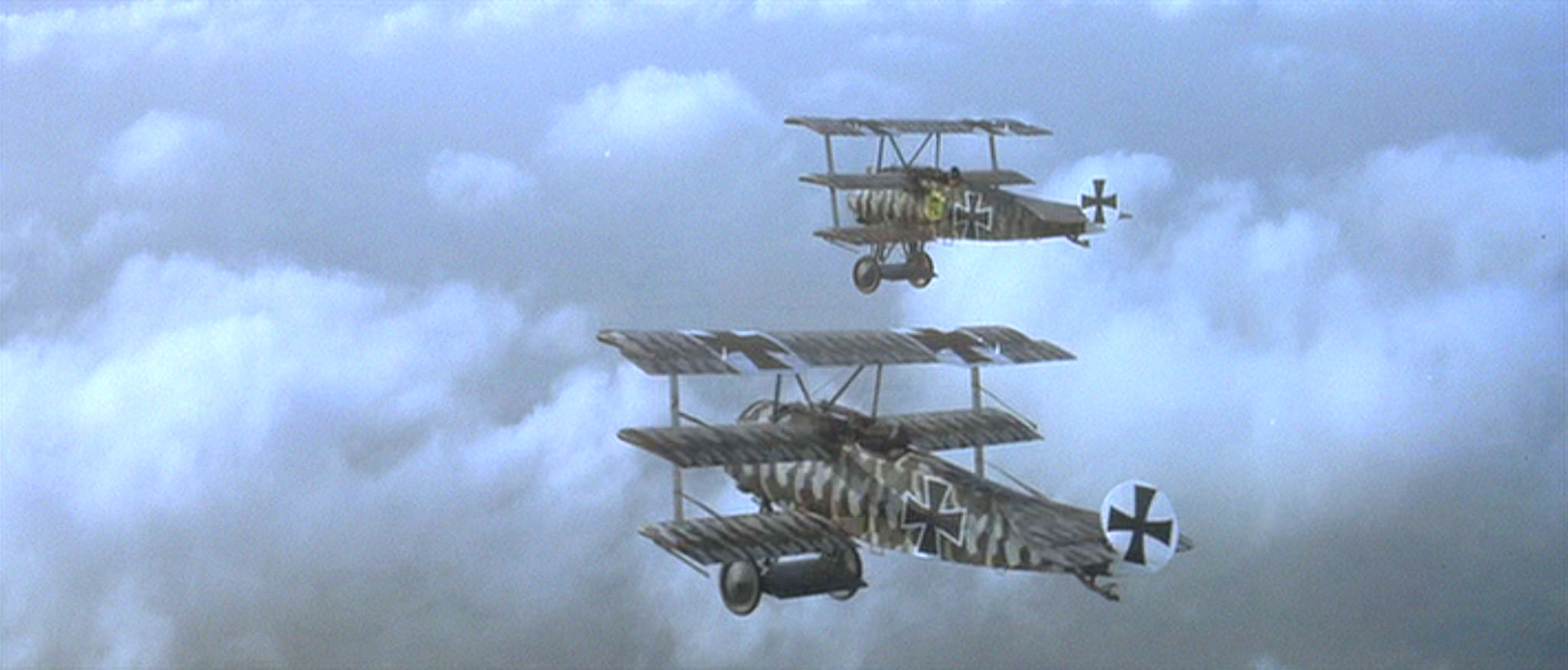

Filmed 50 years ago, long before the advent of CGI,

the World War I aviation epic required two air forces built from scratch

and stunt pilots willing to risk everything flying them

Filmed 50 years ago, long before the advent of CGI,

the World War I aviation epic required two air forces built from scratch

and stunt pilots willing to risk everything flying them

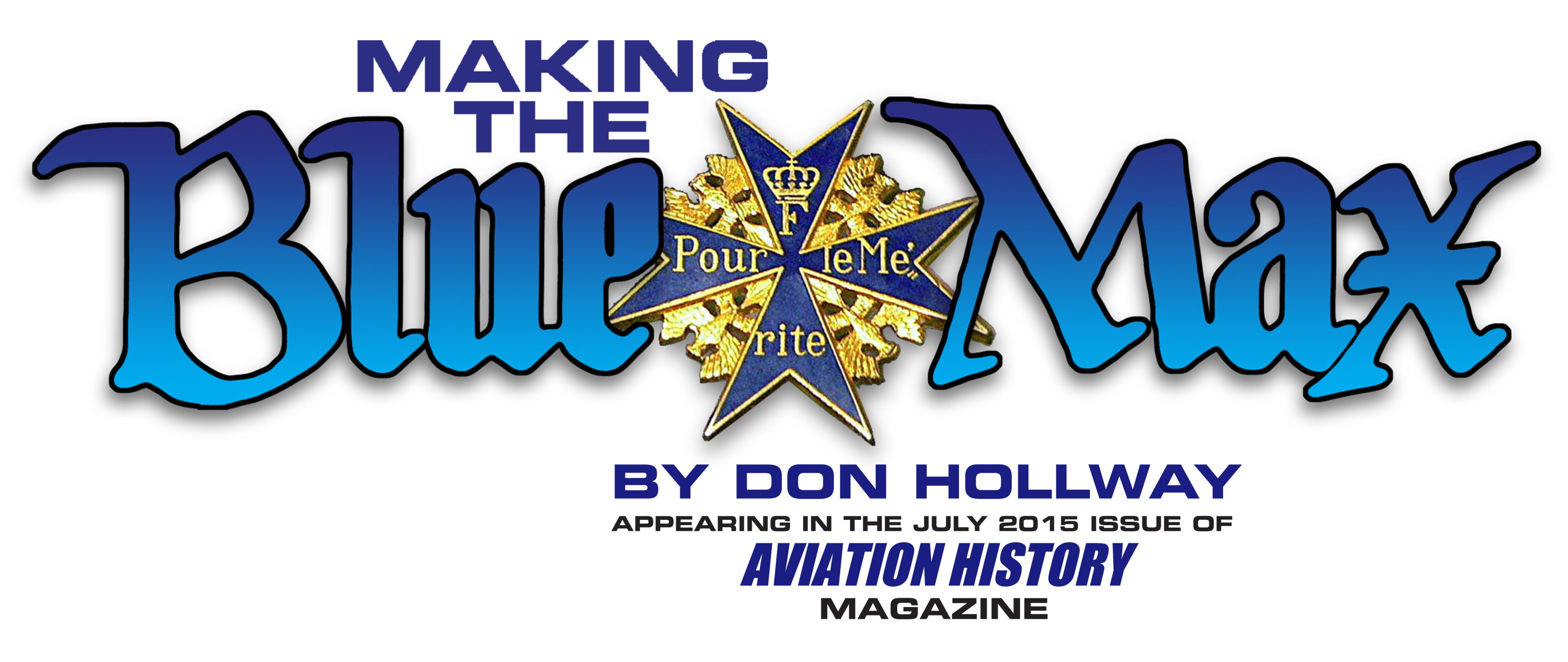

Derek Piggott in the cockpit of a Slingsby T53 glider in 1952, with Fred Slingsby (left) & designer J.L. Sellars. Slingsby actually served in the Royal Flying Corps in WWI as a gunner/observer. Once, when his pilot was killed, Slingsby climbed from his cockpit and into the pilot’s, took control of the aircraft and flew back to British lines.Arriving at Ardmore Studios, Dublin, Ireland, in 1965 to begin work on a new 20th Century Fox World War I dogfight movie, stunt pilot Derek Piggott learned he was in for more than just zooming around the skies, popping off smoke bombs and fake bullets while cameras rolled. The script called for a biplane to fly under a bridge, and producer Christian Ferry did not intend to use remote-control models. He meant to make the greatest WWI air combat film of all time: The Blue Max. “He must have had photos of almost every bridge in Ireland,” recalled Piggott, who had flown Airspeed Horsa gliders for the RAF in World War II, set a postwar glider altitude record (22,800 feet without oxygen) and broken into movies flying pre-WWI replicas in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines. “I often wonder now whether Christian showed all the pilots these photos in order to see their reaction, and to try to decide who he would ask to do the job when the time came. Perhaps I was the only pilot who did not say that all the bridges looked quite hopeless.” Not to mention that the stunt would have to be flown in an airplane virtually hand-built from scratch. Aircraft made of wood and cloth tend to rot, and five decades after the Great War the owners of the few surviving WWI warbirds weren’t inclined to risk them making movies. The Blue Max required Fox to assemble two miniature air forces, at the cost of about a quarter of a million dollars—in today's money, nearly $2 million.

In 1927 it wasn’t as difficult to come up with WWI warbirds as it would be nearly 40 years later The Blue Max was really almost 40 years in the making. 