The Valkyries fetch the spirits of the slain

in Åasgåardsreien by Peter Nicolai Arbo

At Cl0ntarf, 0n G00d Friday a th0usand years ag0, the Irish united under High King Brian B0ru t0 expel the Vikings fr0m Erin.

|

By D0n h0llway as appeared in HISTORY MAGAZINE, Feb/march 2014

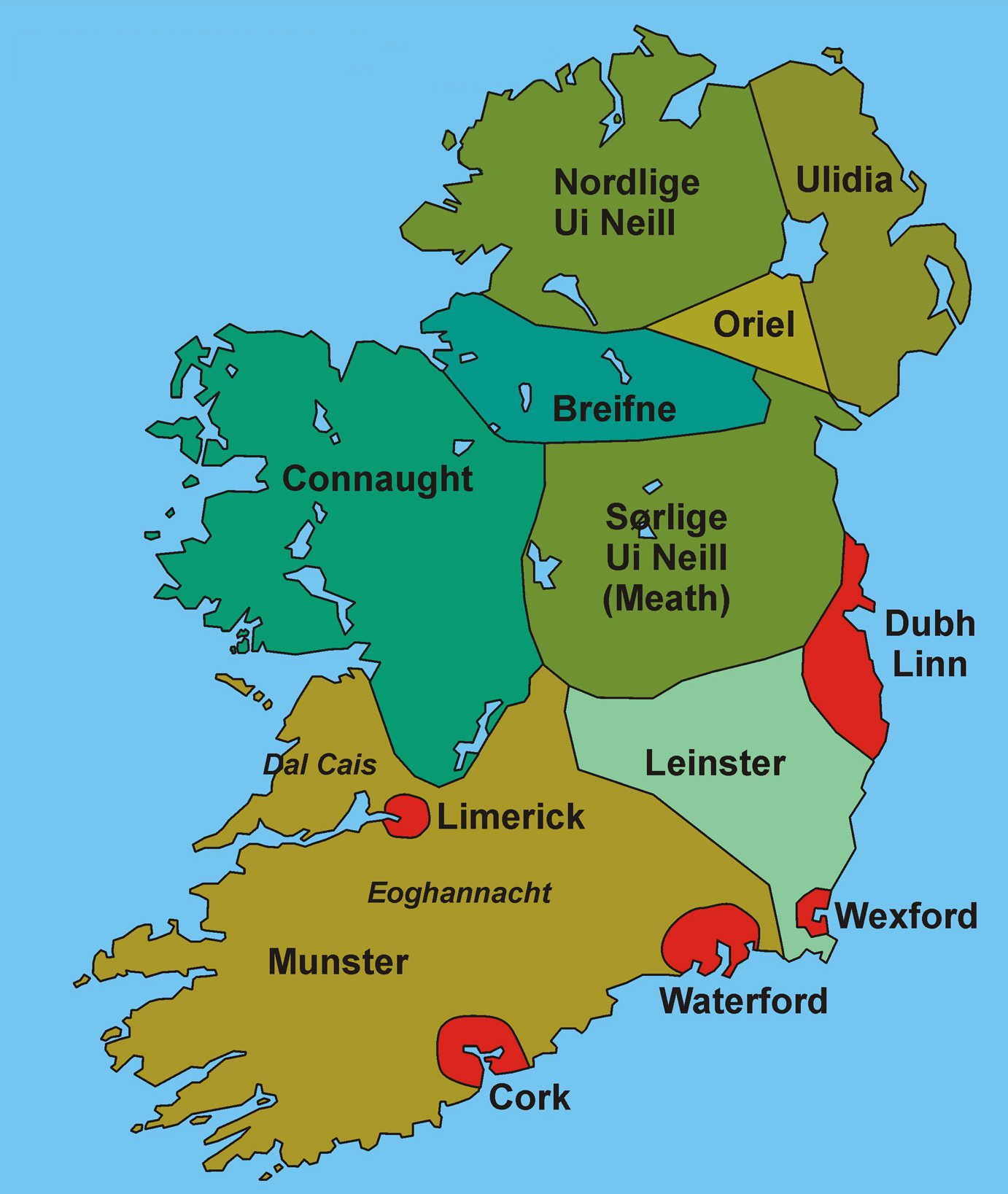

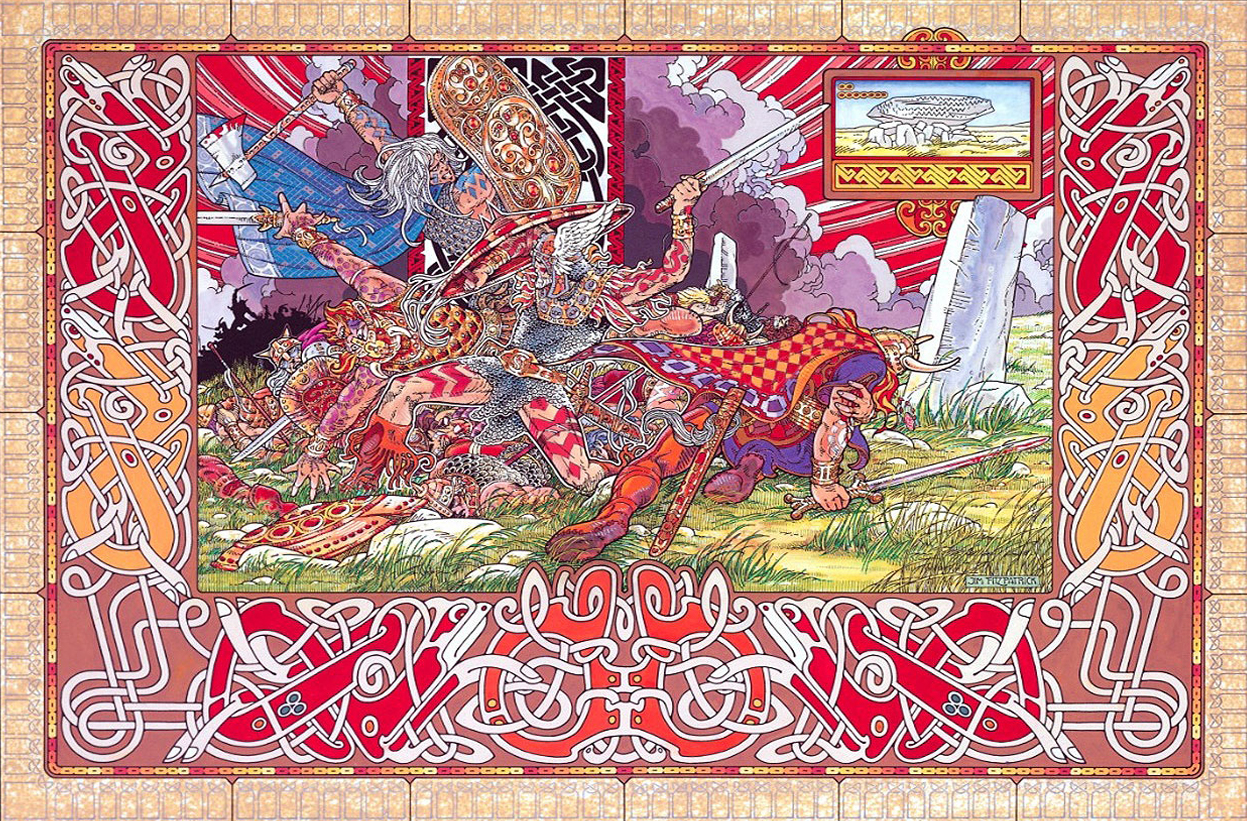

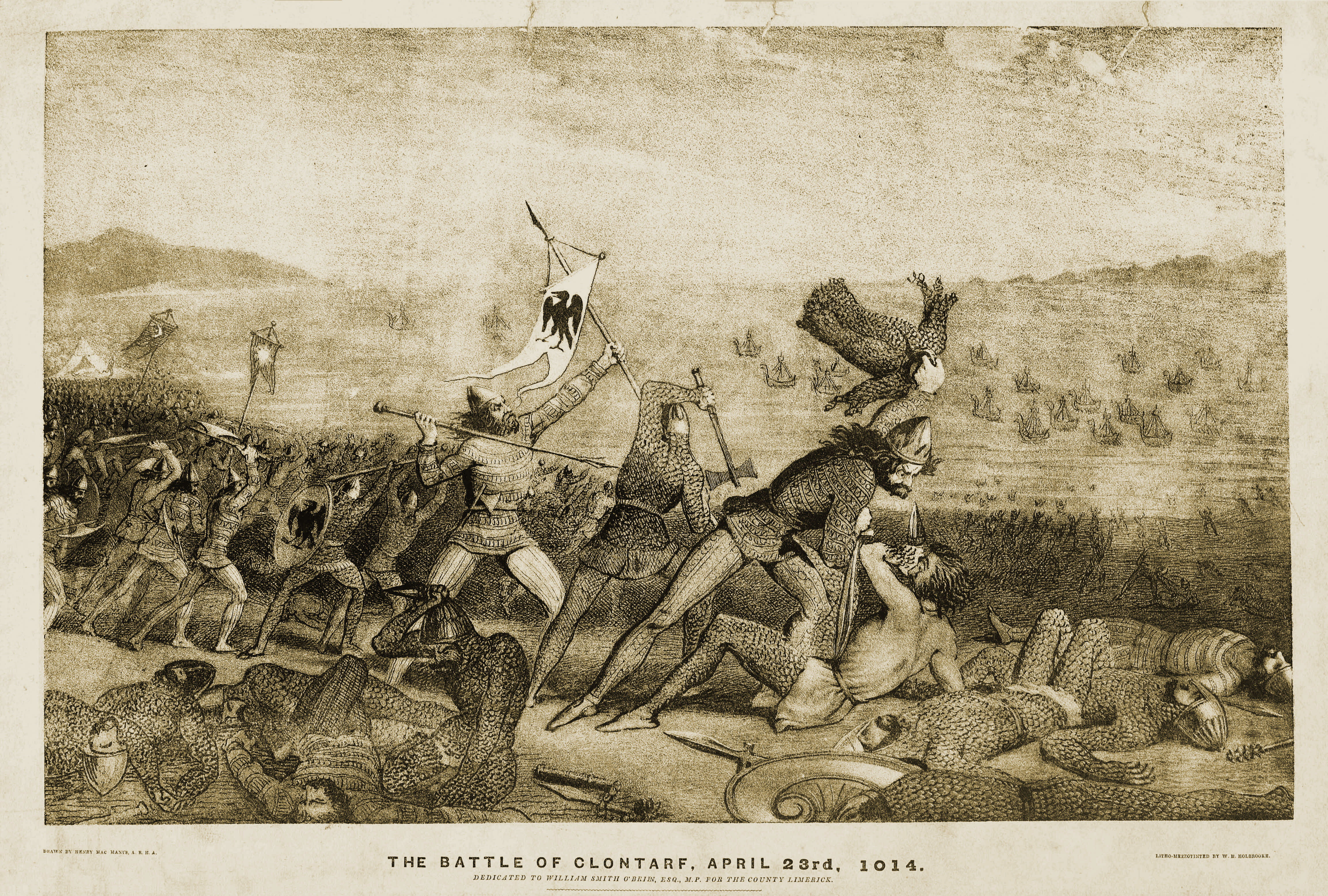

t has been called “the reaping of kings, the garnering of chiefs like a harvest,” but all we know of the Battle of Clontarf in 1014 AD derives from a few oft-conflicting Norse sagas and Irish chronicles. War pipes keen, Valkyries ride, banshees wail, Norns weave men’s fates on a mystic loom and old gods battle the new. Panegyric, bombastic, hyperbolic, Homeric…but just as the Iliad bore hidden truths, the old tales bear retelling, with one medieval caveat: “The full events and exploits of that battle are known to God alone; for everyone else who was acquainted with them fell there together.” Over 200 years the Norse had never conquered the Emerald Isle, a patchwork of over 150 warring tribes, clans and petty kingdoms that could not be felled in a stroke. The Norwegians, and later the Danes, settled for taking Irish girls to wife and making sporadic raids into the interior from their strongholds on the coast. The strongest of these was Dublin (from the Gaelic Dubh Linn, “black pool,” for the muddy backwater where the rivers Liffey and Poddle meet before emptying into the crescent-shaped harbor). Its ruler, King Sigtrygg II