Six British battleships, three battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, 16 cruisers, 33 destroyers and eight submarines, against one German battleship. It was an even match.

|

A battleship on the move, bristling with big guns and deadly intent, gets everyone's attention. In late May 1941 a warship of neutral Sweden sighted a German battleship and heavy cruiser transiting the Danish Straits from the Baltic Sea into the North Atlantic. The news flashed immediately through diplomatic and espionage channels to London: the world's most powerful battleship, Germany’s KMS Bismarck, was putting to sea. For Great Britain, that spring was the low point of the war. Germany had conquered Poland, France, Denmark, Norway, and Greece. German bombers were pounding London and other English cities. General Erwin Rommel, the “Desert Fox,” had driven British forces across the Sahara and was threatening to take Egypt. On May 20 German paratroopers began their takeover of Crete. The next day, the Bismarck was unleashed on the North Atlantic, where England had 11 convoys, including troop transports with 20,000 men, at sea or due to sail. If the raider got in among them she might very well win the war at a stroke.

The Construction Office of the German Navy began preliminary and contract design work on Battleship “F” (Bismarck) in 1934, According to the 1935 Anglo-German Naval Treaty, Germany was permitted to build a 35,000 long ton battleship armed with 14” (35.6 cm) main guns. As a result of the 1936 Second London Naval Treaty, the allowance was enlarged to 45,000 long tons and 16” (40.6 cm) guns. Therefore, it was legal for Germany to construct battleships with a standard displacement of 45,000 long tons by 1940-1941, as was the case for the Bismarck. The fact that Bismarck displaced 50,000 tons was kept secret.) The launch ceremony, at 1300 on Tuesday 14 February 1939, was attended by more than 60,000 people. Hitler formally named the vessel in honour of Germany’s founder and greatest statesman, Otto von Bismarck. Dorothee von Löwenfeld-Bismarck, daughter of Wilhelm Otto Albrecht von Bismarck-Schönhausen, Otto von Bismarck’s second son, performed the christening: “On the order of the Führer, I christen you with the name Bismarck.” The hull was stuck fast on the slipway for three minutes before it was finally freed and slid into the water. Enlarge

KMS Bismarck As she appeared in the Baltic Sea, just before her breakout into the Atlantic, camouflaged with false bow and stern waves to give a misleading impression of her length. Built in complete Nazi disregard for interwar treaties limiting battleship size, Bismarck displaced approximately 50,000 tons, making her the largest then afloat. Compared to the pride of the Royal Navy, the 1920s-era battlecruiser HMS Hood, Bismarck boasted comparable firepower—eight 15-inch main guns—with better armor, speed and range. (Bismarck’s captain, Ernst Lindemann, always referred the battleship as a “he.”) Moreover, on her maiden voyage Bismarck would be accompanied by the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. Fleet commander Admiral Günther Lütjens was an experienced Atlantic raider. From January to March he had taken the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on a two-month, 18,000-mile rampage, destroying or capturing 22 Allied vessels. What he might accomplish with Bismarck and Prinz Eugen struck terror into British hearts. Once out on the open sea, where might Lütjens strike first? Operation Berlin

KMS Gneisenau

KMS Scharnhorst Precursor to Operation Rheinübung was Operation Berlin in January–March 1941. During both World Wars, Germany’s naval objective against Britain was to cut her economic lifeline: the huge numbers of merchant convoys bringing in food and supplies from the United States. To do this, Germany’s naval commander Grand Admiral Erich Johann Albert Raeder’s desire was to blockade Britain with surface commerce raiders—cruisers, battle-cruisers, fast battleships—supported by submarines. Operation Rheinübung (“Exercise Rhine”)