1927 was a banner year for aviation. In May, Charles Lindbergh made the first solo flight across the Atlantic. In September a Supermarine S.5 seaplane won the Schneider Trophy with a record speed of 453mph. And on a snowy winter night in Buffalo, NY, six-year-old Jack D. Hunter was taken by his mother, who couldn’t find a babysitter, to see Clara Bow and Gary Cooper in Paramount Pictures’ WWI aviation epic, Wings. “I sat motionless and starry-eyed through the dogfights and balloon-busting and plane crashes,” he would recall 70 years later of the black-and-white silent. (Hunter was red-green colorblind.) “I came away from the theater totaled by my first love affair, afire with a passion for flying machines.”

The late Jack D. Hunter with a portrait of himself as a young airman in 1939. Learning German partly through his own efforts to translate Der Rote Kampflieger (The Red Battle Flier, the memoirs of Manfred von Richthofen), instead of becoming an Army Air Corps pilot, Hunter did intelligence work, going into occupied Europe at war’s end. Helping to infiltrate, expose and take down the budding Nazi resistance movement obliterated any admiration he had left for war heroes. “Bölcke and Voss and Bishop and McCudden and Ball and Guynemer and Luke had lost the idealistic, operetta-like glitter my boyhood had given them,” he wrote, “and had become in my mind what I’d seen around me as an adult: miserable, lonely, homesick men who killed to keep from being killed.” One particular imprisoned SS Obersturmbannfuehrer simultaneously repelled and intrigued him: “Handsome, erudite, suave, amiable, and witty [but] also a thoroughgoing rat, a ruthless psychopath who’d kill at the drop of an umlaut, and you never knew when which side of him would turn up…. What happened in his early life that enabled this seemingly pleasant, balanced man to get so much fun out of war and its concomitant evils? “There’s a novel in that,” Hunter thought. “And someday I'm going to write it.” Returning home to build the American Dream came first. Not until 1962, when he was a 41-year-old journalist and speechwriter, did Hunter sit down to tell the story brewing in him all those years, which—writing longhand late into the night—he knocked out in seven months. No less than nine publishers refused to touch a novel about “a gaggle of nudnik Germans in a war nobody remembers,” but E.P. Dutton rolled the dice and inadvertently tapped into a rising tide of nostalgia for WWI aviation. Cole Palen’s Old Rhinebeck Aerodrome show was just getting off the ground in upstate New York; the “Cross and Cockade” historical aviation society had taken off in 1960. When The Blue Max hit bookstores in March of ’64, the New York Times gave it an extensive review, Bantam bought the paperback rights, and in less than two weeks Darryl Zanuck of 20th Century Fox optioned the movie. The producers were only too aware, however, that aviation buffs alone wouldn’t suffice for an audience. They would need big names to bring in the numbers.