Silkbeard Olafsson, like most Vikings of his time and place, was half-Irish. But to the Gaels the Scandinavians were still the Gaill, foreigners, and they yearned for a King of Kings to lead them against the common foe. High King 0f the Emerald Isle Yet they could only be united by force. Brian Boru (Brian Bóruma mac Cennétig, in modern Irish Brian Boroimhe), started out as one of twelve sons of a chief of the Dalcassians (Dal gCais), a minor tribe from the far west, near Limerick. Over the span of three generations he rose to conquer Munster in the south, Connacht in the north and, in the east, Leinster, ruled by Sitrygg’s uncle, Máel Morda mac Murchadha. In 999, those two rose up against Brian. With the help of Malachy II the Great (Máel S Sechnaill mac Domnaill), King of Meath and High King of Ireland, Brian defeated them at the battle of Glenn Máma and sacked Dublin. Just three years later, however, Brian repaid Malachy by forcing him to surrender the high throne. His usurpation can be somewhat forgiven as he brought Ireland peace. It was said a lone woman could walk the length of the Emerald Isle with a gold ring, unmolested. As High King, Emperor of the Irish, Brian built roads and bridges, encouraged learning, and enforced justice. He generously let Malachy, Máel Morda and Sigtrygg sit their thrones, even though all three harbored grudges against him. He married his daughter Sláine to Sigtryyg and took for himself as queen Malachy’s former wife, Máel Morda’s sister and Sigtrygg’s mother, the notorious Gormflaith.