KMS Prinz Eugen In May 1941, the original plan was to have both Scharnhorst and Gneisenau sail with Bismarck and Prinz Eugen. The former battleships were both at Brest, on the western coast of France, where they had been heavily bombed by the Royal Air Force. Scharnhorst was undergoing repairs to her engines, and Gneisenau had taken a torpedo hit which put her out of action for six months. None of Germany‘s three light cruisers had the endurance necessary for a lengthy Atlantic raid, and the crew of Bismarck’s newly completed sister ship, Tirpitz, was not yet fully trained. Raeder ordered Rheinübung to go ahead over Lütjens's protests. Captains Lindemann and Brinkmann were both graduates of the German naval academy class of 1913. Lindemann had never held any shipboard command, but he was Germany's leading naval gunnery expert and considered an outstanding leader. He believed Bismarck too powerful to be referred to as a female and always referred to the battleship as “he” rather than “she”. Thick cloud cover made it impossible to spot the German warships from the air, but from the Norwegian coast there are only four outlets into the mid-Atlantic: between the Orkney Islands and the Shetlands, the Shetlands and Faroes, the Faroes and Iceland, or the Denmark Strait, between Iceland and Greenland. To block them, Commander-in-Chief of the British Home Fleet Admiral Sir John Tovey dispatched the Hood and the battleship Prince of Wales, so new it still had civilian workmen aboard, to Iceland. Tovey himself sailed from the Royal Navy’s home base at Scapa Flow in the battleship King George V with the battlecruiser Repulse, aircraft carrier Victorious, four cruisers and seven destroyers, to cover the nearer routes. In May the Denmark Strait, 180 miles across, is half-closed with pack ice. Much of the rest was sown with British mines, leaving a passage at most 40 miles wide. On the evening of Friday, May 23, the cruisers Suffolk and Norfolk, patrolling the narrows, suddenly found the German warships barreling out of the mist, straight at them. Bismarck opened fire on Norfolk from just six miles, practically point-blank. One shell bounced off the water and ricocheted off the cruiser’s bridge, but the rest fell short or passed over. Both British ships escaped into the fog. Lütjens let them go. He was after bigger game. Following at a safe distance, the cruisers broadcast the news: Bismarck had been found. The Battle of the Denmark Strait

Cruiser HMS Norfolk

Cruiser HMS Suffolk

Battlecruiser HMS Hood

Battleship HMS Prince of Wales

Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland

Captain Ralph Kerr

Captain John Leach

The Battle of the Denmark Strait (German). 300 miles to the south, Vice-Admiral Lancelot Holland on the Hood immediately led the Prince of Wales on an intercept course. At 5:35 AM Saturday morning, Prince of Wales sighted the Germans 17 miles off their starboard bow. To narrow the distance required Holland to turn nearly bow-on to the enemy ships, allowing them to “cross his T”: bring full broadsides to bear while he could reply only with bow forward guns. It would cut his gunnery advantage from 18 guns cannon to just ten, against the Germans’ 16. But Holland wasn’t the kind of man to shrink from battle merely because his position wasn’t to his liking. He ordered a turn to starboard, and at 5:53AM, from 25,000 yards, Hood let loose the first salvo at the lead enemy ship. Unfortunately for Holland, that ship was not Bismarck, but Prinz Eugen. Unknown to the British, in the previous evening’s encounter with Norfolk, the concussion of the battleship’s own first salvo had knocked out her forward-looking radar. Lütjens had ordered Prinz Eugen into the lead to feel the way forward through the dark. Even at dockside the cruiser, often called “Bismarck’s Little Brother,” looked like a 4/5 scale model of the battleship. At sea, from a distance, the two ships’ silhouettes were nearly identical. Artist: Manuel P. González López Aboard Prince of Wales, however, there was no mistake. As Hood’s shells fell just astern of Prinz Eugen, the Prince targeted Bismarck with its first barrage. It missed. And one of its brand-new guns went out of action, reducing the British advantage still further. (Neither Norfolk nor Suffolk played much role in the fight.) Meanwhile the Germans steadily walked their shells onto Hood. At almost exactly 6:01AM Bismarck’s fifth salvo arched across 15,500 yards to punch deep into the battlecruiser’s bowels. A terrific gout of flame shot skyward from behind the Hood’s aft funnel, an immense cloud of black smoke enveloped the ship, and observers on the nearby vessels were shocked and horrified to see her bow suddenly loom into view, standing nearly vertically in the water. The pride of the Royal Navy had exploded and broken in half. At about 6:00AM Holland ordered the British ships to turn once again to port to bring their aft main guns to bear. As they turned, a shell from Bismarck struck just behind Hood's mainmast and penetrated her aft ammunition magazines. At almost exactly 6:01AM, Hood exploded, broke in half, and sank in about three minutes. So sudden was the end only three of Hood’s crew escaped. Admiral Holland and 1416 men went down with the ship. Bismarck and Prinz Eugen now concentrated their fire on Prince of Wales, delivering seven heavy hits in quick succession, including one to the bridge that killed everyone there except the captain and two others. With only one gun still functioning, the British battleship withdrew under a smoke screen. The battle lasted just 17 minutes. At 5:53AM Hood opened fire at approximately 26,500 yards, aiming at the lead German ship, Prinz Eugen, assuming she was Bismarck. Prince of Wales engaged and hit Bismarck. The Germans held fire until 05:55, then both targeted Hood. (A) Bismarck opens fire. (B) About 6:02AM. The Germans weave back again. Bismarck, guns pointed almost dead away, has just fired a full broadside. (C) About 6:09AM. Bismarck crosses Prinz Eugen’s wake and fires a last salvo, from the aft turrets. Brightness of fireballs darkens the image. (D) After the battle Bismarck, hit three times, down at the bow. All shots taken from Prinz Eugen.

