In December 1969 the rescue of two downed US airmen

snowballed into one of the biggest battles of the Vietnam War

|

by Don Hollway

F-4C-17-MC Phantom 63-7444, 558th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 12th Tactical Fighter Wing

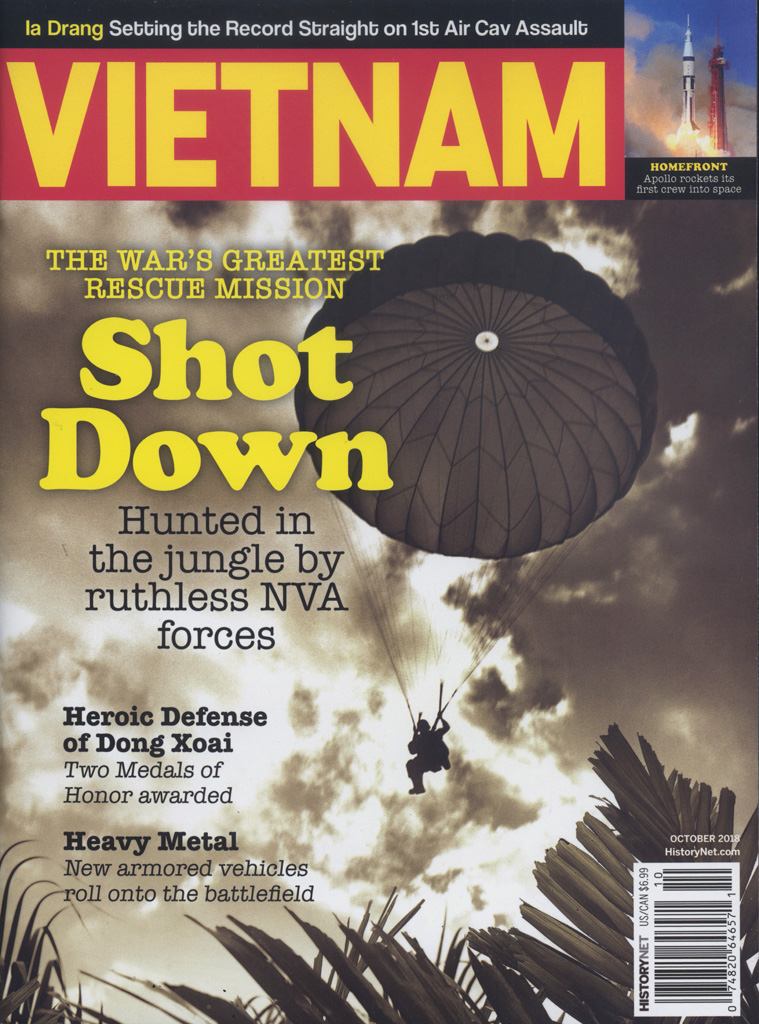

The mission went wrong almost from the start. Two U.S. Air Force F-4C Phantoms of the 558th Tactical Fighter Squadron, call sign “Boxer,” found their primary target weathered over. They diverted north to the village of Ban Phanop, Laos, near a choke-point where the Ho Chi Minh Trail crossed the Nam Ngo River, to sow the ford with Mk-36 mines—500-pound Mk-82 low-drag bombs with pressure fuzes in their tails. “There’s [anti-aircraft] guns all over around here,” advised “Nail 12,” the local FAC (Forward Air Controller), from his OV-10 Bronco, “but I haven’t seen them shoot today.”

Ho Chi Minh trail crosses the Nam Ngo River

It was Friday morning, Dec. 5, 1969, and Boxer 22 was about to become the objective of the biggest rescue mission of the Vietnam War. Read the incredible story of the fight to save Boxer 22 in the October 2018 issue of VIETNAM magazine.