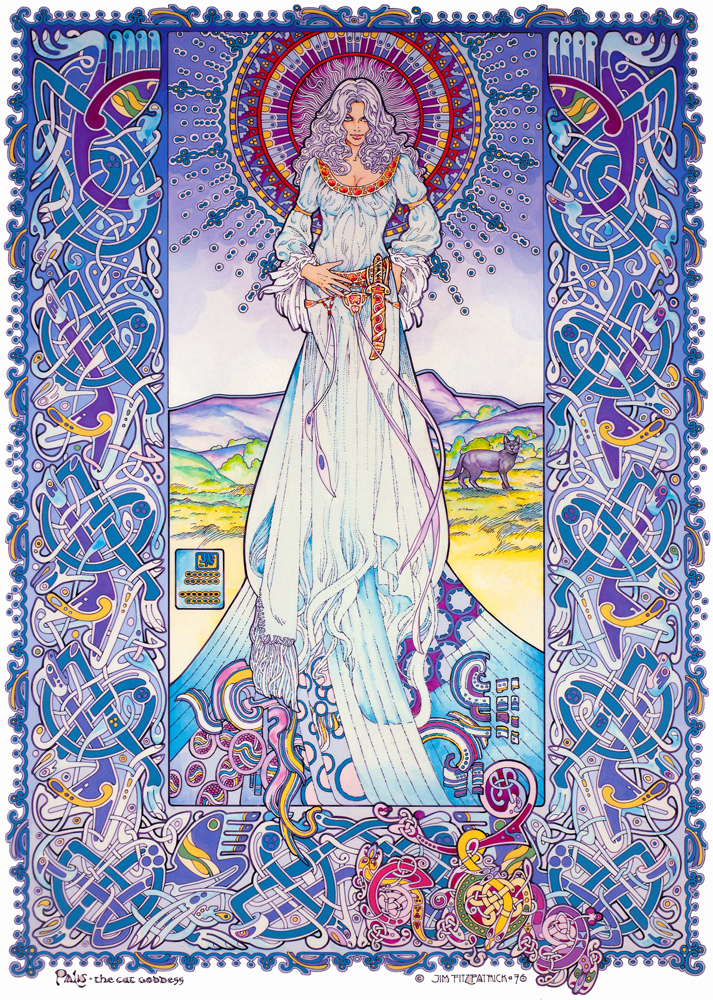

The M0rrígan THE W0MAN BEHIND THE WAR Far from fighting over Gormflaith, they likely wished themselves well rid of her, for she was the very incarnation of the Morrígan, the Irish goddess of war. A renowned beauty, she held sway over men and used it mercilessly to her own ends.

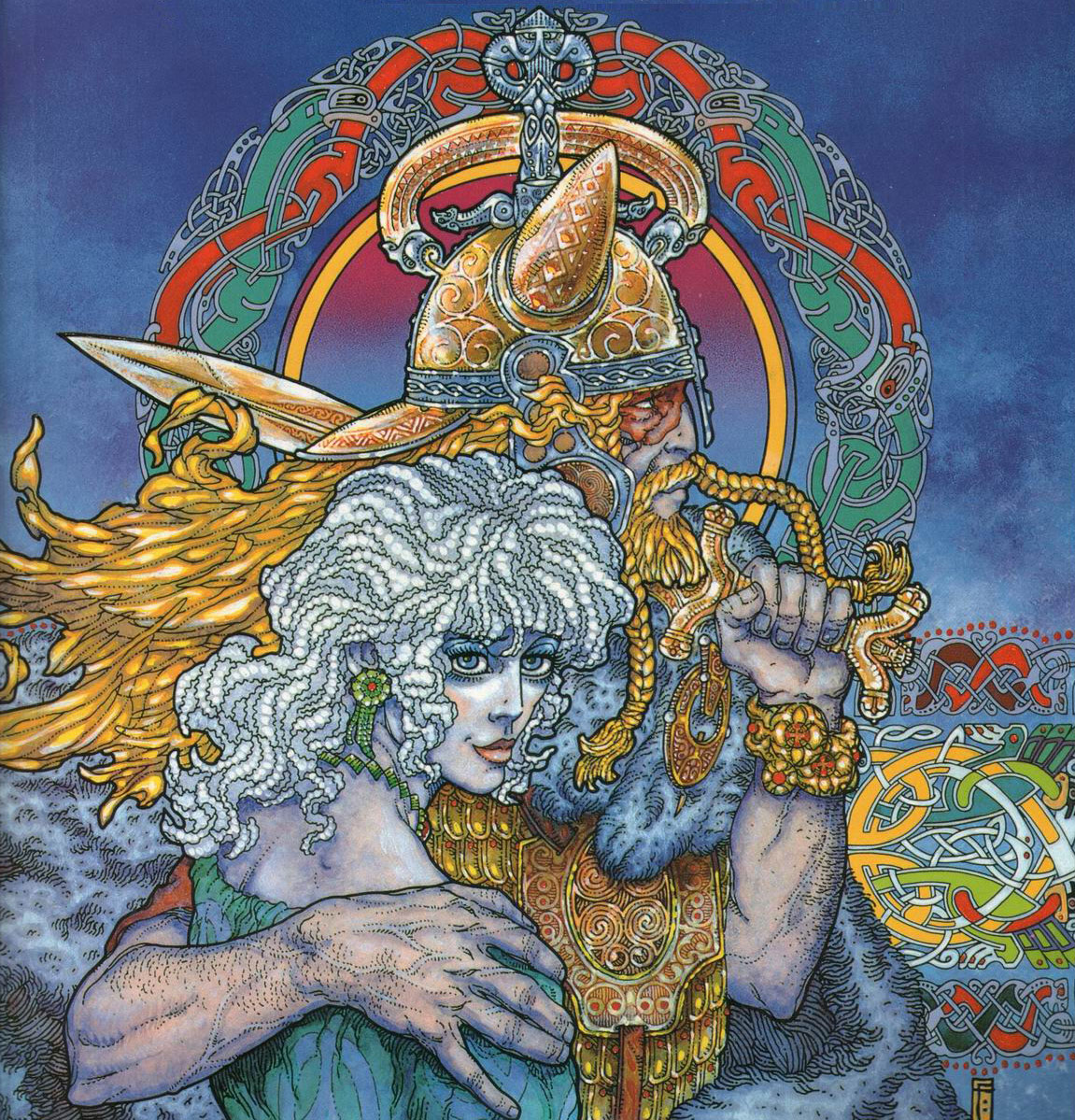

The Norse called her Kormlada, “… the fairest of all women [but] she did all things ill over which she had any power.” The daughter of Murchadh mac Finn, King of Leinster, and widow of Olaf Cuarán, King of Dublin, mother of Sigtrygg, sister of Máel Morda and wife to both Malachy and Brian, she was accustomed to power and a constant schemer in keeping it. When Sigtrygg’s father Olaf died suddenly, she took up with Malachy while he was High King, but they parted when he bent knee to Brian. When Brian passed over their son Donnchadh and chose as his heir Murchadh, son of his first wife, Mor, Gormflaith broke with him, taking refuge with Sigtrygg in Dublin to plot her revenge. Donnchadh notably sided with Brian, but Máel Morda needed little goading against the high king. At court Gormflaith burned a silk coat given him by Brian, scorning him for having accepting it. Then, quarrelling over chess, Murchadh mortally insulted Máel Morda. (After the defeat at Glen Mama, Máel Morda had been found hiding in a yew tree; Murchadh advised him that if he sided with the Vikings again, he should find another.) Máel Morda left Brian’s court in a rage, without permission. When Brian summoned him to answer for this, Máel Morda killed the messenger. It was war again, Máel Morda and Sigtrygg against Malachy, Murchadh and Brian. THE CLASH OF CIVILIZATIONS It is primarily due to Gormflaith’s machinations that Clontarf gained renown as the climax of the Cogad Gaáedel re Gallaib, the War of the Irish with the Foreigners. Not wanting a repeat of the disaster at Glen Máma, and knowing this time Brian would not again be so magnanimous in victory, she and Máel Morda spurred Sigtrygg to call on all the greatest Vikings of the age. To aid the Vikings of Dublin and the Irish of Leinster came fighting men of the Norwegians, Danes, Britons, men of Cornwall, Wales, Normandy and Francia, of the Hebrides and of Lochlann (Scotland). Sigtrygg sailed to gain support of Sigurd Hlodvirsson the Stout, Jarl (Earl) of the Orkney Islands and northern Scotland, offering not only Brian’s throne of Erin, but Gormflaith’s hand in marriage. Over the objections of his men, Sigurd accepted.