“Bruno Stachel” gets a haircut from hairdresser Jay Sebring, later murdered with actress Sharon Tate and two others by members of the Manson Family. “With the assignment of George Peppard, the winsome and totally apple-pie-American superstar, to the lead role,” recalled Hunter, “I saw that the Bruno Stachel of the novel would never make it into the movie.” At 37, Peppard was nearly twice the age of Hunter’s Stachel, or for that matter any actual German pilot of the war. To compensate, Swiss beauty Ursula Andress signed as Stachel’s love interest and nemesis, the Countess Kaeti von Klugermann. Stereotyped as a bikinied sex kitten in Dr. No, Fun in Acapulco and What’s New Pussycat?, she would add vengeful bitch to her repertoire, though her voice, as in Dr. No, and most of her other movies, was dubbed to disguise her thick Swiss-German accent. (No one was interested in her voice.) Britishers James Mason and Jeremy Kemp and Germans Karl-Michael Vogler and Anton Diffring ably filled out the cast. Cast

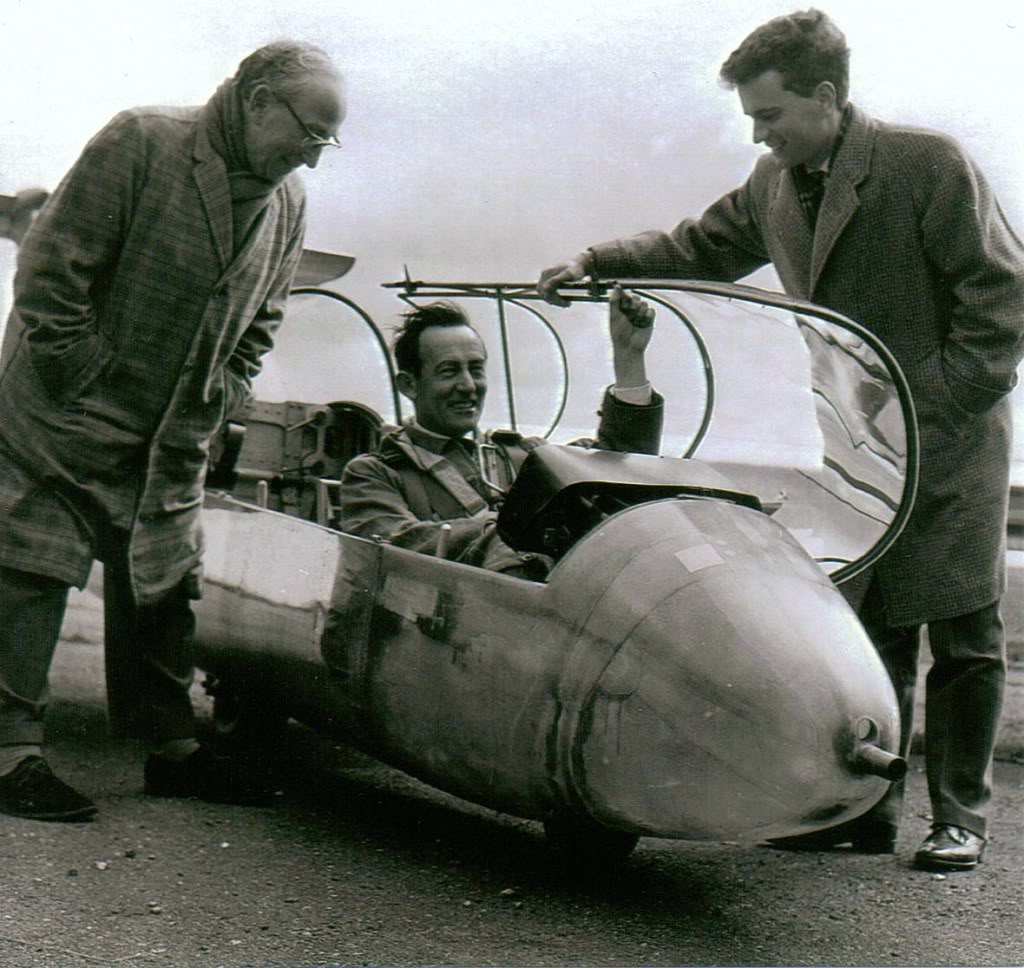

“It’s cruel world, Herr Hauptmann. You said so yourself.” George Peppard as Bruno Stachel. In 1965 Peppard was near the peak of his career, coming off Breakfast at Tiffany’s, How the West was Won, and The Carpetbaggers, where he met Elizabeth Ashley, his fiancée during filming of The Blue Max. (They divorced in 1972.) He had recently finished the WWII commando movie, Operation Crossbow, which also featured Jeremy Kemp. Peppard was infamously difficult to work with, for which his career suffered. He died in 1994 of lung cancer.

