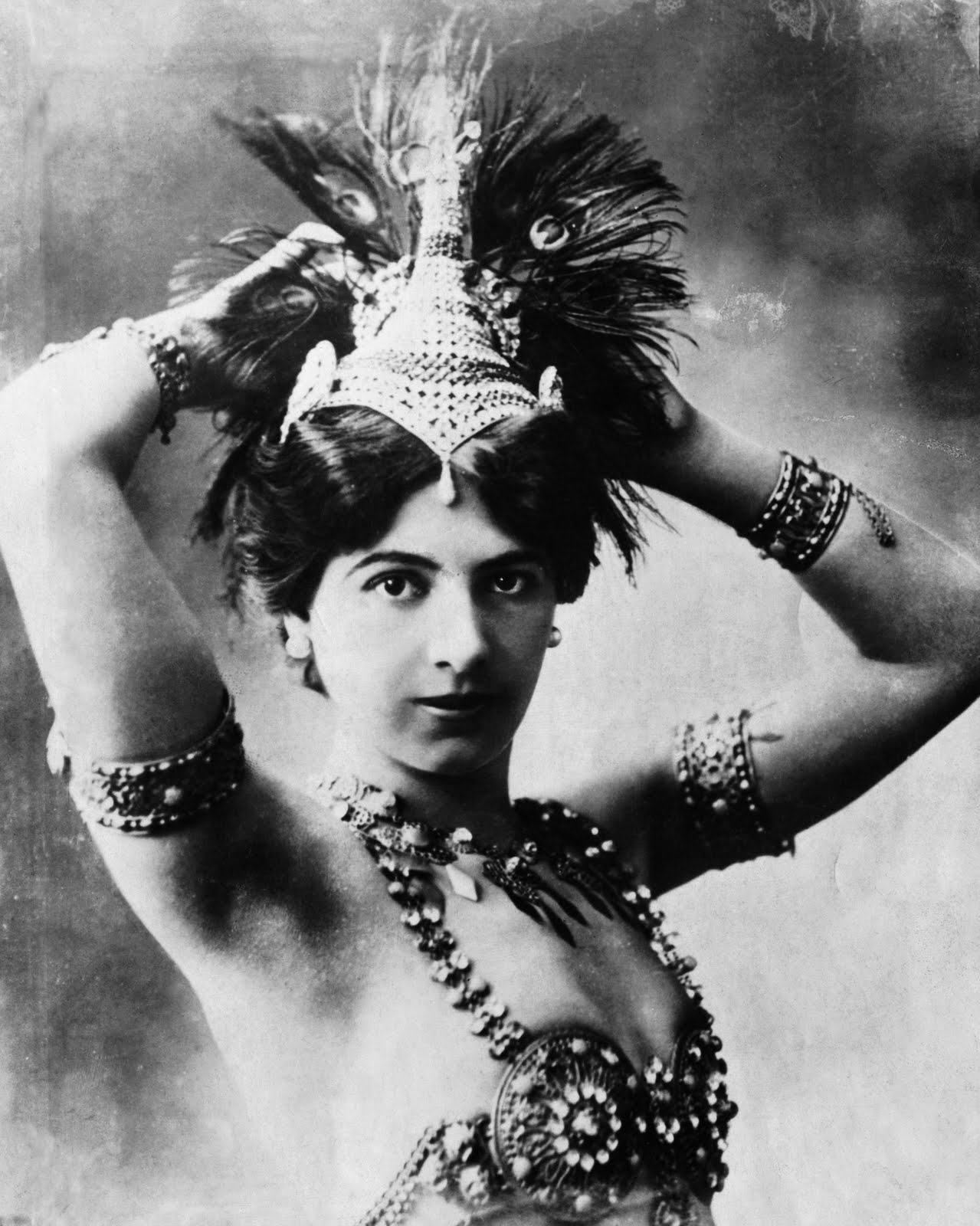

Margaretha MacLeod as Mata Hari, in 1905, the year she took Paris by storm. Colorization by klimbims