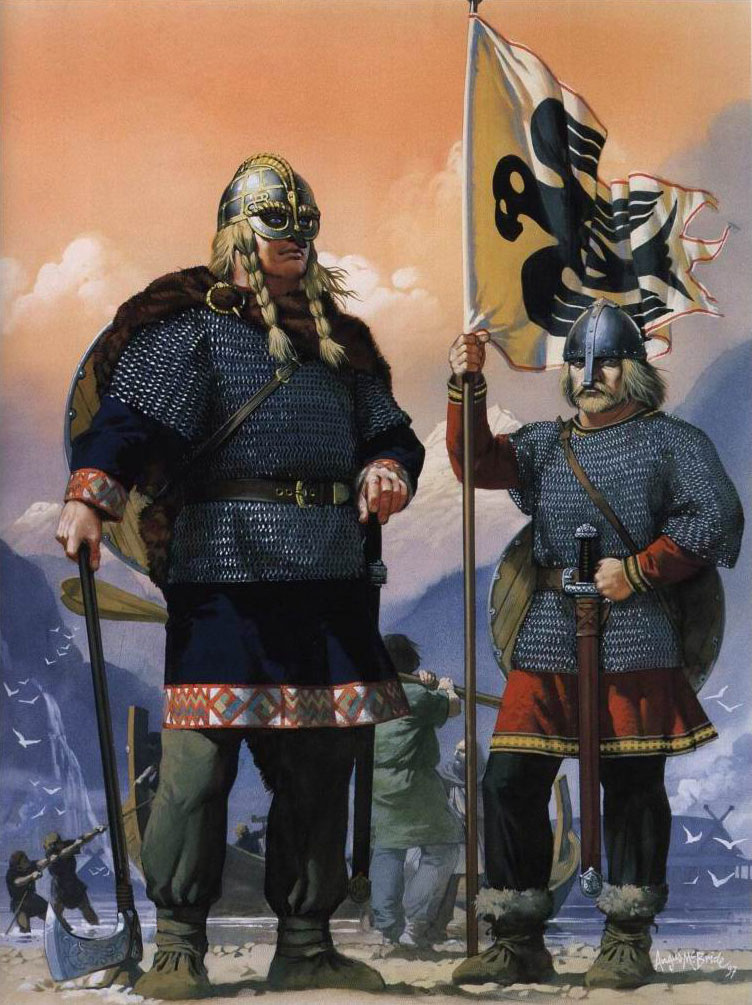

Br0dir and Óspak of Man Gormflaith then sent Sigtrygg to the Isle of Man, ruled by Danish brothers Brodir and Óspak, “men of such hardihood that nothing can withstand them.” Gormflaith told Sigtrygg to “spare nothing to get them into thy quarrel, whatever price they ask.” Sigtrygg made Brodir the same offer he’d made to Sigurd, on the condition it was kept secret. Brodir accepted. Once a consecrated Christian, he had rejected the faith and become, as one Norse saga claimed, “God’s dastard, and now worshipped heathen fiends, and he was of all men most skilled in sorcery.” He was said to wear his black hair so long he kept it tucked in his belt, and magic armor “on which no steel would bite.” Óspak, also a heathen but according to one Norse saga “the wisest of all men,” declared “he would not fight against so good a king” as Brian. Brodir, with his fleet of 20 longships, attempted to blockade him, but Óspak and his two sons broke through with ten ships and sailed around Ireland to link up with Brian, take baptism and swear fealty. To battle the foreigners, Brian summoned all his sons and kinsmen, as well as the lesser kings of Erin, the loyal Vikings of Limerick and the south, the fighting men of Munster and Meath, and the greatest champions of the Gaels from Ireland and Scotland. Their names read like a roll call of great Irish families: O’Reilly and O’Rourke, O’Farrell, O’Kelly and O’Quinn, O’Donnell and O’Heyne, Kennedy and Phelan. They were to converge on Dublin the week before Palm Sunday. In decades and centuries to come the battle to come would be seen not be so much a clash of civilizations, for there would be Irish and Norse fighting on both sides, for the Norse in Brian’s army had for the most part been born in Ireland, married Irish girls and spoke Gaelic. but as a battle of good vs. evil: pious Brian leading the followers of the white Christ against pagan Sigtrygg and the sons of Odin, a heathen horde with “no reverence, veneration, respect or mercy for God or for man, for church or for sanctuary.” It would be Ireland’s Troy, an Armageddon, a Ragnarok, an end of days. And thus it would prove for many thousands who fought there. TREACHERY Brian and his forces laid waste to the Dublin surrounds and camped on the plain of Clontarf (Cluain Tarbh, “meadow of the bull,” probably Dublin’s cattle pasture), from where they could see the walls of the city glittering with Viking helmets and the bay of Dublin bristling with the dragon-prows of their longships.

The Irish bef0re the walls 0f Dublin From the walls of Dublin the foreigners could see the countryside burning, but could only reach Brian by way of Dubhgall’s (“Black Foreigner’s”) Bridge over the River Liffey, easily blocked. In the city, the Viking laid plans. Brodir, according to the sagas, discerned the outcome of battle through sorcery: If the two sides fought prior to Good Friday, April 23, all Brian’s enemies would fall; if they fought on Good Friday, Brian would still be victorious, but himself fall. With a choice of death or mere defeat, Brodir determined to force battle on Good Friday. “On the fifth day of the week a man rode up to Kormlada and her company,” an Icelandic saga relates, “…he talked long with them.” That the secretive conversation seemed worthy of mention suggests it was of import. That same day, Holy Thursday, a Viking delegation promised Brian that if he would delay the fight until morning, they would sail away. Pious Brian was loath to fight on a fast day. He called a great war council, including Malachy and Murchadh and the lords of Connaught, Munster and Meath. It was at this point, however, that Malachy repaid Brian for usurping his throne, refusing to fight at all and withdrawing with his men to await the outcome. Had Malachy sent the rider to Gormflaith, his ex-wife, to strike a devil’s bargain? Irish chroniclers, particularly those disposed toward Brian, certainly accused him ever after of treachery: “…if he would not attack the foreigners, the foreigners would not attack him; and so it was done, for the evil understanding was between them.” The desertion of Meath was more the loss since Brian had sent Donnchad off with his men, ostensibly to lay waste to Leinster, but realistically to keep him from going over to his mother and half-brother in Dublin. With his forces weakened Brian must have been relieved, as night fell, to see the Vikings board their ships, set sail and depart for home. It was a ruse. When the sun came up on Good Friday the dragon ships had returned, this time beached on the harbor’s north shore. The Viking horde had landed on the plain of Clontarf.