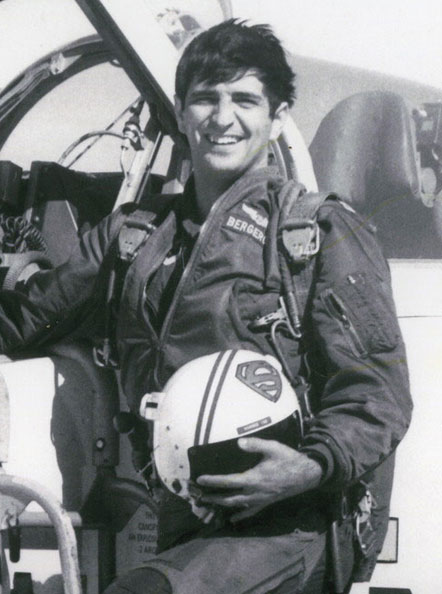

F-4C-17-MC Phantom 63-7444 On ejection, remembered Bergeron, “The windblast knocked my helmet off and got my nose. The chutes were fairly close. As I was coming down, there was a guy shooting at me with a 12.7 [mm machine gun].” He landed in a bamboo thicket at the bottom of a 20-foot embankment. “When I got on the ground, the shots were ricocheting over my head on top of the ground. I happened to land right at the edge of the river in a little cleared area about ten by ten. I hit the ground running. My chute was stuck in a ten-foot high bush. Ben’s (across the river) was in about a forty-foot tree.” They had come down only about a hundred feet apart, but on opposite sides of a dogleg in the Nam Ngo. (Their F-4 impacted half a mile away, just two yards from the target.) Danielson broke an ankle in the tree. Both immediately activated their radio survival beacons. Overhead, the FAC radioed King 1, one of the HC-130 Hercules airborne command posts orbiting 24,000 feet above Laos 24 hours a day. “Mayday, mayday, mayday, this is Nail 12. Boxer 22 has punched out. We have two good ’chutes and beepers.”