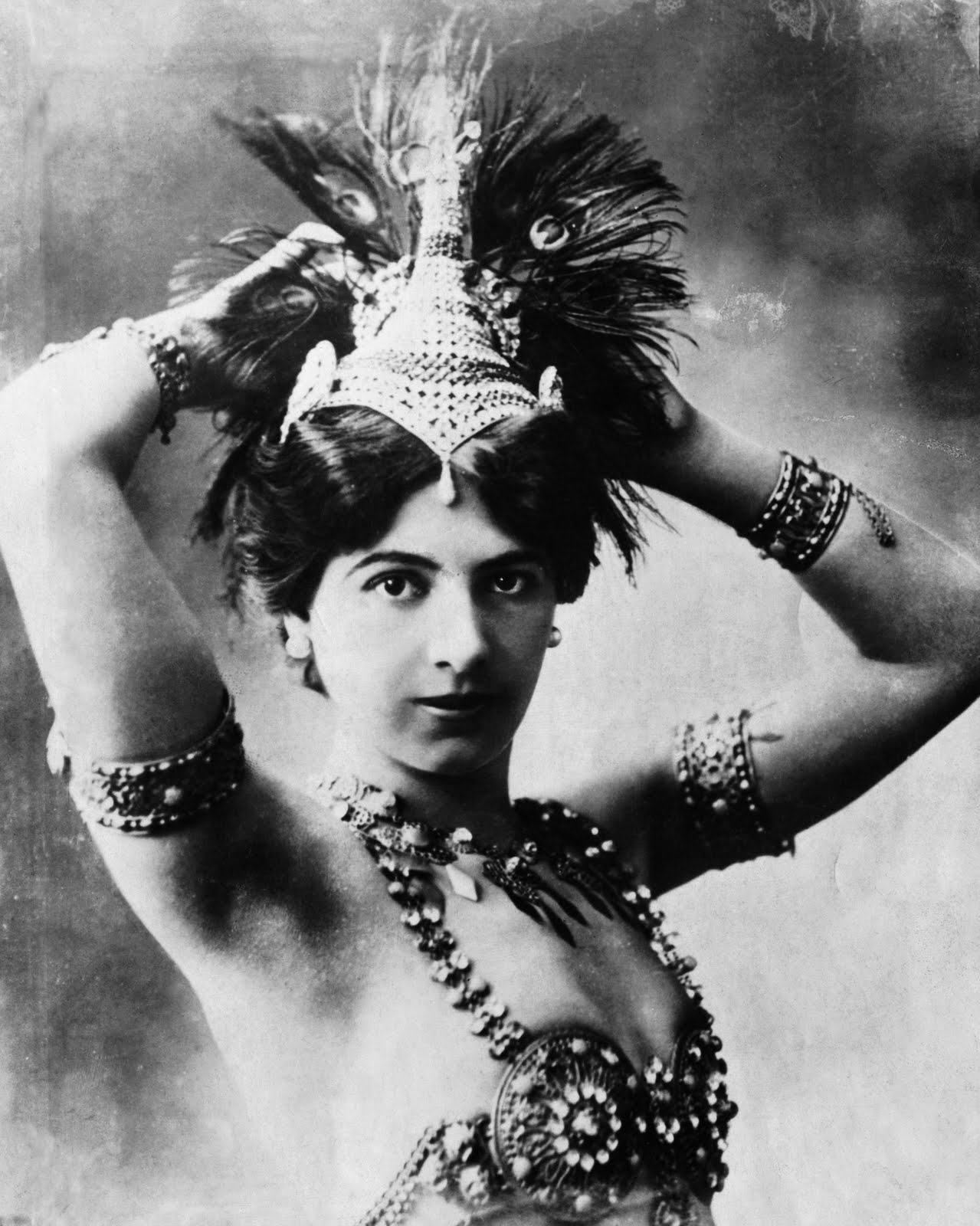

Four days of interrogation at Scotland Yard is usually enough to crack the toughest suspect. Yet Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner of Police and head of Special Branch, never quite answered the question that has intrigued historians for a century. His lovely, well-mannered Dutch prisoner, one Margaretha MacLeod née Zelle, was either an enemy spy, or simply the most famed exotic dancer and courtesan of la Belle Époque: Mata Hari.

“Three men in uniform interrogated me…in Dutch through a Belgian,” she remembered; the interpreter “had the audacity to say to the three men that I had a German accent.”

It was the Western Front of the First World War: Britain, France and Belgium against Germany. “We have information that Mata Hari received 15,000 francs from the German embassy,” Sir Basil told her. “We shall keep you in custody on suspicion of espionage and on the charge of having a forged passport.”

Her real crime, however, was being a woman of loose morals. Mata Hari freely admitted to a long list of lovers, from Paris to Berlin. Not even the British were immune. Her arresting officer said, “She was one of the most charming specimens of female humanity I had ever set eyes on,” and Sir Basil himself would remember her as “tall and sinuous, with glowing black eyes and a dusky complexion, vivacious in manner, intelligent and quick in repartee.”

Her allure was no surprise. Mata Hari had been charming, and manipulating, the men around her since she was a little girl.

The house where Margaretha was born in Leeuwarden burned in 2013 and was rebuilt, but not to the original design.

As a young girl Margaretha’s father, Adam Zelle, spoiled her with expensive gifts, like this goat-drawn cart

His fondness for ostentatious display and social grasping led him to risky speculation which bankrupted the family, broke up the marriage and forced Margaretha from her home.

Schoolgirl Margaretha, rear row far right

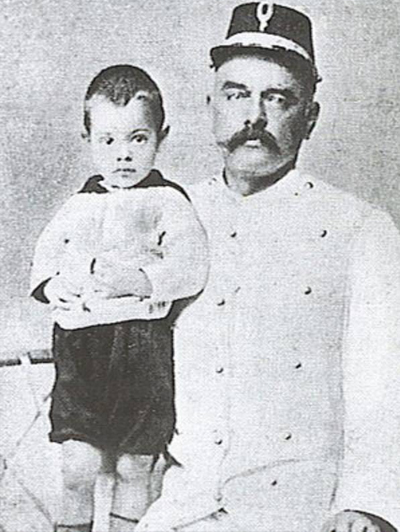

The eldest of four children and only daughter of a Dutch haberdasher and speculator who spoiled her as “an orchid among buttercups” but bankrupted the family, Margaretha grew up with relatives. When at 16 she was discovered in a compromising position with her 51-year-old school principal, blame did not fall where it would today. With few prospects, she eventually answered an ad by Capt. Rudolf MacLeod, a veteran of the Dutch East Indies wars more than twice her age, home on leave and seeking “a girl of pleasant character—object matrimony.”

As a young girl Margaretha was sent to live with relatives. At 16 her school principal tried to take advantage of her. Scandal ensued.

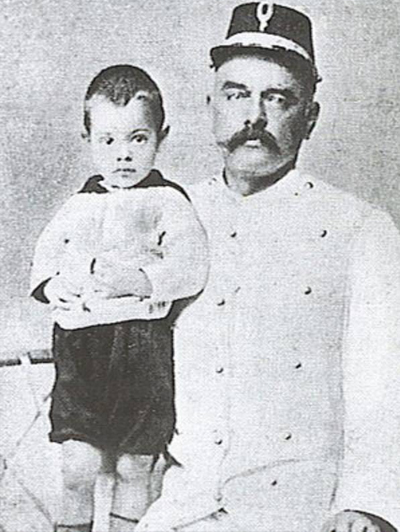

Margaretha was not quite 19 when she fell for Rudolf Zelle, a syphilitic drunk and gambler twice her age. She would always have a weakness for uniforms.

As the wife of an officer, Margaretha hoped to reattain the standard of living she had enjoyed as a girl.

“He could almost have been my father. Seeing a handsome young man made my heart start to beat faster.... I was very temperamental. I had also artistic aspirations.... I wanted to live like a butterfly in the sun.”

—Margaretha MacLeod

In 1897 Margaretha (front row, left) followed her husband (back row, second from left) by boat to his posting in the Dutch East Indies. Notably, she wears the same dress as in the photo above.