“Tonight is a family affair. Are you shocked?” Ursula Andress as Kaeti von Klugermann. Already famous as the first Bond girl, in the summer she made The Blue Max, Andress posed nude for Playboy, “Because I’m beautiful.” The year the movie came out, she divorced her husband of nine years, John Derek, who had photographed the magazine shoot and masterminded her career. He would do the same for future wives (and Andress lookalikes) Linda Evans and Bo Derek. The Blue Max demonstrates that, though never underrated for her beauty, Andress was underrated as an actress.

“Stachel...there is something of the cobra in you. I’ll have to watch you.” Jeremy Kemp as Stachel’s rival in love and war—and yet closest friend—Willi von Klugermann. The role put Kemp on the map, and he would soon play “Col. Kurt von Ruger” in 1970’s Darling Lili, which also starred many of the planes flown in The Blue Max. Kemp has gone on to have a long, successful career, but nobody who’s seen The Blue Max can think of him as anyone but Willi von Klugermann.

“Herr General, I see now I have notions of honor which are outdated.” Karl-Michael Vogler as Otto Heidemann. Vogler made his first English-language appearance in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines (on which Derek Piggott also got his start as a stunt pilot). In 1970 he appeared as Erwin Rommel, opposite George C. Scott in Patton. After that he worked primarily in Germany. He passed away in 2009.

“If I court martial him now it will reflect on the integrity of the whole German officer corps.” James Mason as Gen. von Klugermann. By the time he appeared in The Blue Max Mason had been acting for 30 years, and achieving top bill for 20. He had recently starred in Lolita and would immediately go on to appear in Georgy Girl, for which he won an Oscar as Best Supporting Actor. His career was still going strong in 1984, when he died of a heart attack.

Stachel: “What are you going to put under the picture? Squadron commander’s wife nurses wounded hero?” Anton Diffring as Holbach. Diffring was born in Germany in 1916, when WWI was still underway, and during WWII was interned in Canada as a subversive. He made a career of playing Germans in war movies, including Where Eagles Dare, Colditz Story, and Zeppelin, in which some of the Blue Max aircraft also appeared. He died in 1989.

more...Star George Peppard took the role of Stachel so seriously that he actually learned to fly. “Before production on The Blue Max, I took an intensive four-month flying course, which gave me 210 hours on my pilot’s log, 130 of them solo,” he reported. “I then checked in at our location in Ireland and spent an additional month flying the re-creations of early aircraft built for the film.” He proved it on the cover of the May 1965 issue of Air Classics magazine, flying a Stampe in German colors. Anthony Squire, a WWII flying boat pilot who learned movie work with the RAF Film Unit, would direct the air action. German WWI pilot Kurt Delang, with two victories as a senior NCO in Jasta 10, served as technical adviser. Director John Guillermin, thus far best known for Tarzan movies, was determined to make the most of his big break. “Life isn’t really filled with many heroes,” he said of the story, or perhaps the pilots he asked to fly his planes, “but there are men like [main character] Bruno Stachel who strive to achieve greatness against such overwhelming odds that the attempt, to lesser men, must seem not only impossible but madness.” The crew

Stunt Pilot Derek Piggott gives flying instruction to star George Peppard on the set of The Blue Max. Peppard learned to fly for the role, and proved it on the cover of Air Classics magazine. Co-star Andress appears to have at least gone up for a ride.

Stunt Pilot Charles Boddington, who flies the triplane barrel roll just before The Blue Max bridge scene. See also this view. In Sept. 1970 he was killed flying an SE.5 replica during the filming of Von Richthofen and Brown.

Stunt Pilot Lynn Garrison, who later bought the entire “Blue Max” fleet, and was instrumental in keeping the red triplane alive. He made his money flying as a mercenary in Africa and Latin America.

Stunt flier Lynn Garrison, a colorful ex-Royal Canadian Air Force pilot, airshow promoter and aircraft collector, helped assemble the fleet. In German and British paint schemes, a Caudron C.276 Luciole served as a reconnaissance plane for both sides. De Havilland D.H.82 Tiger Moths and a pair of Stampe SV.4Cs with their front cockpits faired over filled out dogfight sequences. A similarly converted French Morane-Saulnier MS.230 stood in for the Fokker E.V parasol monoplane in the film’s final sequence. Meanwhile Bitz Flugzeugbau GmbH of Augsburg, West Germany, built two Fokker Dr.I triplanes, and Rousseau Aviation of Dinard, France, constructed three Fokker D.VII biplanes. Personal Plane Services, in Buckinghamshire, England, built a Pfalz D.III, and the Hampshire Aero Club another. For the “enemy,” Miles Marine and Structural Plastics Ltd. of Shoreham, England, built two S.E.5a scouts.  A Bitz triplane and three Rousseau “D.VII-65s” warming up for takeoff in a “Blue Max” production scene. See also this view.