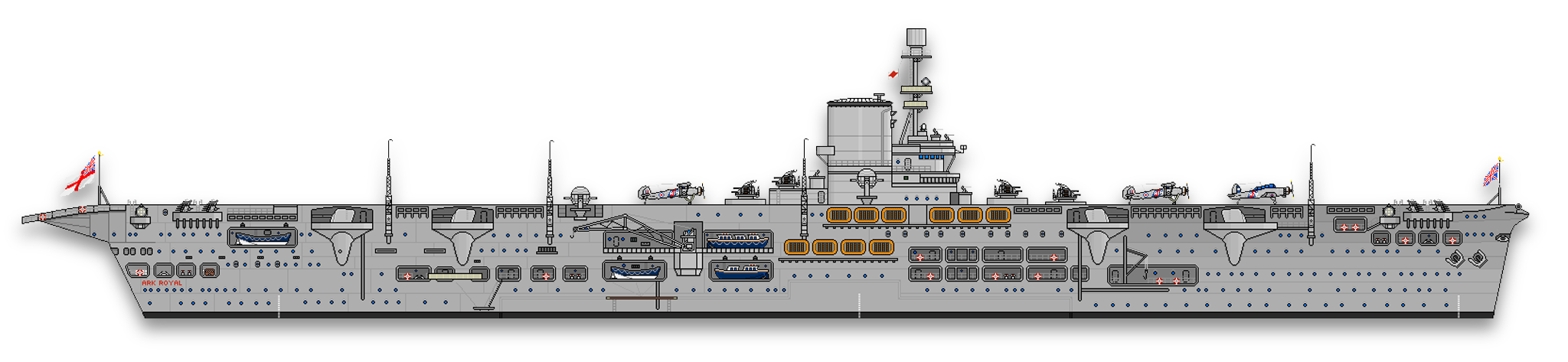

See also this YouTube version with added sound effects. Lütjens did not pursue. Prince of Wales’ guns had shot well enough to put a shell through Bismarck’s bow. Seawater had fouled her forward oil tanks—1000 tons of precious fuel wasted. Bismarck had gone noticeably bow-down and was trailing a slick. Convoy-hunting was out of the question. Lütjens had to make for St. Nazaire in occupied France for repairs. He authorized Prinz Eugen, unscathed in the action, to carry on, and at 6PM turned on their pursuers, trading a few shots with Suffolk and Prince of Wales while, unnoticed, the cruiser slipped away. (Prinz Eugen would be one of the few major German naval vessels to survive the war. She withstood two atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll in 1946, but developed a slow leak and capsized at Kwajalein that December.) The loss of the Hood was a gut punch not only to the Royal Navy, but to the entire British Empire. Admiral Tovey’s task force was still hundreds of miles to the southeast. He plotted a new course to intercept Bismarck further south, and called in reinforcements. Vice-Admiral Sir James Somerville sailed from Gibraltar with the battlecruiser Renown, aircraft carrier Ark Royal, cruiser Sheffield, and six destroyers. In mid-ocean the old battleship Rodney was released from escort duty. In all, it was the largest combined naval fleet of the war to date: six battleships, three battlecruisers, two aircraft carriers, 16 cruisers, 33 destroyers and eight submarines, against one German battleship.

Forces involved in Operation Rheinübung. Germans at top, most others British Still, it was a big ocean. Bismarck might speed through the trap and reach safe harbor, or British convoys, before the fleet intercepted her. To slow Lütjens, Tovey ordered Victorious to launch an air attack. The carrier’s antiquated Swordfish torpedo bombers were some of the last combat biplanes still flying (their crews nicknamed them “Stringbags”), they would not be in range until dusk, and would have return and land in darkness. It was a risk that had to be taken.