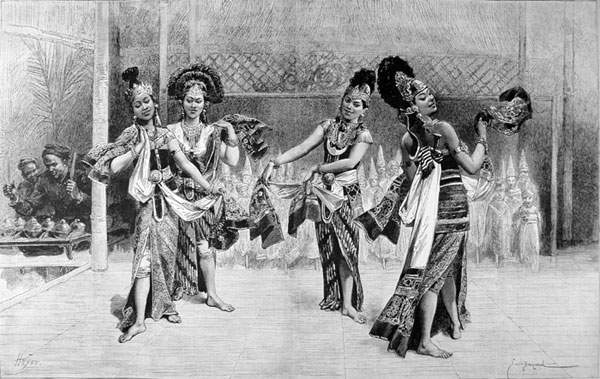

In the Indies Margaretha became familiar with Gandrung, a traditional dance of Indonesia. Four such Javanese dancers had appeared at the Paris World’s Fair in 1889. Originally a demonstration of love and dedication to Dewi Sri, the goddess of rice and fertility, by the MacLeod’s day the dance had become a simple courtship rite. Hip-thrusting female dancers, dressed in traditional costume including ornamental headgear, picked partners from the audience, who (importantly to Margaretha’s later act) donated money in appreciation. Gandrung was usually performed all night. Such erotically charged events would likely have had a strong effect on a young European girl. Young Margaretha, only just overcoming her Victorian morality, became a student of what must have been for her a semi-erotic art.

Margaretha’s stage debut in 1898 in a low-cut purple velvet gown drew officers’ eyes and drove Rudolf into a jealous rage.

When their son Norman John died under suspicious circumstances, the MacLeods’ marriage began to fail.

Their daughter Jeanne Louise (“Non.” ) survived the “poisoning.” but died in 1919 at age 21 without ever really knowing her mother.

As a young coquette on a military post in the sultry Indies, Margaretha was no better marriage material than MacLeod. “The young lieutenants pursue me and are in love with me,” she wrote. “It's difficult for me to behave in a way which will give my husband no cause for reproaches.” Rudolf had his own issues: gambling, drinking, womanizing, jealousy and spousal abuse, not to mention venereal disease. When their young son died, supposedly poisoned by a vengeful servant but more likely due to congenital syphilis, or its toxic mercury “cure,” the MacLeods returned to Holland and separated. He kept custody of their daughter. Margaretha started life over. Years later she told an interviewer, “I thought all women who ran away from their husbands went to Paris.”

City of Light

Paris during La Belle Epoque

“I took the train to Paris without money and without clothes. There, as a last resort and thanks to my female charms, I was able to survive.”

—Marguérite, Lady MacLeod

Paris was then at its fin de siècle artistic and cultural peak. Louise Weber, Jane Avril and Liane de Pougy had made it famous, and become famed, for the high-kicking, knicker-flashing can-can at the Moulin Rouge and Folies Bergère. In those high times a scandalous lifestyle was not to be hidden but shown off, a cause celébrè. The glittering façade, however, overlaid grinding poverty, barely repressed debauchery and a level of inequality perhaps unmatched until today, a century later. While powerful men in waistcoats and top hats openly flaunted their mistresses on the Champs Elysées and along the Seine, for an unemployed single woman the choices were few and mostly involved servitude: domestic, or sexual, as a grande horizontale. A prostitute.

Margaretha—now Marguérite—sought work as an artists’ model, but her figure was judged not up to the job. A skilled horsewoman, she applied for work as a riding instructor and then, growing more desperate and reportedly flirting with whoring, as trick rider with the Circus Molier, whose owner instead introduced her as a dancer to the salons of one of Paris’ upper-class doyennes. In those days of no radio, no television, no cinema, these high-society salonnières allowed the rich and powerful to enjoy themselves in intimate surroundings without rubbing elbows with the masses.

Lady MacLeod in the headdress she wore for her earliest appearances. In those days even a glimpse of underarm bordered on the erotic.

With no classical dance training, too tall to pass as a ballerina, Marguérite knew she needed an angle to set herself apart as more than a common dance-hall girl. In Europe all things Oriental were then the rage, as was a new naturalism in dance. American Isadora Duncan had become famous for going so far as to appear barefoot in a leg-baring toga. Marguérite went a step further. Knowing her skill was not in her movement, but in her sex appeal, she used one to cover up the other. She harkened back to her days in the Indies, taking a stage name from the Malay mata, eye, and hari, day—“Eye of the Day,” meaning the sun. Capitalizing on her status as the wife of an officer, but billing herself as his widow, she gained entry into the circles of the upper class, to which she would otherwise have been barred.