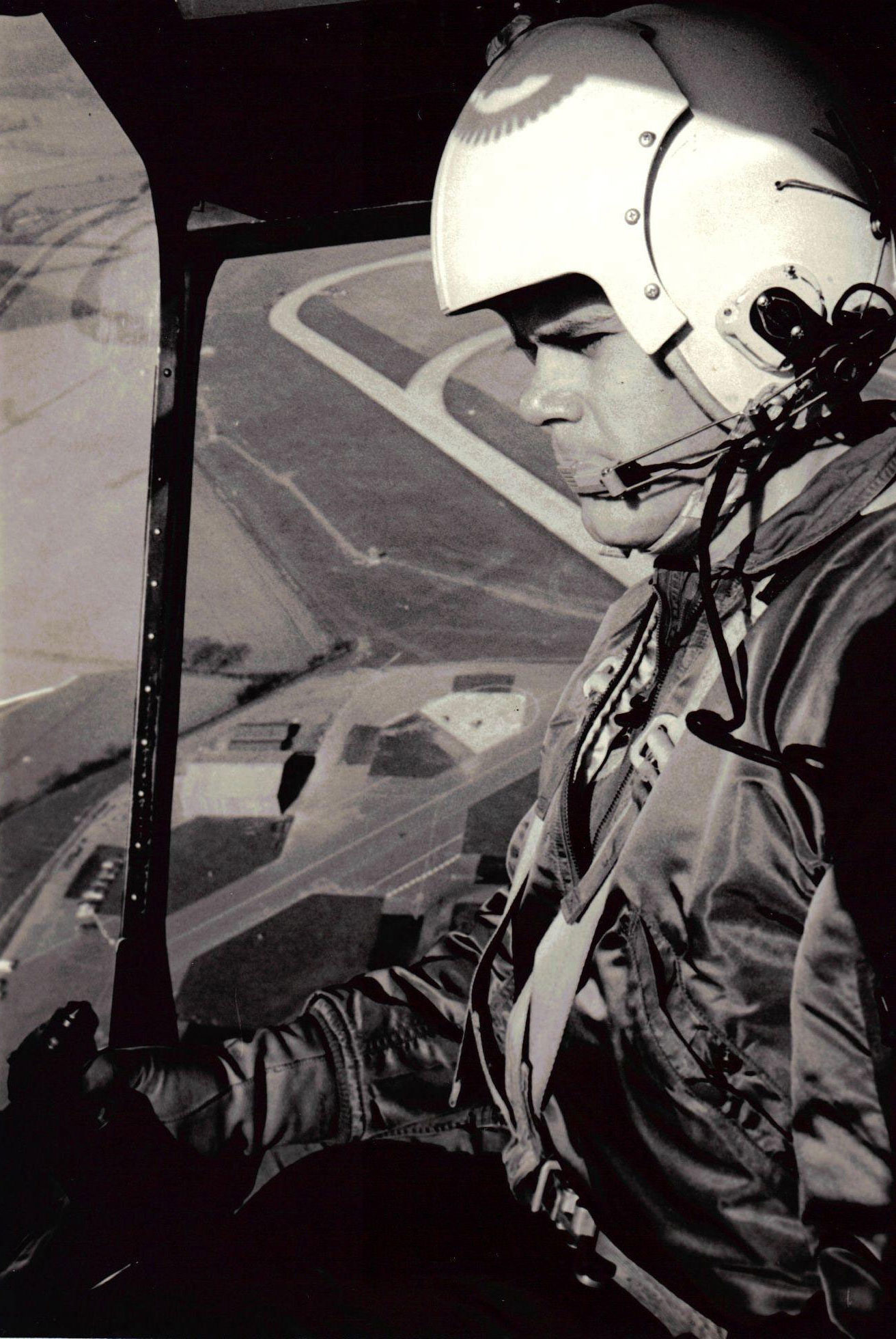

Ho Chi Minh trail, Phanop Valley choke point US Air Force footage: Danielson and Bergeron—Boxer 22 Alpha and Bravo—had landed in a valley a mile across and a thousand feet deep, walled with karst, limestone cliffs. They were just ten miles from the North Vietnam border, but only about 65 miles east of NKP—Nakhon Phanom Royal Thai Airbase, main base of the Air Force Special Operations Squadrons, specializing in SAR (Search and Rescue). Their A-1 Skyraider fighter-bombers scrambled, and the summons went out to Jolly Green Giant rescue choppers, forward air controllers and fast jets. The trick was to pull the downed airmen out as quickly as possible, a “fast SAR,” before enemy forces concentrated on the area and turned it into a “shoot ’em up SAR.” The problem was, at Ban Phanop the enemy was already concentrated.

1st Lt (later Lt. Col.) James G. George Leading a four-flight of A-1 Skyraiders, 1st Lt. James G. George arrived over the valley at 1108 hours and, as per standard operating procedure, took charge of the rescue as “Sandy 1.” He immediately made radio contact with Danielson and Bergeron (now “Boxer Two-Two Alpha” and “Two-Two Bravo”) and the Spads began suppressing local ground fire. Meanwhile F-100 Super Sabres and F-105 Thunderchiefs took on the heavy gun emplacements surrounding the valley. Worst was a 37mm gun in a cave at the foot of the karst 300 meters right behind Bergeron. The only way to kill a gun in a cave was to drop a bomb directly inside—given the terrain, almost impossible. In the end they resorted to spraying the cave mouth with 20mm shells.

A Douglas A-1E Skyraider drops napalm and “Willie Pete” (white phosphorous) on an enemy position.

A-1H Skyraider 52-139738, originally U.S. Navy AD-6 Bu. No. 139738, authorized in 1952. 1st Special Operations Squadron, Nakhon Phanom RTAFB, Thailand, 1972. “Proud American” was flown by Lt. Col. William Jones of the 602nd SOS when he won the Medal of Honor on Sept. 1, 1968. Severely damaged, it was repaired, but on Sept. 28, 1972, it became the last Skyraider lost in the war, over northern Laos. Pilot 1Lt Lance Smith was rescued. USAF footage: It didn’t take long for the Americans over Ban Phanop to realize the enemy below was heavier than expected. The call went out for more help. Da Nang sent six A-1s packing tear gas cluster bombs. NKP sent two large Jolly Green helicopters. Ubon RTAFB sent four F-4 Phantoms with Paveway laser-guided bombs to pinpoint the 37-mm gun. Many of these Americans, however, had no idea what they were getting into. Aircrews’ term of service in Vietnam was one year or 100 missions, but the previous such large-scale rescue attempt had been almost a year earlier, in March 1969, before most of these pilots ever arrived in-theater. The North Vietnamese, however, had been using the Trail since 1959, had spent years carving gun positions into the limestone cliffs around Ban Phanop, and would fight until victory or death.

Capt. Charles W. Hoilman By 1240 hours the chance of a rescue was as good as it would get. Capt. Charles Hoilman, piloting JG-37, was briefed to pick up Danielson first, whose position was marked by his tree-bound chute, and if possible sidle across the river to get Bergeron. “During a rapid descent into the valley from the southwest, my flight engineer and PJ notified me that we had an ever increasing trail of flak following us down to the pickup point. During the descent I observed an F-105 deliver a Paveway bomb into the mouth of a cave from which the 37-mm gun was firing; the gun was pulled behind a steel door before the Paveway bomb exploded and, incredibly, the gun was back out and firing at the F-105 as it passed by the target. A few seconds later, as I flared to a hover over the pilot, all hell broke lose, small arms and 12.7-mm ground fire came from all directions and my Jolly Green was taking hits on all sides, so I immediately evacuated the area. As fate would have it, none of my crew members were hit and we were able to limp back, unescorted, to NKP for repairs.”

Col. (later Major General) Daryle E. Tripp At 1645 hours Col. Daryle Tripp, deputy commander of the 56th Special Ops Wing out of NKP, took charge as On-Scene Commander in Skyraider Sandy 7. “By this time in the war, the North Vietnamese responsible for the defense of the Ho Chi Minh Trail had seen enough of us to know how to counter our tactics,” he knew. “Theirs was simply a hold fire and wait for the Jollys, the ultimate flypaper that would surely attract more flies.” “All the Sandys would come around and troll [for enemy fire] and nothing happened,” Bergeron realized, “and as soon as the Jolly Greens came in every gun in the world opened up....So then they pulled them out and tried to knock out all the guns and kept trying to come back and the guns kept getting them and the choppers took some unbelievable hits.”