Given time and material constraints, some sacrifices to authenticity had to be made. The PPS Pfalz was a rebuilt de Havilland Gipsy Moth with a 4-cylinder 140-hp Gipsy Major engine, including a pair of fake cylinders and exhausts to enable it to pass for the original Pfalz’s 160-hp Mercedes inline-6. Similarly, the Bitz triplanes used Siemens-Halske SH-14 radials instead of Oberursel rotaries. Gipsy Queen 3 200-hp 6-cylinder inlines powered both the S.E.5as and D.VIIs; since the Fokkers’ original Mercedes weighed almost twice as much, they required some 200 pounds of nose-ballast for balance. Rousseau named its models the D.VII-65. “Most of the aircraft for The Blue Max were constructed in less than five months,” Piggott remembered, “and were flown for the first time only days before the filming began.” There was a friendly competition among the builders to deliver first. PPS took the prize with its Gipsy Pfalz. On the other hand, Rousseau delivered its D.VIIs by actually flying them from France to the set in Ireland, their German crosses and lozenge camouflage no doubt raising eyebrows below. Behind-the-scenes home movie: aircraft of The Blue Max, Baldonnel, 1965. (Silent) The PPS D.III reportedly flew well, though with heavy controls. On the other hand, the Hampshire Aero Club’s all-wood Pfalz earned the nickname “Rubber Wings” during filming. The steel-tube S.E.5as were strong and maneuverable, said to be easy to fly, but the D.VIIs were reportedly very heavy and—though their Gipsy Queens ran at twice the rpm of the original Mercedes—under-powered. Likewise the Dreideckers, originally famous for their agility, suffered from the lack of rotary engine torque. Garrison reported, “The [Bitz] triplane has the flying characteristics of a Link Trainer.” Searching for a properly European location, since the Flanders fields were now in the most intensely populated, smoggy and air-trafficked part of the continent, the producers settled on Ireland. The aircraft ground scenes were shot at Weston Aerodrome near Dublin. In the film’s final sequence, Casement Aerodrome, to the southeast, stood in for Berlin Tegel. (Tempelhof wasn’t built until 1927). Back in 1928, when it was still named Baldonnell, Casement had been the site of a German aviation milestone, when a single-engine Junkers W 33, the Bremen, departed there on the first successful east-west crossing of the Atlantic. Locations The exteriors for “Berlin” in The Blue Max were shot in and around Parliament Square, Dublin. The tower-like structure at left center is the Campanile bell tower of Trinity College.  The Trinity College chapel served as German headquarters.  Weston Aerodrome, 1965. The grass field is now overlaid with a modern runway and taxi lane. The steeple in the right-distance may be The Wonderful Barn, about a mile away across the River Liffey. Mouse over the aerial view below to pinpoint the film site (all hangars and sets long since demolished), or click for map view.

Casement Aerodrome (now Casement Airbase), about three and half miles southeast of Weston, has also been greatly improved since 1965. Much of what was grass then was already under concrete by 1982. The building in which the dramatic final scenes take place (A) and in which Stachel is detained while Heidemann flies the “Fokker D.VIII” (B) were both movie props, and dismantled when production was complete. The sites are now (A) an enclosure where an aircraft was displayed for a period some years ago and (B) a light pole. The building just above (A) (with vehicles parked behind it) is the present Casement VIP Terminal.

Many thanks to Capt. Seán McCarthy of the Irish Air Corps Press Office, and Casement historians, Airman Michael “Mick” Whelan and Tony Kearns for their help with these photos. The movie production was run as a near-military operation under command of technical advisor Cdr. Allen Wheeler. 1,100 officers and men of the Irish Army, under liaison officer Lt. Col. William O’Kelly, served as extras, switching uniforms as necessary and equipped with 2000 rifles, 24 field guns (75mm and 18-pounder), 20 mortars, 20 armored cars, 500 grenades and a plentitude of machine guns. Recreating the Somme no-mans-land required some 230 acres near Kilpedder, six miles from Ardmore in County Wicklow on Ireland’s eastern coast, upon which an entire semi-destroyed French village was built like a life-size diorama. Top explosives experts Karle Baumgartner of Germany and England’s Ron Ballanger came in to supervise the battle scenes. “We shipped in our own explosives,” said Ballanger, “because we had to have absolute knowledge of its properties. That meant getting special permission of the Irish government which, fortunately, proved most cooperative.” Using five radio sets and 25 miles of wiring, their team of 60 set off over 5,000 separate blasts—about seven tons of explosives per day, some thousand tons all told. Battle scenes from The Blue Max. One of the aircraft appears to be an S.E.5a repainted to play a German Fokker. The machine guns were oxyacetylene torches, intermittently lit by spark plugs activated from the pilot’s stick and burning lean to give a white-hot feather. Smoke was delivered by fireworks canisters, set off by electrically fired detonators, with a burn time of about a minute each and requiring asbestos shielding and flame-resistant paint to avoid setting the aircraft afire.

Filming the scene at 07:30, in which von Klugermann in his D.VII “buzzes” Stachel on his first visit to the aerodrome. Director Guillermin in cap. Film loader John Earnshaw in glasses. See also this even lower pass. The pilots weren’t the only crew members risking their lives. As a Fokker hopped a tree row, leveled off and rushed the camera, film loader John Earnshaw noticed that he was actually looking down on its wheels. He hit the dirt just before one of them ripped the camera motor out of his hand. Camera operator Chic Waterson was struck on the head, but back at work the next day. Director of photography Douglas Slocombe was hospitalized for three weeks with a wrenched back. 20th Century Fox head of European production and Blue Max executive producer Elmo Williams admitted Guillermin was “indifferent to people getting hurt as long as he got realistic action...a hard-working, overly critical man whom the crew disliked.” And the idea of a bridge fly-through followed by a crash wouldn’t go away. “Where and exactly why the crash was to occur was not yet determined,” recalled Piggott, “because so much would depend on the location used.” At Carrigabrick, east of the village of Fermoy in County Cork, a railway viaduct of wrought-iron lattice girders spanned the Blackwater River on stone pillars. Carrigabrick Castle, the five-story stone keep at one end, was tall enough to snag a low-flying aircraft for a climactic crash. Garrison flew a test run, and Piggott was told the bridge “had been flown under by the pilots of the RAF in the 1930s,” but he flew down to judge for himself. Carrigabrick Viaduct