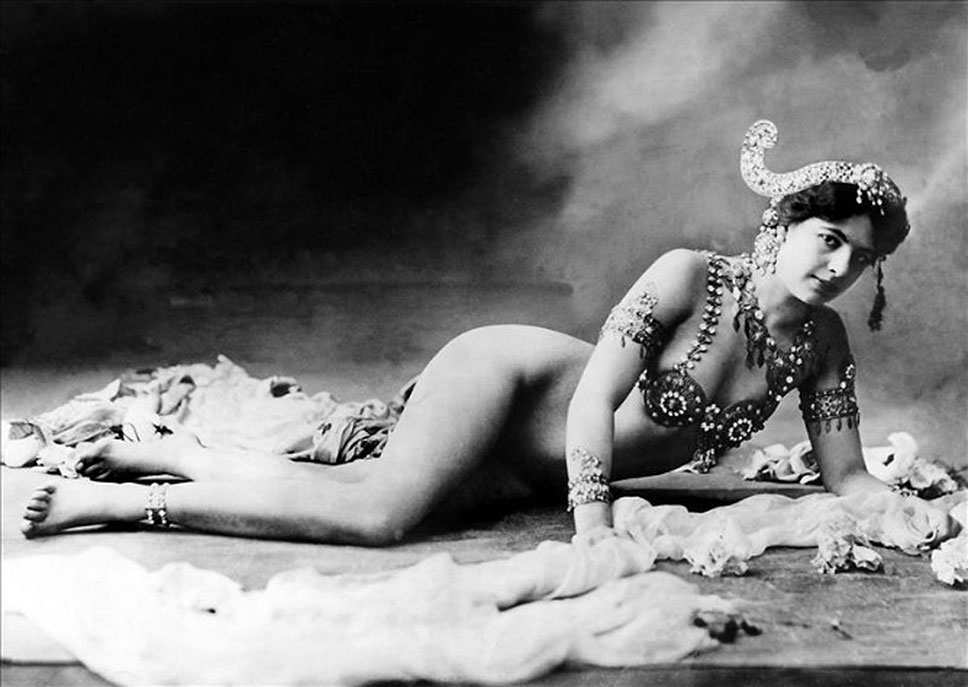

In February 1905 she made her first exclusive appearance in a Paris salon. Her strategy was simple; her routine, billed as a sacred invocation to Siva, Hindu god of destruction, combined raw eroticism with a veneer of religiosity. She appeared in a costume of her own design—diaphanous veils and metallic brassière, a cache-siens adorned with fake jewels—and, before an idol of the god, took it off piece by piece, working herself up to a fever pitch, at the climactic moment prostrating herself all but naked at his feet.

That the act was entirely made up of whole cloth went completely unnoticed by these enthusiasts of cultural authenticity. When a respected reviewer wrote breathlessly in a society magazine, “Lady MacLeod is Venus,” her career was made.

Musée Guimet, 13 March 1905

In these publicity stills of her first public appearance Mata Hari wears a fleshtone body suit for the camera (no navel), which she famously did not wear in her actual appearance. Her audience numbered in the hundreds, including high-ranking men of state. Click photos to enlarge.

“In my dancing one forgets the woman in me, so that when I offer everything and finally myself to the god—which is symbolized by the loosening of my loincloth, the last piece of clothing I have on—and stand there, albeit for only a second entirely naked, I have never yet evoked any feeling but the interest in the mood that is expressed by my dancing.”

By the next morning the Paris papers were all agog over the new star in the firmament. The Gallic called her performance “far from the entrechats of our classic dancers.” The Press said she “dances with her muscles, with her entire body, thus surpassing ordinary methods.” Parisian Life described her act more succinctly: “She wears the costume of the bayadère, as much simplified as possible, and toward the end she simplifies it even a little more.”

In 1905 the fabulous Mata Hari was the sensation of Paris. Her backstory changed every time she told it, variously as the daughter of a Hindu priest with a white woman or Scottish lord’s indiscretion with a Malay temptress who died in childbirth, leaving her to be raised as a temple dancer and bring the secrets of the mysterious Orient to the salons of upper-class Europe.

Mata Hari had made the leap from erotic dancer to artiste. She acquired the management services of Gabriel Astruc, famed for bringing the Ballets Russes de Monte Carlo to France. He booked her into Paris’s top music hall, the Olympia, for 10,000 gold francs.

“I never could dance well. People came to see me because I was the first who dared to show myself naked to the public.”

Colorization by klimbims

Her husband sued for divorce, using her seminude photos as evidence of bad character. Her father, who had sent her away as girl when his own finances failed, cashed in on her fame by approving a tell-all book. Ten years later her pain still came out in her interrogation transcript: “...My father married this woman. I always sent my father money.... Two writers went to my father, and asked if he would give his name, and she wrote the book, and my father gave my photographs. I have been very unhappy through this horrible book. She wrote this book, and my father gave the name, and one day 60,000 books went [out].... All Paris thinking I was twenty-eight years, and this said I was seventy-six or something like that.... All the people bought it. It was the great unhappiness of my life.”

Sigmund Freud was only just then establishing his theory of the libido, but today it seems plain that Margaretha sought father figures in an effort to recapture her childhood, as the object of an older, powerful man’s affection, and she had learned the hard way that sex was her lure.

“With every veil I threw off, my success rose. Pretending to consider my dances very artistic and full of character, thus praising my art, they came to see nudity, and that is still the case.”

The Toast of Europe

Mata Hari, 1906

As an artiste Mata Hari had gained entry into the salons of the wealthy and powerful; as a demimondaine she found her way to their beds. “From the moment that I introduced my Javanese dances, my fate was quickly decided,” she remembered. “...I received the protection of the richest strangers and I did not fail to profit from that.” The roll call of her paramours reads like a turn-of-the-century who’s-who: composers Jules Massenet and Giacomo Puccini; financier Baron Henri de Rothschild; chocolatier Gaston du Menier; the French ambassadors to Japan, the Netherlands and United States; the French minister of war. Banker Félix Xavier Rousseau put her up in a country château near Tours and a suburban Paris mansion, with fine furniture and racehorses, her own coach and a full staff, driving himself to financial ruin.