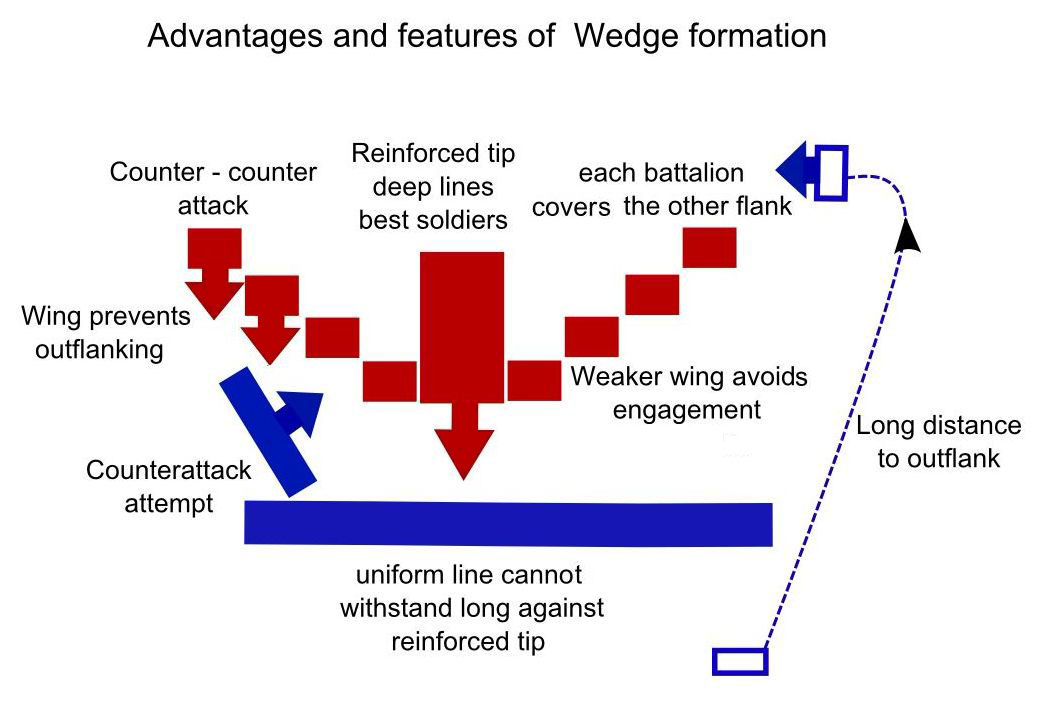

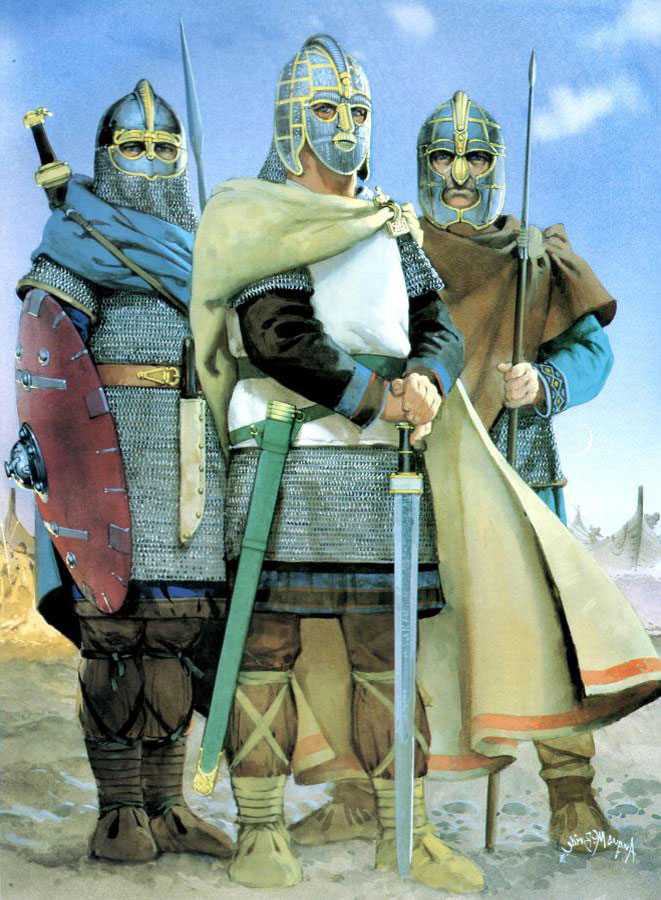

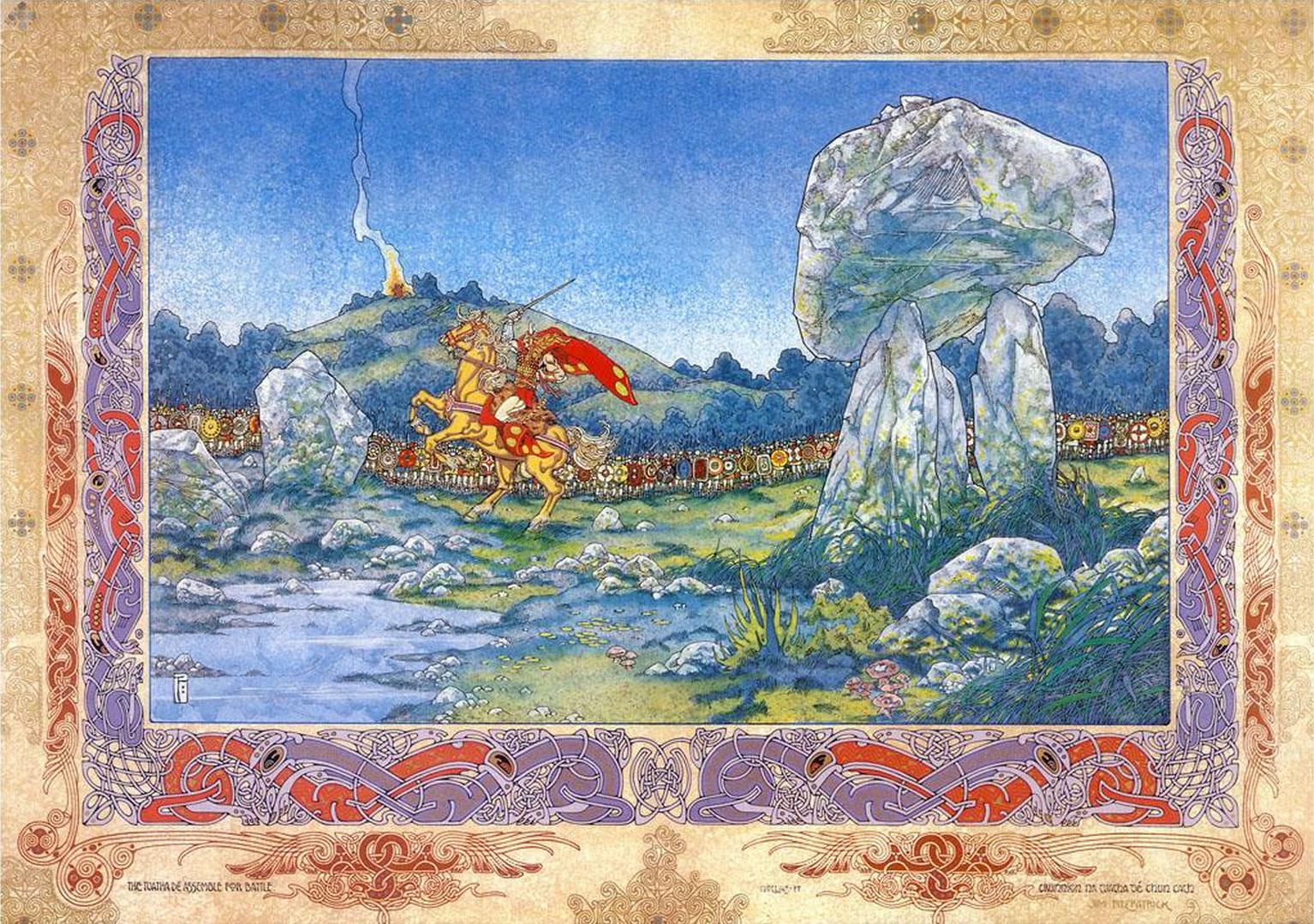

The Viking ruse DAWN OF BATTLE And so the two great hosts girded for battle. Troop estimates vary widely, from a realistic 5,000 total to an epic 20,000 on each side. They drew up facing each other east-west, with Dublin Bay to the south and on the north a forest, Tomar’s Wood. Though none of the accounts explicitly say so, it’s reasonable to assume the Norse, facing east, probably formed up in their customary wedge formation—the svinfylking, the “boar snout”—behind a shield-burg, a wall of shields, with their leaders on point: Sigurd of Orkney with his retainers Thorstein, Asmund the White and Hrafn the Red, under Sigurd’s raven banner, symbolic of Odin, woven by his mother and said to bring victory to Sigurd, but death to whomever carried it; Brodir of Man to one side with his mail armor “on which no steel would bite”; and also Anrad, grandson of the King of Lochlann, “the head of valour and bravery of the army.” Dubghall, Sigtrygg’s grandson, commanded the Dublin Danes behind them. (Though Norse sagas claim Sigtrygg took the field, Irish writers maintain he watched the battle from the battlements of Dublin with the women, Gormflaith and Sláine.) At least two thousand of the Vikings wore knee-length hauberks of layered chain mail. None wore the horned or winged helmets, as Victorian romantics would have it. Their main weapons were their swords, to which they gave names and sang songs of their exploits, but the Danes also favored the two-handed battle-axe, with which a skilled man could behead a horse or split its rider to the saddle. Both sides rode, but only to battle; there was then no such thing as cavalry in Ireland. The fighting would be man to man. Máel Morda and his Leinstermen took position behind the Vikings. Perhaps because they could ill afford it, most Irish spurned metal armor as unmanly. The kerns, their light infantry, wore leather armor and used swords, but their weapon of choice was the spear: the heavy thrusting lance-think of it as a dagger with extra reach-and the light throwing javelin, essentially an oversized arrow stabilized with feather or leather fletching or cloth streamers, said to make an banshee-like wail as it flew. It seems only the Dalcassians made use of the “Lochlann axe.” Irish chronicles have them arrayed in three ranks. Óspak led one flank, his two sons at his side. Brian’s brother Ulf Hroda (possibly a stepson, as his name is very Norse; the Vikings called him “Wolf the Quarrelsome”) led the other; and in the center, the fighting men of Desmond under their king, Brian’s grandson Conaing, joined the Dalcassians under his uncle Murchadh. (A Viking saga claims a foster-son of Brian, Kerthialfad, led the Irish; they may have been the same person.)