“From the filming point of view this bridge was ideal,” the stunt pilot noted, “since it was high enough to allow plenty of room for vertical error. However, this did mean that there could be no question of pulling up and over the top of the bridge once the run had been started.” To minimize horizontal error, Piggott precisely set pairs of scaffolding stakes in the ground, with one right out in the river (visible in the movie, far out ahead of “Willi von Klugermann’s” first fly-through). “Then if the pilot flew toward the bridge keeping the two poles exactly in line,” he reasoned, “he must pass through without any problem.” Practicing in a Dreidecker at the airfield, though, Piggott found he required several tries to align the poles. “This was worrying,” he said, “since if I did not get through the bridge on the first run, it was immaterial how well I might have done the others.” The camera ship was a French Aérospatiale SA 318C Alouette II helicopter, flown by Gilbert “Gilly” Chomat, with a cameraman filming from a side mount. Beginning with over-water passes through the bridge’s widest span, Piggott flew 15 successive runs. “Gilbert was able to follow behind me and go through with the helicopter filming all the way,” he recalled. “It was interesting to notice that the ‘take’ selected for the film was not one following the aircraft sedately.... In order to make it more exciting the helicopter had been lifted during the run so the triplane appears to duck down under the top of the bridge.” The next day’s schedule, however, targeted the landward span. “I can remember flying over to the location for the first go under the narrow arch and feeling more like Willi than Stachel,” Piggott wrote. “Circling over the bridge and looking down, the narrow arch looked quite impossible….I was very aware of the fact that the little triplane could not climb over the bridge at the last moment. The biggest danger was the possibility of over-correcting and weaving from side to side.” The risk of accidentally performing the scripted crash had everyone on edge. “The film crew had felt the strain of waiting days for this moment,” Piggott recalled; some were “scarcely able to watch the first run.”

Post-crash analysis According to Google Maps, and discounting elevation change for the sake of argument, the top of Carrigabrick Castle is about 400 feet away from the narrow, landward underpass under which “von Klugermann” makes his last flythrough. Assuming that a diving Triplane would be near maximum speed (115mph) and using an online gee-force calculator, it can be seen that von Klugermann would not only have to go out of his way to hit the tower, but banking more than 180° in that distance would require him to pull almost 4½ gees. Furthermore, as Fokker Triplanes were notorious for wing failures, we might assume that his aircraft would have come apart in mid-turn, launching him on a tangent into the riverbank. This no doubt accounts for Stachel, upon returning to base, insisting to Heidemann that “He hit the trees. He hit the trees!”—because an expert like Heidemann would never believe it possible for the Fokker to have hit the tower!“All I had to do,” he knew, “was to settle down quickly on each run and keep those two poles lined up until the bridge had gone by. I made myself oblivious to the huge stone pillars on either side and did not even glance at them.” The Alouette, with a main rotor span 10 feet wider than the Dreidecker’s wings, could not follow. “In many ways I had the easy job,” Piggott said. “All I had to do was fly through the arch, whereas Gilbert flying the helicopter had to both follow me closely and then pull up and over the top of the bridge at the very last moment….By very clever use of the zoom lens...they were able to film the triplane at close quarters and see it go right through the arch.” Local historian Paudie McGrath, then just 14 (later of the 1st Motor Squadron and 3rd Garrison Ordnance Company, IDF), never forgot the “the beautiful sight each day of upwards to nine aircraft flying over the town of Fermoy…towards the viaduct which spans the River Blackwater east of the town…swoop from the sky and make their final approach in preparation for the flight under the viaduct, then turning right and climbing over the castle, followed by the aerial photography crew in the helicopter. That was the first time I had ever seen a helicopter.” Guillermin wasn’t the only stickler for realism. “I was rather afraid that the whole of this episode might be thought to be faked or done with models, and therefore I suggested that we should put a flock of sheep at the foot of the bridge,” Piggott remembered. “On the first few runs the sheep were scared by the noise and moved about very realistically, but they soon became bored with the aircraft and took hardly any notice at all.” Filming also had to pause in mid-flight as a railway truck rolled innocently through the scene, apparently inspecting the track and, as Piggott reported, “happily quite unaware of what was going on.” “That day I really earned my pay,” he wrote, “with fourteen runs through the narrow arch and two more through the large one. I slept very soundly that night!”

Derek Piggott flies a Bitz Triplane under Carrigabrick Viaduct, east of Fermoy in County Cork, Ireland. Built in 1872 (and closed in March of 1967), the railway was still in operation at the time of production. Both viaduct and castle still stand to this day; the former is being considered as a pedestrian walkway and viewing platform. Note sheep under the flight path.Irish weather prevented flying the third day. Instead the crew mounted a small camera on one of the triplanes to get over-the-shoulder footage. The next day Piggott made two runs wearing Stachel’s helmet, then landed to switch film magazines and don Willi’s helmet. The pass that “kills” Klugermann in the film threatened to kill Piggott. “These last two runs were distinctly exciting,” he understated. “The triplane was buffeted about and I had to bring it back to the center line several times when it had been shifted bodily by the gusts together with the cross wind. This time it was quite a pleasant relief...to know that these were the last runs.” Though somewhat panned for its bedroom scenes (shockingly for a mainstream movie in 1966, Andress semi-exposes a nipple, though in the pre-ratings era the film still received MPAA approval and was released uncut), The Blue Max—one of the last official CinemaScope releases—was universally praised for its aerial action and Jerry Goldsmith score, and won a British Film Academy Award for Best Color Art Direction. TV Guide said it “impressively captures the reality of war in the trenches and in the air.” Roger Ebert, before he was a critic of repute (or evidently much of an aircraft expert), wrote, “they kept shooting the same Messerschmitt out of the sky from different camera angles, but so what? It was a good war movie.” And Monthly Film Bulletin said, “The reconstructed SE-5s, Pfalz DIIIs and Fokker D-VIIs [sic] look as though they were worth the quarter-million dollars spent on them.” Where are they now?The ill-fated SE.5 replicas built by Miles Marine and Structural Plastics Ltd, G-ATGV and G-ATGW, were both written off within a month of each other in 1970.  On August 18, 1970, while filming Zeppelin over the Irish Sea, SE.5 G-ATGW (shown here under construction at Shoreham) rammed the Aérospatiale Alouette II camera helicopter, the same one used to film The Blue Max. Both aircraft were destroyed and all crew members killed.  On September 15, 1970, while performing a low-level maneuver during the filming of von Richthofen and Brown at Weston, Charles Boddington struck the ground in SE.5 G-ATGV and was killed. Aircraft written off.