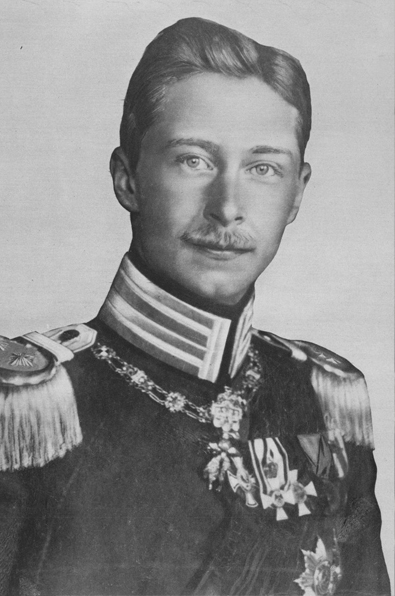

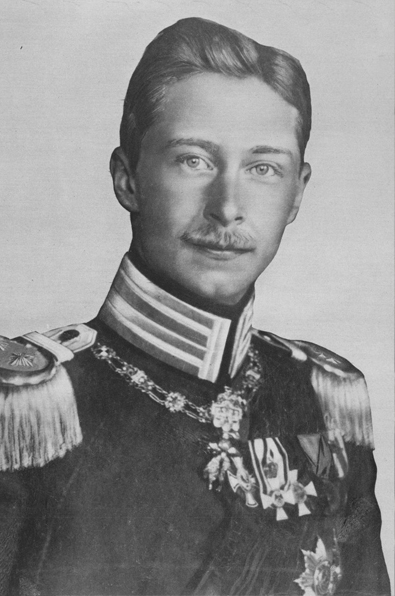

Having exhausted France, Mata Hari took her act to Spain, Italy, Russia, Austria and Germany. In Berlin her conquests included wealthy officer Alfred Kiepert, who gave her a parting gift of 300,000 gold marks (over $4.47 million today); the Duke of Cumberland, a cousin of English King George V who had sided with Germany and married his son to the Kaiser’s daughter; and even Crown Prince Wilhelm. A French interviewer wrote of her, “She has become Berlinoise and speaks German with an accent that is as un-Oriental as possible.”

Lover of Men

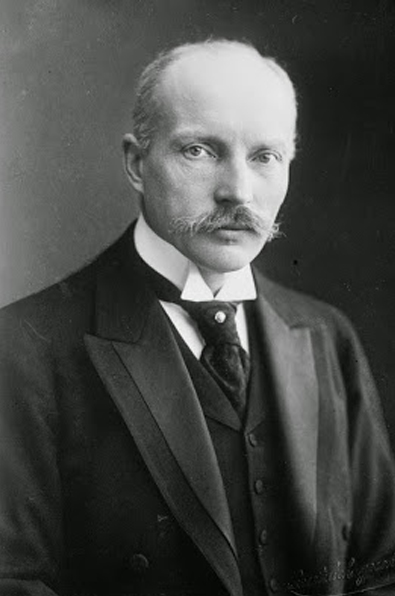

Jules Cambon, French ambassador to the United States, Spain, and Germany. During WWI he was head of the political section of the French foreign ministry.

General Adolphe-Pierre Messimy, French minister of war. He was blamed for the failed French Plan XVII and forced to resign on 26 August 1914.

German Army Capt. Alfred Kiepert took Mata Hari to observe German Army maneuvers. When his Hungarian wife, Martha, forced him to quit the affair, he gave Mata Hari a parting gift of 300,000 gold marks.

Crown Prince Wilhelm of Germany. Of him Mata Hari boasted, “I have already been [his mistress] and can do with him what I will.”

Lover of Fashion

At Longchamps during the Prix d’Automne,

4 October 1908

Berlin, 1907

At the Odéon, Paris, 1910

Ermine coat with fox mantles

At the Folies Bèrgere, 1913

1913

In her garden of her mansion at Neuilly-sur-Seine, as above

Berlin, 1906. Ermine goes with everything.

Monte Carlo, 1911

1913? Same dress as above and below.

In early 1914 Mata Hari landed a six-month engagement with the Metropol in Berlin, starting that September, for 48,000 marks (about $700,000 today). Requiring no nudity, it would have been her artistic nadir. That July, however, Austria invaded Serbia.

The Great War

German infantry, Second Battle of Ypres, 21 April – 25 May 1915. Note spike-topped Pickelhauben helmets, phased out in 1916.

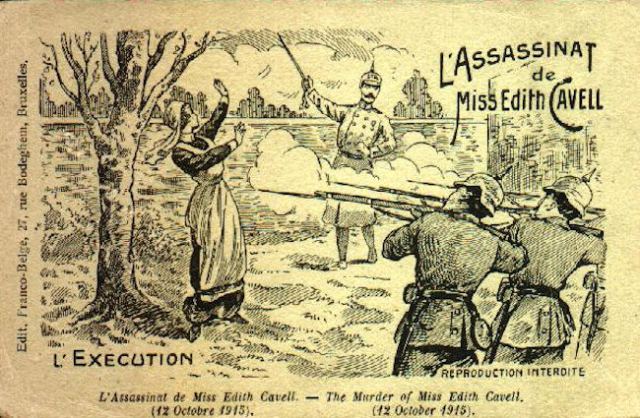

From its very inception with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife Sophie, the violence of World War I was not limited to men. The Germans in occupied Belgium imprisoned British nurse Edith Cavell for treason, after she helped wounded British and French soldiers and Belgian and French civilians of military age to reach neutral Holland. She was tried in military court, condemned, and shot on 12 October 1915. In death she became a more potent weapon for the Allies than she ever was in life, a propaganda tool that encouraged more men to enlist than she aided to escape. German Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs, Dr. Alfred Zimmermann, said, “It is undoubtedly a terrible thing that the woman has been executed; but consider what would happen to a State, particularly in war, if it left crimes aimed at the safety of its armies to go unpunished because committed by women.” The lesson would not be lost on the French.

The Germans seized Mata Hari’s furs, jewelry and luggage for being a Parisienne, or perhaps just as an unsubtle recruitment technique. Karl Kroemer, German consul to Amsterdam, offered her 20,000 francs for pillow talk with French officers. More, if it proved of value. “Then,” he told her, “you can have all you want.”

Mata Hari never turned down money from a man. In recompense for her lost belongings, she took the cash. “My 20,000 francs in my pocket, I bowed Kroemer out the door.”

British agents in Holland got wind of the deal and alerted the French: “She is regarded by Police and Military to be not above suspicion, and her subsequent movements should be watched.”

After her last performance as a dancer in the Netherlands,

March 1915

In Amsterdam in 1915, around the time she was first asked by the Germans to spy on the French

Evicted from Germany, Mata Hari is known to have spent the first year or so of the war in neutral Holland, in a home furnished to her by her latest lover, the Belgian Col. Eduard Willem Baron van der Capellen. The British maintained she spent the time being trained as “Agent AF 44.” at the school for spies in occupied Antwerp, run by the notorious “Red Tiger,” Fräulein Doktor Elsbeth Schragmüller. Schragmüller had acquired a doctorate in political science in 1913 and began the war filtering intercepted communications. She soon moved up to intelligence collection, which led in turn to imparting her knowledge to future German spies. Her reputation for ruthless discipline gained her infamy, though her identity was a secret until long after the end of the war. Mata Hari never mentioned knowing or ever having met Schragmüller. After the war the latter admitted Mata Hari was a German spy, but maintained she never divulged any worthwhile information.