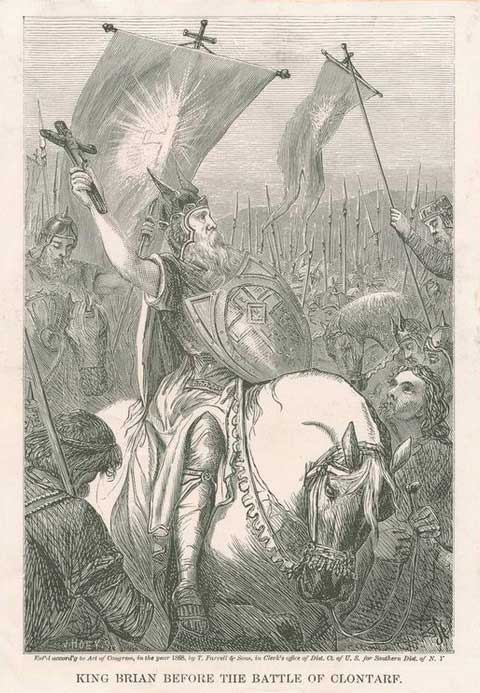

Aibhell, banshee 0f the Dalcassians Acclaimed Ireland’s greatest warrior, Murchadh fought with a sword in each hand, and his son Turlogh and his warrior-saint friend Dunlang O’Hartigan (Dubhlainn Ua Artigan) at his side. Seemingly alone among the Irish, and perhaps to his shame, Dunlang wore a cloak said to be given him by Aibell, the banshee of the Dalcassians, through which he could not be seen—possibly a reference to armor. Yet Dunlang had seen a vision of paradise and foretold all their deaths that day. “This is not good encouragement to fight,” Murchadh said, “and if we had such news we would not have told it to thee.” Some accounts accuse Murchadh of leading too far out in front, possibly in a Viking-like wedge formation. Domnhall, son of Emin, the mormaer or High Steward of Mar in Scotland, advised, “Thy countenance is bad, O royal champion, though thy courage is great.” Murchadh replied that he was no false hero to leave his share of glory on the field, and Domnhall answered in kind. Malachy and his men stood off to one side, awaiting the outcome, and no one knows the thoughts going through the mind of the King of Meath. Brian rode before his men, their “three score and ten banners” waving, with a crucifix held high, reminding one and all their Lord had died for them on this day, a thousand years past. The elderly king would not take part in the battle but instead retired to his tent behind the Irish lines, where the sons of Erin would have to run over him if they fled. There, behind his own shield wall, he resigned himself to prayer, confiding to his retainers that Aibell had visited him in the night as well, and told him he would not survive the day. FIRST BL00D The Battle of Clontarf would be no contest of strategy or maneuver, but comprised of a thousand individual combats, in which victory went to the man most skilled with a blade, or who refused to give or take quarter, or who simply bled to death last. The previous night, possibly as part of the devious delegation, Plaitt, prince of Lochlann, had asserted that no man of Erin could stand against him. But Domhnall of Mar was no Irishman. He had accepted the challenge. Now Plaitt called, “Where is Domhnall?”

Plaitt, Prince of L0chlann, claimed n0 man of Erin c0uld stand against him: “Where is D0mhnall?” “Here, thou reptile,” answered Domhnall, striding forward. Perhaps nursing some old clan grudge, these two Scots did single combat between the armies, the result boding ill portent for the outcome as a whole: according to an Irish account, they perished “…with the sword of each through the heart of the other, and the hair of each clinched in the hand of the other.” The two Scots had come a long way to die in Ireland.

