|

Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, circa 1970 A month before the fall of Nazi Germany, Maj. Robin Olds of the 479th Fighter Group, U.S. Army Air Forces, scored his final aerial victory of World War II, chasing a Messerschmitt 109 through a formation of Consolidated B-24 bombers to shoot it down. More than two decades later, on Sept. 30, 1966, a U.S. Air Force Lockheed C-130 dropped Olds, colonel by then, and the rest of the passengers on the wrong end of a runway at Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, home of the 8th Tactical Fighter Wing. “We stood on a piece of hot concrete a mile away from base ops, the sun beating on us from a brassy sky,” Olds would write in his memoir of going to war second time. “A fine greeting for their new commander.” The pilots of the 8th TFW, the “Wolfpack,” had bigger worries than catering to a new commanding officer. In January 1966 the North Vietnamese air force fielded new Soviet-built Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 “Fishbed” interceptors. Using heat-seeking missiles in ground-controlled hit-and-run tail attacks, they were exacting a toll on the US Air Force's Republic F-105D Thunderchief bombers In six months from April to September the Wolfpack had lost 18 F-4 Phantom II fighter-bombers in six months—eight that September alone. 1st Lt. Ralph Wetterhahn of the 555th Tactical Fighter Squadron, the “Triple Nickel,” remembered, “Twenty-two pilots were dead or missing.” The Cold War Air Force was all about intercontinental ballistic missiles and strategic bombers. Fighter planes, fighter pilots and fighter combat were considered “old hat.” Double-ace Olds, with his foul mouth, hard drinking and movie-star wife, Ella Raines, rubbed the bomber generals the wrong way. One told him, “You’re not going to put on your leather jacket, your scarf, your helmet and goggles and go out and do battle with the Red Baron. You’ve got to get it into your head: we’re never again going to fight a conventional war.” Olds had missed the fighting in Korea, but finally ticked off somebody enough to get himself sent to Vietnam. “It had been twenty-two years since I’d fought in a war,” he later recalled, “but it was obvious where my task lay.” The young fighter jocks at Ubon were equally leery of the “Old Man,” who at 44 was twice their age and hadn’t so much as flown a Phantom or fired a guided missile until a few weeks earlier. “We had heard about Olds,” Wetterhahn said. “He had flown P-51 Mustangs and P-38 Lightnings over Europe in World War II and had scored 12 kills in dogfights. We’d also heard that he had been on the general’s list some years ago, but had been redlined from promotion. We were curious to meet this resurrected bad boy, and soon after his arrival everybody got the opportunity. He ordered all pilots to come to the main briefing room—the first time we’d all been brought together.” Capt. John B. Stone of the 433rd Tactical Fighter Squadron, “Satan’s Angels,” never forgot Olds’ intro: “I’m the new guy. You know a lot that I don’t know, and I’m here to learn from you. But in two or three weeks, I’m gonna be better than all of you. And when I know more about your job than you do, you’re in trouble.”