Four additional SE-5s (N908AC, N909AC, N910AC & N912AC) built after The Blue Max for Darling Lili and used in You Can’t Win Them All, Von Richthofen and Brown and Zeppelin were technically Slingsby T56s, 7/8-scale replicas built on converted Currie Wot biplane kits. They were all sold to The Fighting Air Command in Denton, Texas, in the early 1980s, by which time none of them were airworthy.

The Caudron C.276 Luciole, which played reconnaissance planes for both sides, was crushed in a hangar collapse Some sources state the Caudron was a C.277, or there were two Caudrons, a C.275 (destroyed) and C.272 (went to France). The Fighting Air Command only took delivery of one, serial number 7546/135, N907AC, former EI-ARF, after the hangar accident.  ...and in German colors. Both exhibit same false cowling, but there seems to be a difference at the tail wheel. Different aircraft? Photo: Sgt. Technician Paddy O’Meara

Stampes & Tiger Moths

The Stampe SV-4 and De Havilland DH.82 Tiger Moth are very similar, and as all served as “filler” in The Blue Max, sources are confused on how many of each took part in the production. Above, left to right, are three DH.82s, one SV-4C and the two Miles SE.5s. Some sources list three Stampes (F-BBIT, F-BNMC/G-ATIR, F-BAUR) and one Tiger Moth (G-ANDM). What seems certain is that Stampe N901AC (ex-F-BAUR) was the one that came to the US as part of the sale of the fleet to the “Fighting Air Command” in Denton, Texas, in the early 1980s.  Three De Havilland Tiger Moths and a Stampe SV-4 wearing German lozenge camouflage in The Blue Max. Tiger Moths all now wearing normal cowlings. 1948 Stampe SV-4C, serial number 1060, N901AC, former EI-AVU and F-BAUR. Flew in Texas in the 1980s. Was also used in the movie Pancho Barnes starring Valerie Bertinelli, where she was flown through the open doors of a large hangar. Now based in Bermudian Valley Airpark, East Berlin, PA. Many thanks to current owner Pat Fischer for help with its history. Photos © Jason Harry and Zane Adams, used by permission.

Pfalz D.III

The two Pfalz D.III fighters flown in the The Blue Max were built separately, but have stayed together through their careers. Both appeared in Darling Lili, and were later part of the sale to the Fighting Air Command in the 1980s. Both now reside with The Vintage Aviator Ltd., in New Zealand. Pfalz D.III G-ATIJ, built by Hampshire Aeroplane Club, Ltd., serial number PT16, N905AC, former EI-ARD. Formerly on public display, currently in storage at Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre, New Zealand. Pfalz D.III N906AC, built by Personal Plane Services Ltd., serial number PPS/PFLZ/1, former EI-ARC. Flew as part of the Fighting Air Command in colors of Werner Voss. Currently flying at Omaka Aviation Heritage Centre, New Zealand, in the colors of Lieutenant Fritz Höhn of Jasta 21, who ended the war with 21 victories.

Fokker D.VII-65s

The three Fokker D.VII-65 replicas built by Rousseau Aviation of Dinard, France, for The Blue Max, recognizable by prop spinners at the top of the nose rather than the bottom, as on originals, and by carrying underwing bombs. LIke most of the fleet, they also served in Darling Lili, then fell into disrepair. Their subsquent whereabouts are better documented than most of the rest of the movie fleet. In the ’80s all three briefly resided with The Fighting Air Command in Denton, Tex.

The first Rousseau D.VII-65, #N902AC, which in Texas flew in the colors of German ace Rudolf Berthold, now flies in New Zealand as ZK-FOD with The Vintage Aviator Ltd. Has been restored to more accurately resemble an original D.VII.

The second D.VII, #N903AC, is currently at the Stampe & Vertongen Museum at Antwerp International Airport, Belgium. A landing accident rendered it un-airworthy, but it is being gradually restored. Still has its Gipsy Queen engine.

The third Blue Max Fokker D.VII, #N904AC, on display at the Southern Museum of Flight in Birmingham, Alabama, includes a mockup of the original Mercedes engine.

Bitz Triplanes

The Fokker DR.1 triplanes built by Bitz Flugzeugbau GmbH of Augsburg, West Germany, for The Blue Max. Not part of the sale to the Fighting Air Command, they have had wildly different subsequent histories.