“They died with the sw0rd of each thr0ugh the heart of the 0ther, and the hair 0f each clinched in the hand of the 0ther.” The Gáedel and the Gallaib Who charged first is unknown, but a svinfylking’s strength was in attack. The noise must have been stupendous, though anyone a mile or so away might never have known a battle was taking place. From behind the Viking throng, Máel Morda’s javelin men would have been at a disadvantage, having to throw over their allies’ heads into the wide-flung enemy lines, but Murchadhs’ Dalcassians and Conaing’s Desmonders had no such problem. Irish javelins wailed over the ground between the hosts, piecing shield and mail in the Danish ranks, and while the Vikings were still shuddering under the impact the Dalcassians and Munstermen hurled themselves upon them.

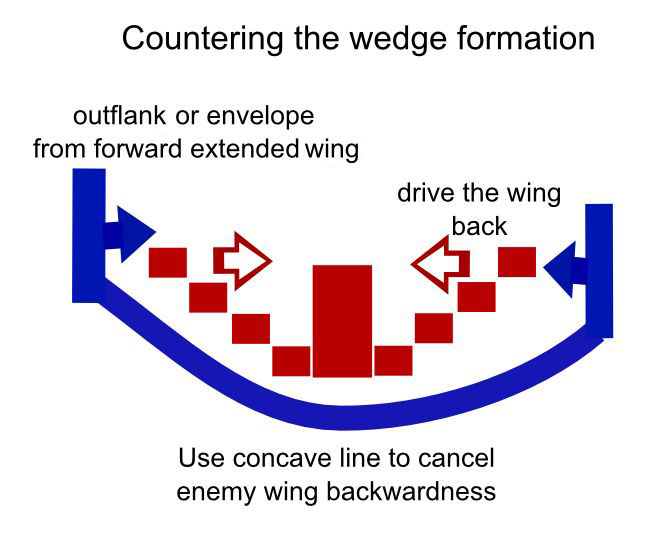

a svinfylking’s strength was in attack Protecting Murchadh, Dunlang singled out one of the Danish champions, ran a spear through him and took his head. But the Vikings swarmed over him. Murchadh, looking around, could hear him calling out where the Danes were falling. “That voice is the voice, and these are surely the blows, of Dunlang O’Hartigan, but I cannot see him!” Shamed, Dunlang threw off his cloak, or armor, and was immediately struck down. But on the north flank a thousand of the rebellious Leinstermen carried the fight to the O’Brians, O’Rourkes, and O’Farrells. “These parties were equally matched,” says an Irish account, “…they very nearly killed each other altogether.” Óspak received a severe wound. Both his sons were killed. Brodir hacked his way through the Irish, his armor shrugging off all blows. Standing on the sidelines, Malachy would later recall, “I never saw a battle like it, nor have I heard of its equal; and even if an angel of God attempted its description, I doubt he could give it.” He and his men found themselves flecked with droplets of blood carried on the wind blowing over the battle. In his tent behind the lines, Brian paused in his prayers to ask his attendant, Latean, how went the battle, and particularly Murchadh’s flag. Latean said, “It is standing, and many of the banners of the Dalcassians around it, and many heads are falling around it.” In the center, the Desmonders had followed hard-charging Murchadh to their cost. Almost all were slain. Their king Conaing cut his way through to Máel Morda himself. Some sixteen men died trying to keep them apart, but in vain. The two kings slew each other on the spot. Watching from the walls of Dublin, Sigtrygg is said to have remarked, “Well do the foreigners [Vikings] reap the field, many is the sheaf they cast from them.” His wife, Brian’s daughter Sláine, replied only, “The result will be seen at the end of the day.” BL00DY STAND0FF She spoke true. The Battle of Clontarf is said to have lasted all day, sunup to sundown. No man could swing an axe or heavy sword for more than a few minutes at a time, and as they were not so well organized as to have rotated fresh troops to the fore in the Roman manner, we can assume the battle had several pauses in which men caught their breath, though such instances were of little note to the chroniclers. Nor was any thought given to strategy. None seem to have realized that the Viking svinfylking, so effective against a line of foot soldiers, was vulnerable to flanking attacks and to missile weapons, offering a compact, can’t-miss target to Irish javelins. The men in the center, probably so closed-packed they could neither run nor raise their shields for shelter, could only stand and die. Once the Gaels closed on both sides to launch their spears, they almost inadvertently achieved the Holy Grail of classical warfare: the double envelopment. On the north, only a hundred of Brian’s men survived, but they pursued the remaining Leinstermen into Tomar’s Wood, caught their leader and beheaded him, too. On the Irish left, though their swords and axes took a fearsome toll, the Viking shield wall was chipped away by the spears of Connaught. Like a city wall, once the shieldburg was broken, the enemy poured through the gaps, for the core had been shattered. Armor could not help any Dane who found himself surrounded by wolfish Gaels. “That was the decisive defeat that took place on the plain,” claim the chronicles, “for they were [almost] all killed.”

“That was the decisive defeat that t00k place 0n the plain, f0r they were [alm0st] all killed.” Brodir came up against Ulf the Quarrelsome, who struck him down three times. Realizing his mail might not be pierced, but that he might well be beaten to death inside it, Brodir fled into Tomar’s Wood. Brian’s attendant reported, “The greater part of the hosts on either side are fallen, and those who are alive are so covered with spatterings of the crimson blood…that a father could not know his son from any of them,” but that Murchadh’s flag had passed through the enemy ranks. Brian said, “The men of Erin shall be well while that standard remains standing, because their courage and valor shall remain in them all, as long as they can see that standard.” The surviving Norse fled for the dimskilling, the sand dunes where their ships lay beached. On the walls of Dublin it was Sláine’s turn to rejoice: “The foreigners are going into the sea, their natural inheritance.” Sigtrygg hit her in the mouth, knocking out one of her teeth. TIDE 0F DESTINY Yet the sea-rovers now found their ruse had backfired. The battle had gone on so long that the tide had come back in. Astronomers have calculated that an unusually high neap tide rolled into Dublin Bay that evening; the Vikings’ dragon ships had been floated off the beach and carried out to sea. Now their heavy armor was a detriment, too; unable to swim for it, they could only turn at bay.