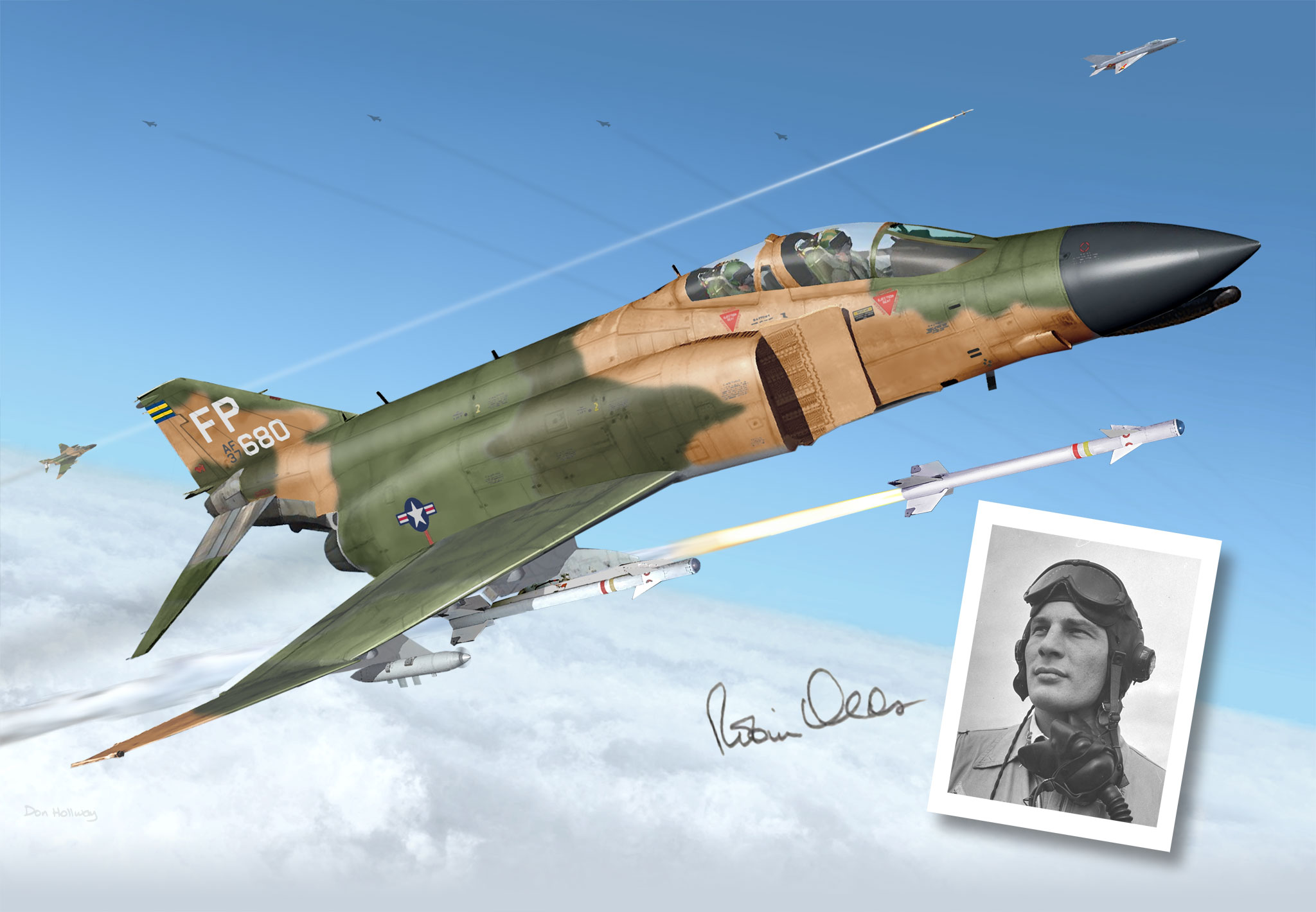

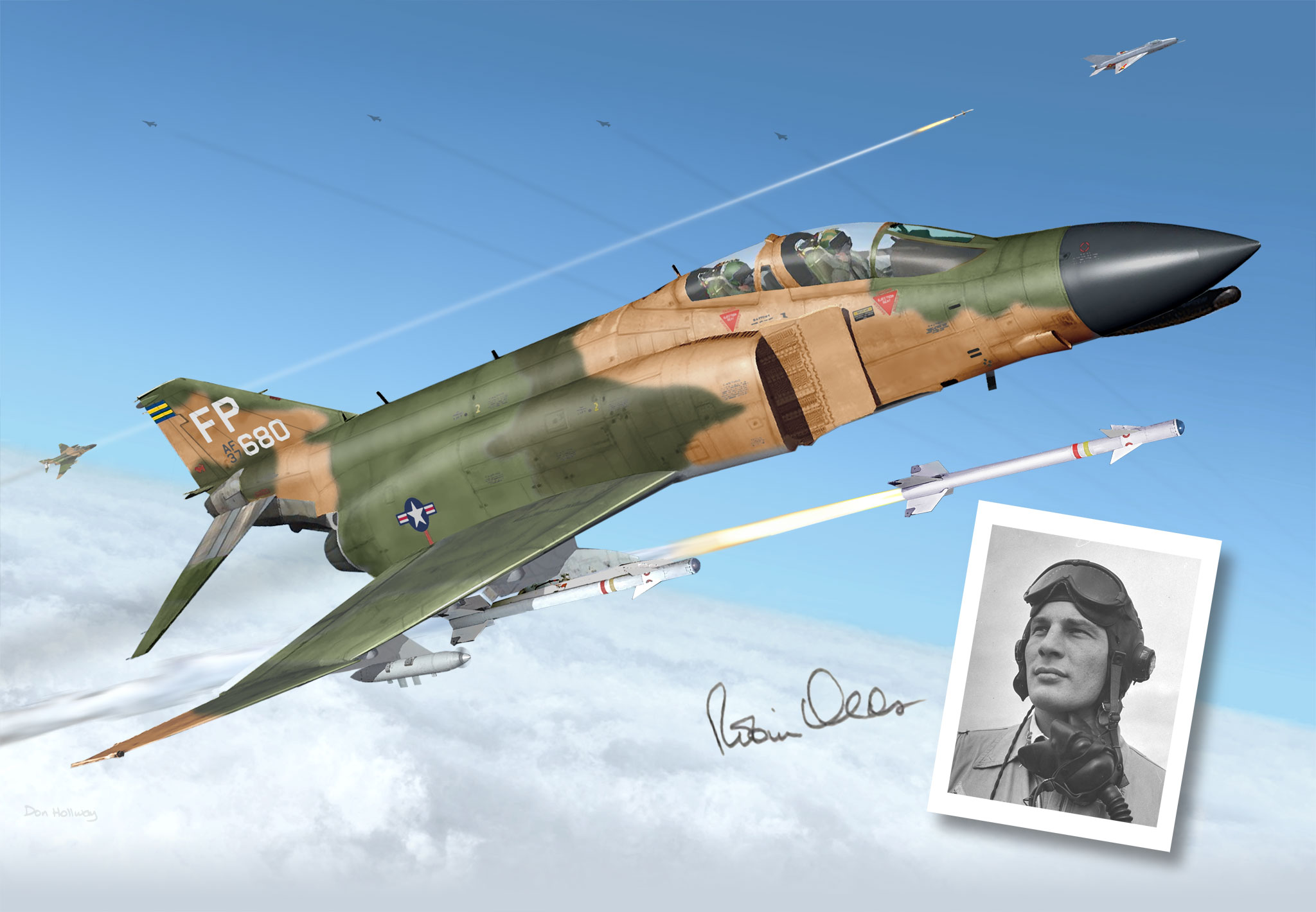

F-4C-24-MC Phantom II #63-7680

“It looks as if somebody had got it halfway out of the hangar and shut the door on it.” That’s how one Air Force pilot described the McDonnell Douglas F-4 Phantom II, adding, “It’s bent in the middle, its wings go up, its tail goes down—but it flies wonderfully.” With nicknames like Rhino, Double Ugly, Old Smokey, the Flying Anvil and Lead Sled, the Phantom didn’t earn its reputation on looks. Created as a Navy jet to take off from carriers and defend the fleet from enemy attack planes, it was forced on the Air Force by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. However, when the Air Force brass learned that the F-4 could hit Mach 2.5, reach 98,000 feet and carry a heavier bomb load than a B-29 Superfortress (if not all at the same time), they were happy to take it.

Stone, a veteran of more than 50 missions up north, had an idea. Because the MiGs were avoiding the F-4 Phantom fighters and focusing their attacks on the F-105 Thunderchief bombers, the F-4s should disguise themselves as F-105s to lure the North Vietnamese aircraft into a dogfight where the Americans could destroy them, Stone reasoned. That October the F-105s, nicknamed “Thuds,” had been equipped with new electronic equipment that jammed radar and blocked tracking systems the North Vietnamese used in guiding