Captain Vladimir de Massloff was a son of Russian aristocracy, just 21 years old—approximately the age Mata Hari’s son would have been, had he lived—and their relationship was a mirror opposite of the ones she usually carried on with older, wealthy men. Part of the reason she agreed to spy, she told her interrogators, was to make “enough money that I never have to deceive Vadime de Massloff with other men.” He is shown here in a photo that may have been taken by Mata Hari herself, and with her in Paris, 1916, when he had been partially blinded at the front by German poison gas. After the war he married, returned to Russia, and vanished in the maelstrom of the Revolution.

“I love officers. I have loved them all my life. I prefer to be the mistress of a poor officer than of a rich banker. It is my greatest pleasure to sleep with them without having to think of money. And, moreover, I like to make comparisons between the different nationalities.”

Capt. Georges Ladoux of the Deuxième Bureau, French military intelligence.

Back in Paris Mata Hari indulged her penchant for uniforms with 21-year-old Capt. Vladimir de Massloff of the Special Imperial Russian Regiment, stationed on the Western Front. Consorting with a Russian would have brought Mata Hari to the attention of French authorities even if she wasn’t a spy. Capt. Georges Ladoux of the Deuxième Bureau, French military intelligence, assumed she was a German agent, but intended to turn her into a spy for France. “Only promise me,” he said, “that you will not seduce any French officers.”

“I ask a million gold francs,” she told him. “I've no intention of hanging around for months getting tidbits of information. I'll bring off one big coup, and then go.” She planned to re-establish contact with German intelligence and work her way up, bed-by-bed, back into the circles of the High Command. “I have already been the mistress of the Crown Prince, and it would be up to me if I wanted to see him again.... Here, I am just a lady of the night; there, I was treated as a queen.”

“Go to Holland,” Ladoux told her, “and you will receive my instructions.”

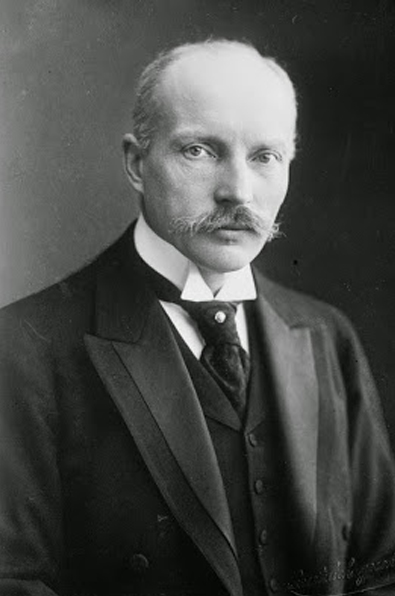

Sir Basil Thomson, Assistant Commissioner of Police and head of Special Branch, Scotland Yard

The British, however, held her ship at Falmouth. This time she was brought to Scotland Yard, where Sir Basil conducted her interrogation. “We were convinced now that she was acting for the Germans,” he wrote, “and that she was then on her way to Germany with information which she had committed to memory.”

Mata Hari admitted she was a spy, but for the French, naming Ladoux as her controller. He told the British he had employed her only as a ruse to entrap her. With a complete lack of evidence, Thomson was compelled to release Mata Hari again—not on her way to Holland, but back to Spain.

Double Agent

Major Arnold Kalle, German military attaché in Berlin’s Madrid embassy. Mata Hari intended to use him. Instead he used her.

Joseph Cyrille Magdelaine Denvignes as a major general

Denied access to Germany, lacking instruction from Ladoux, she targeted the nearest German: Major Arnold Kalle of Berlin’s embassy to Madrid. “I did what a woman does in such circumstances when she wants to make a conquest of a gentleman,” she recalled, “and I soon realized…Kalle was mine.” He let slip that he was sending a U-boat to drop German and Turkish officers in French Morocco to foment an uprising. That night she triumphantly, if thoughtlessly, reported it to Paris in the clear, and at lunch the next day, equally thoughtlessly, to Col. Joseph-Cyrille Denvignes, military attaché with French embassy.

All the while she was playing Kalle, however, he was playing her. The submarine story was fake. He told her the Germans, having broken the French code, knew the sub secret was out. Mata Hari not only allayed his suspicions, she reported the broken code to Denvignes, neglecting to mention that Kalle had advanced her 3,500 francs to spy on the French.

In January 1917 Kalle radioed Berlin that he was working with a spy, code-named H-21. A French listening station atop the Eiffel Tower intercepted the message, which was in a code previously broken by English cryptographers in Room 40 of the Admiralty Ripley building In Whitehall, just down the hall from the office of First Sea Lord Sir John Jellicoe. When the Germans let slip that payment was to be sent to Mata Hari’s maid, by name, at her Netherlands address, the identity of H-21 was revealed. It was all the evidence the French needed to arrest her. It has been claimed that the Germans knew the code was broken, and used it anyway to lure the French into a double-bind: they would either arrest their own agent as a traitor, or continue to use her, allowing Berlin to peddle false information to Paris. In retrospect it seems doubtful the Germans knew the code was cracked, as just two weeks later they used the same cryptography to send the Zimmermann Telegram to Mexico, which provoked the United States into the war—an outcome they surely wished to avoid.

What she didn’t know was that Paris, using a radio listening station atop the Eiffel Tower, had also cracked the German code, but the Germans knew it, and continued using the code to spread disinformation. When transcripts disclosed that Kalle was operating an agent out of Spain, and that payment should be sent to Mata Hari’s Amsterdam address, her fate was sealed. She returned to Paris to find Denvignes avoiding her. Ladoux claimed to know nothing of a Moroccan sub or broken code. De Massloff’s superiors forbade him to continue their affair. On Feb. 13th, Mata Hari was arrested on charges of espionage.