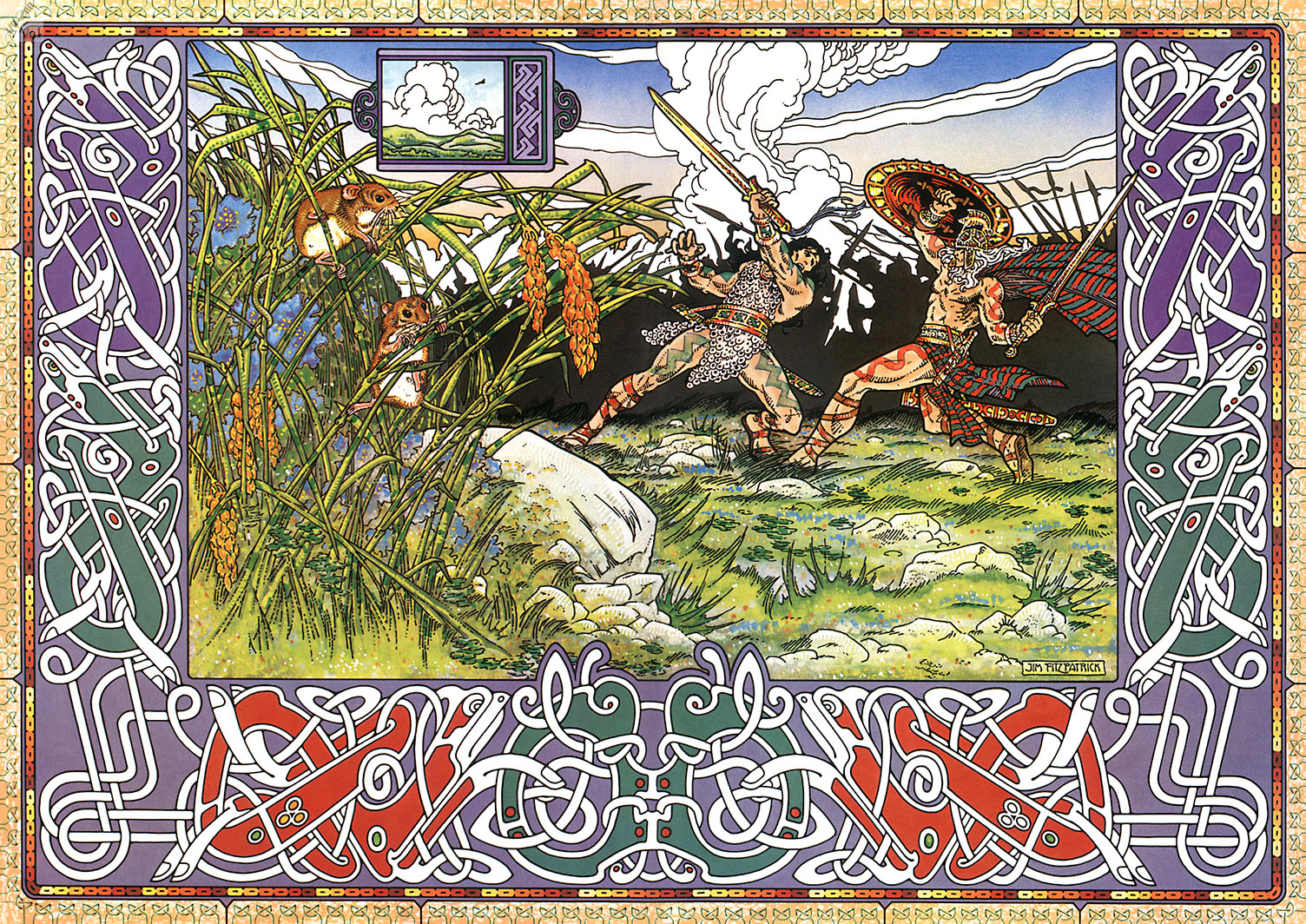

The N0RTHMEN turn at bay It was here that Murchadh, sword in each hand, cornered Jarl Sigurd the Stout of Orkney under his raven standard which ever brought victory to him, but death to its bearers. True to the legend, Murchadh slew the bearer first. In one of the most famous scenes of all the sagas, Sigurd called upon his bodyguard Thorstein to take up the flag, but Asmund the White warned, “Don’t bear the banner! For all they who bear it get their death.” “Hrafn the Red!” called Sigurd. “Bear thou the banner.” Hrafn would have none of it: “Bear thine own devil thyself.” “’Tis fittest that the beggar should bear the bag,” said Sigurd, tucking the banner into his tunic. But its spell was broken. Murchadh dealt Sigurd a right-handed blow that knocked off his helmet, and then a left-handed blow that cut deep into his neck. Sigurd fell dead, and soon Asmund with him. But the day-long strife had taken its toll of the Irish champion as well. He had one sword left when against Anrad of Lochlann counterattacked, driving the Irish before him. Murchadh came to the rescue, but Anrad “cleft his hand, tearing the fork of his fist.” Murchadh dropped his other sword as well. The two men grappled. Murchadh managed to grab the back of Anrad’s hauberk and strip it over his head. The two men went down grabbing at each other’s weapons. Murchadh got Anrad under him, took the Viking’s own sword and ran it through him into the ground three times. Dying, Anrad drew his knife and slashed open Murchadh’s leather-clad stomach, spilling his entrails.

Murchadh 0f Ireland and Anrad 0f L0chlann battle t0 the death The Tolka is neither as large nor as fast as the Liffey. (Some historians have placed the battle between the rivers, with the Danes trapped on the point, but there is little doubt it was fought north of the Tolka.) The last hundred Connaughters caught the last twenty Danes trying to escape across Dubghall’s Bridge over the Liffey. Turlogh, son of Murchadh, was last seen chasing several Danes into the water near the weir (fishing dam); his drowned body was found later with his fingers still entwined in their hair. Hrafn the Red fled into the Liffey but felt himself being dragged down. Having made two pilgrimages to Rome, he called on the Apostle Peter, “Thy dog…hath run twice to Rome, and he would run the third time if thou gavest him leave.” “Then the devils let him loose,” says the saga, “and Hrafn got across the river.”

Samuel Watson, The Battle 0f Cl0ntarf, 1844 But fellow Orkneyman Thorstein halted at the water’s edge and, seeing the Gaels coming at him, merely knelt to tie his shoelace. At the sight the Gaels stopped to ask why; Thorstein answered. “Because I can’t get home tonight, since I am from Iceland.” The Irish gave him quarter. “The foreigners are defeated,” Latean reported to Brian, “and Murchadh’s standard has fallen.” “That is sad news,” quoth the king, “on my word, the honor and valor of Erin fell when that standard fell.” Latean advised Brian to mount his horse and ride to where the surviving Irish could rally round him: “We know not who may approach us where we are now.” “O, thou boy,” Brian told him, “retreat becomes us not, and I myself know that I shall not leave this place alive.” He began giving instructions to be carried out after his death. Latean interrupted. “There are people coming towards us here…a blue stark people.” “The foreigners of the armor,” said Brian, taking up his sword. It was Brodir, who had skulked in Tomar’s Wood for much of the battle. “Brodir saw that King Brian’s men were chasing the fleers,” goes the Icelandic saga, “and that there were few men by the [king’s] shieldburg. Then he rushed out of the wood, and broke through the shieldburg, and hewed at the king.” According to the chronicles, even as Brodir raised his axe, Brian cut his legs from under him, but “the foreigner dealt Brian a stroke that cleft his head utterly.” Brodir called out, “Now let man tell man that Brodir felled Brian.” Norse writers claim Ulf the Quarrelsome took Brodir alive, opened his belly, nailed his entrails to a tree and marched him around it, “and he did not die before they were all drawn out of him.” The Irish had taken the field, but had not the strength to take the city. The Vikings gave up any attempt to conquer Ireland. The only winners of Clontarf were those who refused to fight: Malachy reclaimed the High Kingship; Sigtrygg Silkbeard stayed on the throne of Dublin until his death; and Gormflaith saw her son Donnchadh crowned King of Munster. In the thousand years since, Clontarf has risen to an almost mythological importance in Irish history, when the fractious clans united to repel the invader. As a Viking saga put it, “Brian fell, but kept his kingdom, ere he lost one drop of blood.”

M0re fr0m D0n H0llway:

|