their SAMs. Olds and Stone decided to borrow some F-105 jammers and rig them to the Phantoms, making them appear to enemy radar as Thuds. “Our ruse was simple,” Olds wrote. “Our F-4s would mount a typical large strike using the F-105 call signs, routes, and timings, the routine stuff that the North Vietnamese were used to seeing in the predictable bombing raids by the Thuds; but we would be armed for air-to-air combat.” The F-4 carried four radar-guided AIM-7E Sparrow missiles and four heat-seeking AIM- 9B missiles. If the MiGs fell for the bait-and-switch, they would encounter not Thunderchief bombers but instead waves of Phantoms, all loaded and ready for a fight.

F-4C-19-MC s/n 63-7589 FP flown by 1/Lt Ralph F. Wetterhahn and 1/Lt Jerry K. Sharp, 555th TFS, 8th TFW, Ubon, Thailand, 2 January, 1967

Olds spotted a MiG at 10 o’clock, crossing right to left. He went after it with full-burner: “I got on top of him and half upside down, hung there, and waited for him to complete more of his turn.” Olds had never been to Fighter Weapons School. He’d learned to kill MiGs by killing Messerschmitts, maneuvering with pure fighter-pilot instinct. “I’m not sure he ever saw me. When I got down low and behind, and he was outlined by the sun against a brilliant blue sky, I let him have two Sidewinders, one of which hit and blew his right wing off.”

More from Don Hollway: Comment Box is loading comments...

|