It’s the red Fokker Triplane that’s had the most dramatic life story. In October 1978 it vanished from Garrison’s Ireland hangar. Police turned up no leads. Three years later, leafing through an issue of Air Progress magazine, Garrison recognized it in an ad, about to be auctioned off on behalf of a defunct Orlando air museum. He showed up with a sheriff, took possession, and had it trucked to a hangar in Chino, CA. While awaiting full restoration, it was stolen again. Changing hands repeatedly, slowly going to pieces, the Dreidecker was rediscovered in a Southern California backyard, covered in weeds. The find was announced in 2008 on the Internet, where Garrison had long searched for any trace. His son Patrick fetched it home to Pearson Field, Washington, where restoration is underway today. “All of the original parts for the Blue Max Triplane have been located,” Garrison reports, “with the original rudder being located in a collection in Texas, and the original twin Spandau movie guns that have been located in a collection in the Pacific Northwest.” It’s just a matter of time and money before the Dreidecker flies again. To get the full story, or donate, visit blue-max-triplane.org.  Bitz Triplane F-AZPQ. Now owned and flown by “Les Casques de Cuir” (“The Association of Leather Helmets”), in the colors of Manfred von Richthofen. Photo © Jeroen Stroes, used by permission. The twice-stolen Bitz Triplane N403BM. Finally recovered by the Garrison family and undergoing restoration. Photo © Blue-Max-Triplane, used by permission.

1931 Morane-Saulnier MS.230

Morane-Saulnier MS.230 F-BGMR stood in for a Fokker D.VIII monoplane in The Blue Max. Among the last to appear in the film, the Morane’s scenes were actually some of the first shot, to establish the feasibility of stunt pilots working with the helicopter camera ship. Derek Piggott recalled, “We went up one evening when there were towering cumulus clouds rising to about ten thousand feet. The evening light gave a slightly golden tinge to some of the clouds, and the billowing white turrets contrasted against the deep blue above and the almost mauve shadows below.... The aim was to shoot some long lengths of uninterrupted manoeuvres keeping as close as possible [to the helicopter] and literally tossing the aircraft from one attitude to another to keep the action fast.... I was completely uninhibited! We finished with a long, long spin of thirteen or fourteen turns down into a valley, between the towering clouds. It was an exhilarating experience.... I knew that it had gone well and that there had been magic that evening.” As F-BGMR, the Morane later flew as the camera ship in filming Darling Lili. The German crosses are still faintly visible on its upper wings. Photo © R.A.Scholefield, used by permission. By the early 1980s the Morane, re-registered as EI-ARG and then G-BJCL, had been repainted in French colors and was flying out of Wycombe Air Park (Booker Airfield). Photo © Baldur Sveinsson, used by permission. Visit his site. Since 1989 the Blue Max Morane-Saulnier MS.230, re-registered as N230MS, resides at the Fantasy of Flight Museum in Polk City, FLA.To Hunter’s probable chagrin (he passed away in 2009), most fans of the movie have never actually read the novel, which even he admitted is full of character ruminations that don’t translate well to the screen. The Bruno Stachel they know is as Peppard portrayed him: a survivor of the trenches, more worldly upon stage-entrance than his literal counterpart but more oblivious upon exit, dreaming he’s achieved everything he's ever wanted even as his superiors plot his (ig)noble end. “He got killed at story’s end,” Hunter groused, “to satisfy Hollywood’s lingering Victorianism, which required bad guys to die or otherwise get the shaft.” (In the novel Stachel not only survives but goes on to two sequels.) All right, nits can be picked. Planes go down smoking profusely from nothing more flammable than wheel struts. Spandaus fire without ammo feeds. German pilots wear Uhlan uniforms and WWII-era goggles. Their late-war Fokkers carry underwing bombs, and bear the early-war cross pattée instead of the 1918-correct Greek cross. (When Hunter challenged Art Director Fred Carter on that, he was told simply, “That kind of cross photographs better.”)

Peppard and Hunter at the New York premier of The Blue Max, 1966

Derek Piggott (left) with former Sgt. Technician (“and a good one!” say his mates) Paddy O’Meara, Irish Air Corps, at the September 2008 reunion of pilots, technicians and film production personnel who helped make, among others, The Blue Max, Darling Lili, Zeppelin, and The Red Baron, all in Ireland. Photo: Tony Kearns, used by permission.And the bridge scene strains credulity. Any pilot flying under the Carrigabrick viaduct would have to pull a neck-breaking 180° bank across the river to “accidentally” hit the castle—though to its credit, a Fokker Dreidecker is one of the few aircraft ever built that might actually pull that off. But the fact remains, the crew of The Blue Max not only built their own air forces, they flew them against each other in air-combat maneuvers, and earned $5 million at the box office doing it, worth nearly $37 million today. Director and aviation enthusiast Peter Jackson (The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit) calls it one of his favorite World War I movies of all time, and the very best when it comes to the air war. How can any movie buff—or aviation buff—think otherwise? CGI artistry simply can’t compete with actual pilots wagering their lives, flying for-real wood-and-wire aircraft just they flew them at the dawn of aviation. As those ages of both filmmaking and air warfare draw now swiftly to a close, such scenes are not ever likely to be captured so well again.

About the authorAuthor/illustrator/historian Don Hollway has been published in Aviation History, Excellence, History Magazine, Military Heritage, Military History, Civil War Quarterly, Muzzleloader, Porsche Panorama, Renaissance Magazine, Scientific American, Vietnam, Wild West, and World War II magazines. His work is also available in paperback, hardcover and across the internet, a number of which rank extremely high in global search rankings. More from Don Hollway:

|