The HH-3 had been flying combat SAR duty since July 1965 but was an improvised solution to the problem—underpowered and, with just one M60 machinegun that could be used while the rescue hoist was in action, lightly armed. At NKP the HH-3 was nicknamed Nitnoi, Thai for “little one.”

In 1969 the new HH-53 “Super Jolly Green,” was just coming into service, with improved armor, more powerful engines (it could hover on just one) and three multi-barreled, electrically powered 7.62 Gatling miniguns Maj. Jerry Crupper brought in his HH-53, JG 79. He reported, “Tracers were passing all around us and we were hit in the belly of the Jolly, on the cargo hook, with a 37mm air burst.” The explosion blew parajumper A1C Terry Caffery off his feet. “The helicopter began to go inverted and I decided I had better bail out,” he said. “…The next thing I remember was waking up from becoming temporarily unconscious.” Despite a 2x4-foot hole in its bottom and a cut fuel line spraying flammable JP-4 jet fuel around inside, the Jolly crew stuck with their ship and made it back to NKP. “It's a good thing did not bail out,” Caffery remembered. “Back at base the riggers discovered my parachute was riddled with shrapnel and three AK-47 rounds. Maintenance counted over 200 bullet holes in the chopper, including three rounds that went through the tail rotor shaft.” Major Hubert Berthold’s Jolly 68 was next in: “Boxer 22 Alpha was spotted 25 meters north of his parachute. He was standing near a small clump of trees and waving the night end of his flare. As I slowed to a hover and was approximately 150 feet from the survivor, the entire area lit up with tracers from both sides, from both the karst and the ground....I started a go around and jinked away from the streams of tracers....Ground fire was received continuously until we were five miles west of the survivor.” Daylight was running out, and in those days the Air Force had no night SAR ability. Tripp told everyone, “We have at least 45 minutes to sunset. We will make at least one other attempt. But it’s fairly apparent from the gunfire out here that I just saw that there is still more work to be done.” With only twenty minutes of daylight left, Capt. Donald Carty, flying JG-72, radioed Tripp: “Sandy 7. This is Jolly 72. Come on Sandy. Let’s do it with what we’ve got.” Tripp and his wingman tried to silence the cave guns with cannon and 2.75-inch rockets. Even Tripp’s Skyraider took a hit. “A tactical approach enabled us to get within 30 feet of Boxer 22 Alpha,” remembered Carty, who ran into the same sheets of tracer fire as every Jolly Green before him. “...The enemy troops were well entrenched and had caught us in a cross fire of ZPU, 23mm and 27mm antiaircraft fire....We were so low and it was so dark on the egress that we almost hit the karst....I advised against making another attempt because it was too dark and our miniguns were either jammed or out of ammo.” 90 combat aircraft had taken part in the operation over Ban Bhanop. They had dropped almost 350 munitions. Seven helicopters had taken serious hits; five of them were unlikely to be ready in the morning, and two might never fly again. Airman Davison had given his life, and there was nothing to show for it. At 1745, with the valley in darkness, all that could be seen was the streams of tracer fire reaching relentlessly up for the aircraft. One Spad pilot recalled, “The AAA was firing above us across the entire valley with the tracers ricocheting off the side of the karst on the opposite side. It was like being in the bottom of a tunnel of fire.” Tripp broke the news to the Boxer 22 crew: “We have run out of helicopters and I want you to bed down. Try to get yourself dug in and we will be out here first thing in the morning.”

Read the incredible story of the fight to save Boxer 22 in the October 2018 issue of VIETNAM magazine. USAF footage: Woodie Bergeron tells the story of Boxer 22

SAVING BOXER 22 By Don Hollway Lest We Forget Davison wears the red beret symbolizing sacrifice, which was the the pararescueman’s mark of distinction since early 1966. Capt. Holly G. Bell flew the first HH-53 Super Jolly Green Giant to the Boxer 22 crash site, in the course of which A1C Davison was killed. Two months later Bell and his entire crew were killed in action during another SAR mission, when their Super Jolly was hit by an air-to-air missile fired from a MiG-21 flown by North Vietnamese ace Vu Ngoc Dinh of the NVAF 921st Flight Regiment. Flight Engineer Sgt. William Shinn, who had hoisted Bergeron aboard Jolly Green 77, was flight engineer aboard Bell's HH-53 when it was shot down, all board KIA. Closure

Navy Cmdr. Brian Danielson, left, greets retired AF Lt. Col. Jim George, veteran of the Boxer 22 rescue, on completing Heritage Flights in Randolph Air Force Base’s T-38 jets in honor of Air Force Maj. Ben Danielson and all the airmen who fought to save Boxer 22. Read the incredible story of the fight to save Boxer 22 in the October 2018 issue of VIETNAM magazine. More from Don Hollway: Comments loading....

|