February 13th, 1917

Prisoner

For five months she was held in isolation at Saint-Lazare, the dank, dark Bastille of its day. Investigative Magistrate Pierre Bouchardon of the Ministry of Justice, nicknamed “the Grand Inquisitor,” had already decided her guilt. “From the first interview, I had the intuition that I was in the presence of a person in the pay of our enemies,” he recalled. “...In the pallid light that infiltrated the courtyard of the jail, she did not resemble at all the dancer who had bewitched so many men.... Feline, supple, and artificial, used to gambling everything and anything without scruple, without pity, always ready to devour fortunes, leaving her lovers to blow their brains out, she was a born spy.” (Emphasis in original.)

After months of solitary confinement in squalid conditions, the former sensation of Paris implored Bouchardon, “I cannot stand this life. I would rather hang myself on the bars of my window than live like this.” When Ladoux produced transcripts of the incriminating radio traffic, she admitted taking German money, but protested, “Might it not be possible that the Germans themselves threw French intelligence on a false track...that they are telegraphing only what they want you to know?”

The Prison Saint-Lazare, in the north of Paris

The Prison Saint-Lazare had been converted from a leprosarium at the time of the Reign of Terror in 1793. In the the early nineteenth century it became a women’s prison, dirty and unheated.

After a first night’s stay in a padded cell on suicide watch, Mata Hari, who had lived so luxuriously in her day, dwelt in isolation in the ward known as “La Ménagerie.” for its infestation of rats, lice and fleas. She was reduced to eating nothing but soup and bread, with fifteen minutes of exercise a day and meat once a week. Her only companions were the nuns of the order of Marie-Joseph, who attended the prisoners. Her lawyer, the inffectual Edouard Clunet (an ex-lover) protested the conditions to no avail. Interrogator Capt. Pierre Bouchardon made frequent visits to grill her over and over. For over five months Mata Hari clung to her story that she had been a spy for France, not against it. Appeals from the Dutch government came to nothing. She was still maintaining her innocence when brought to trial on July 24.

In 1935 Saint-Lazare was largely demolished. Only the infirmary and chapel remain, listed as historic monuments since November 2005.

Soupir, France, in May 1917.

While Mata Hari was undergoing interrogation in the prison of Saint-Lazare and being accused of causing the deaths of 50,000 French soldiers, on April 10 French General Robert Nivelle undertook the Second Battle of the Aisne. After a six-day, 5,300-gun artillery bombardment, which served only to alert the Germans of the impending attack, 480,000 French assaulted the Chemins des Dames ridge (background) in the teeth of concentrated machine-gun fire. They suffered 40,000 casualties on the first day alone, 271,000 by April 25th, when the offensive was called off. Nivelle resigned in disgrace. Nearly half the French Army on the Western Front mutinied. At the beginning of June new commander General Philippe Pétain undertook almost 3,500 courts-martial, leading to over 600 death sentences, of which 43 were carried out.

Defeatism threatened France, leading to a purge of the likes not seen since The Terror. At home, over 300 civilians would be shot for espionage, including almost thirty politicians with the temerity to seek peace, and at least two women. Mata Hari, who was not even a French citizen, stood no chance.

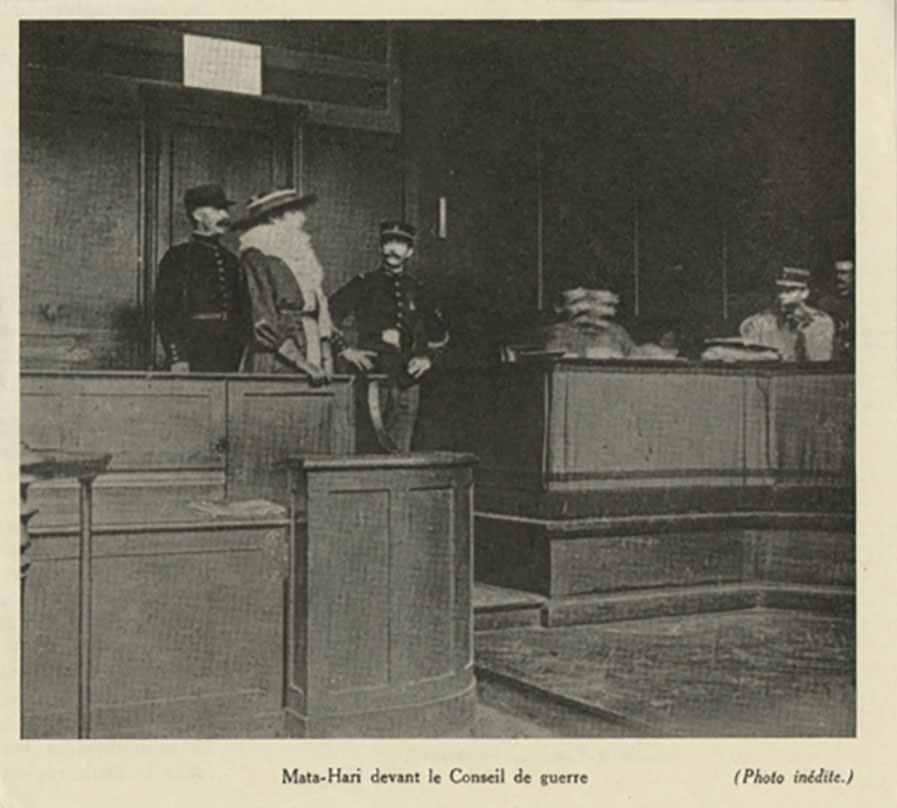

Mata Hari on trial for her life

The trial of The Republic of France vs. Marguérite Gertrude MacLeod-Zelle began on July 24th, 1917 and lasted just two days. Inconvenient evidence, such as the broken code, was ruled a state secret, inadmissible. The prosecution, maintaining that she had sold secrets to the Germans and reported nothing but disinformation, blamed her for the deaths of 50,000 French soldiers. Of proof, prosecutor André Mornet admitted he had “not enough to flog a cat,” but her judges took only 45 minutes to return a verdict of guilty, and sentence her to death. Newspapers reported that Mata Hari exclaimed, “C’est impossible!”

October 15, 1917

By the time she was driven to the cavalry grounds at the Château de Vincennes, at dawn on Oct. 15th, she had come to terms with her fate. Well dressed, composed, she walked unaided to the stake and refused a blindfold. The sergeant-major commanding the firing squad reportedly said, “By God. This lady knows how to die.”

No footage was taken of Mata Hari’s execution. Except for below, internet shots are stills from various movie re-enactments, notably a 1921 French silent and 1964’s Mata Hari, Agent H21 with Jeanne Moreau in the title role (top).

As reported by an eyewitness, British journalist Henry Wales: The first intimation she received that her plea had been denied was when she was led at daybreak from her cell in the Saint-Lazare prison to a waiting automobile and then rushed to the barracks where the firing squad awaited her.

Interrogator Capt. Pierre Bouchardon (left) and prosecutor Capt. André Mornet, looking pleased with themselves on the day of Mata Hari’s execution.

Never once had the iron will of the beautiful woman failed her. Father Arbaux, accompanied by two sisters of charity, Captain Bouchardon, and Maitre Clunet, her lawyer, entered her cell, where she was still sleeping—a calm, untroubled sleep, it was remarked by the turnkeys and trusties.

The sisters gently shook her. She arose and was told that her hour had come.

‘May I write two letters?’ was all she asked.

Consent was given immediately by Captain Bouchardon, and pen, ink, paper, and envelopes were given to her.

She seated herself at the edge of the bed and wrote the letters with feverish haste. She handed them over to the custody of her lawyer.

Then she drew on her stockings, black, silken, filmy things, grotesque in the circumstances. She placed her high-heeled slippers on her feet and tied the silken ribbons over her insteps.

She arose and took the long black velvet cloak, edged around the bottom with fur and with a huge square fur collar hanging down the back, from a hook over the head of her bed. She placed this cloak over the heavy silk kimono which she had been wearing over her nightdress.

Her wealth of black hair was still coiled about her head in braids. She put on a large, flapping black felt hat with a black silk ribbon and bow. Slowly and indifferently, it seemed, she pulled on a pair of black kid gloves. Then she said calmly:

‘I am ready.’

The party slowly filed out of her cell to the waiting automobile.

The car sped through the heart of the sleeping city. It was scarcely half-past five in the morning and the sun was not yet fully up.

Clear across Paris the car whirled to the Caserne de Vincennes, the barracks of the old fort which the Germans stormed in 1870.

Actual photo of troops and observers at Mata Hari’s execution. She does not appear to be visible. Firing squad is lined up at right.

The troops were already drawn up for the execution. The twelve Zouaves, forming the firing squad, stood in line, their rifles at ease. A subofficer stood behind them, sword drawn.

The automobile stopped, and the party descended, Mata Hari last. The party walked straight to the spot, where a little hummock of earth reared itself seven or eight feet high and afforded a background for such bullets as might miss the human target.

As Father Arbaux spoke with the condemned woman, a French officer approached, carrying a white cloth.

‘The blindfold,’ he whispered to the nuns who stood there and handed it to them.

‘Must I wear that?’ asked Mata Hari, turning to her lawyer, as her eyes glimpsed the blindfold.

Maitre Clunet turned interrogatively to the French officer.

‘If Madame prefers not, it makes no difference,’ replied the officer, hurriedly turning away.

Mata Hari was not bound and she was not blindfolded. She stood gazing steadfastly at her executioners, when the priest, the nuns, and her lawyer stepped away from her.

The officer in command of the firing squad, who had been watching his men like a hawk that none might examine his rifle and try to find out whether he was destined to fire the blank cartridge which was in the breech of one rifle, seemed relieved that the business would soon be over.

A sharp, crackling command and the file of twelve men assumed rigid positions at attention. Another command, and their rifles were at their shoulders; each man gazed down his barrel at the breast of the women which was the target.

She did not move a muscle.

The underofficer in charge had moved to a position where from the corners of their eyes they could see him. His sword was extended in the air.

It dropped. The sun—by this time up—flashed on the burnished blade as it described an arc in falling. Simultaneously the sound of the volley rang out. Flame and a tiny puff of greyish smoke issued from the muzzle of each rifle. Automatically the men dropped their arms.

At the report Mata Hari fell. She did not die as actors and moving picture stars would have us believe that people die when they are shot. She did not throw up her hands nor did she plunge straight forward or straight back.

Instead she seemed to collapse. Slowly, inertly, she settled to her knees, her head up always, and without the slightest change of expression on her face. For the fraction of a second it seemed she tottered there, on her knees, gazing directly at those who had taken her life. Then she fell backward, bending at the waist, with her legs doubled up beneath her. She lay prone, motionless, with her face turned towards the sky.

A non-commissioned officer, who accompanied a lieutenant, drew his revolver from the big, black holster strapped about his waist. Bending over, he placed the muzzle of the revolver almost—but not quite—against the left temple of the spy. He pulled the trigger, and the bullet tore into the brain of the woman.

Mata Hari was surely dead.

On the command to fire, one of the riflemen fainted. Eleven bullets struck Mata Hari, one through the heart. Her body, unclaimed, was donated to the department of medicine at the University of Paris, lost to history.

In another twist, both Ladoux and Denvignes were soon arrested for espionage. Both were ultimately released for reasons unexplained. Had they betrayed Mata Hari to Berlin? Did they use her to divert attention from their own treachery? Or were they all caught up in German-induced spy fever? The truth will never be known. Usually portrayed as a femme fatale or innocent dupe, Mata Hari was neither. She used her skills of seduction on men of opposing sides, and was ultimately betrayed by both. Mornet called her “the greatest woman spy of the century.” That may not have been true then, but a hundred years later there remain none more famous than Mata Hari.

Colorization by klimbims

More from Don Hollway:

|