Fairey Swordfish Mk.I

The first ship they sighted, and nearly attacked, was the Norfolk. Radar showed another ship ahead, but when the Swordfish prepared to attack, the pilots saw it wasn’t the Bismarck either. It was the US Coast Guard cutter Modoc, on neutrality patrol, which had blundered into the battle zone. (Both Norfolk and Prince of Wales made the same mistake misidentification, but before they brought their guns to bear, the Modoc escaped.) In the long sub-arctic day, the Swordfish finally located Bismarck. Skimming in low over the waves through bursts of anti-aircraft fire, they only managed to score one hit, on the torpedo-proof armor belt around the battleship’s waterline. At least all the aircrews managed to return to Victorious. That was the only good news for Tovey. Wily Lütjens had noticed the Royal Navy ships chasing him were all zigzagging to dodge any lurking submarines U-boats. At 3:00 AM Sunday morning the British zigged, and Bismarck zagged. When they turned back again, the battleship was gone. To broaden the search, Tovey scattered his fleet. He sent Suffolk and Norfolk west and Repulse southwest, on the assumption that Lütjens was still headed for the mid-Atlantic hunting grounds. By the time the British got a fix on Bismarck again—unaware he had given his pursuers the slip, Lütjens did not maintain radio silence—the damage had been done. Suffolk and Repulse were so far to the west that they were out of the fight. Prince of Wales and Victorious, almost out of fuel, had to turn back for Iceland. Old Rodney’s position was uncertain; her captain was staying off the air. Somerville’s force, still a thousand miles southeast, was laboring through a heavy gale, with Ark Royal unable to launch search planes because her flight deck—63 feet above the waterline—was pitching 55 feet, half-awash. Alone on the chase, King George V was no match for Bismarck, which in any case was already a hundred miles ahead and pulling away. Finally realizing he had shaken his hunters, Lütjens went silent. Bismarck vanished. In another 24 hours it would arrive under cover of German U-boats and warplanes out of France. Berlin would declare a great victory. British morale would suffer. America would have yet another reason to stay out of the war. Throughout the rain-swept night, the only thing flying was a pair of American-built, long-range Catalina flying boats of RAF Coastal Command in Ireland. Monday morning, just 500 feet above the waves, one of the crews spotted a battleship plowing along all alone. It responded with a blistering volley of flak. Hit and hit again, the Catalina escaped back into the clouds, her wireless operator madly transmitting Bismarck’s position to all listeners. No sooner had the Catalina disappeared than a scout plane from Ark Royal arrived to shadow Bismarck. By 6PM Sheffield, having raced ahead of the task force, was positioned to maintain contact and direct the air strike.

Launch Against the Bismarck, by Robert Taylor In contrast to Victorious’ Swordfish crews, Ark Royal’s were some of the Royal Navy’s most experienced. One by one the spindly biplanes trundled off the wildly pitching flight deck and disappeared into the mist. Their crews soon spotted a lone warship ahead. No flak came up to greet them; the Swordfish dropped down and released their torpedoes. Many, fitted with newfangled magnetic fuzes, exploded upon hitting the water. The ship eluded the rest. Only then did the Swordfish crews realize they’d attacked Sheffield. Aboard Renown, Somerville furiously decreed another air strike to be carried out before nightfall—the last chance for the British to stop Bismarck. Guided this time by Sheffield, the Swordfish pressed home their attack. As the German ship dodged, weaved, and used its big guns to send up shell splashes in their paths, their torpedoes, refitted with reliable contact fuzes, scored two hits, but against the battleship’s armor belt. The last flight, however, delivered a hit on its stern.

Avenging The Hood: Bismarck, And Swordfish Of 818 Squadron RN by Ron Cole. Buy the print. Just as British hearts sank with the belief that Bismarck had escaped, Sheffield reported that the German battleship had come about 180 degrees. When confirmation came from Ark Royal’s scout planes, Tovey realized it was true. His quarry was headed right for him. The last torpedo hit had jammed Bismarck’s rudders in mid-maneuver, a seemingly minor but ultimately fatal blow. Unable to steer, the big battleship could only wander aimlessly while her killers closed in. Lütjens radioed Berlin: “Ship unmaneuverable. We will fight to the last shell. Long live the Führer.”

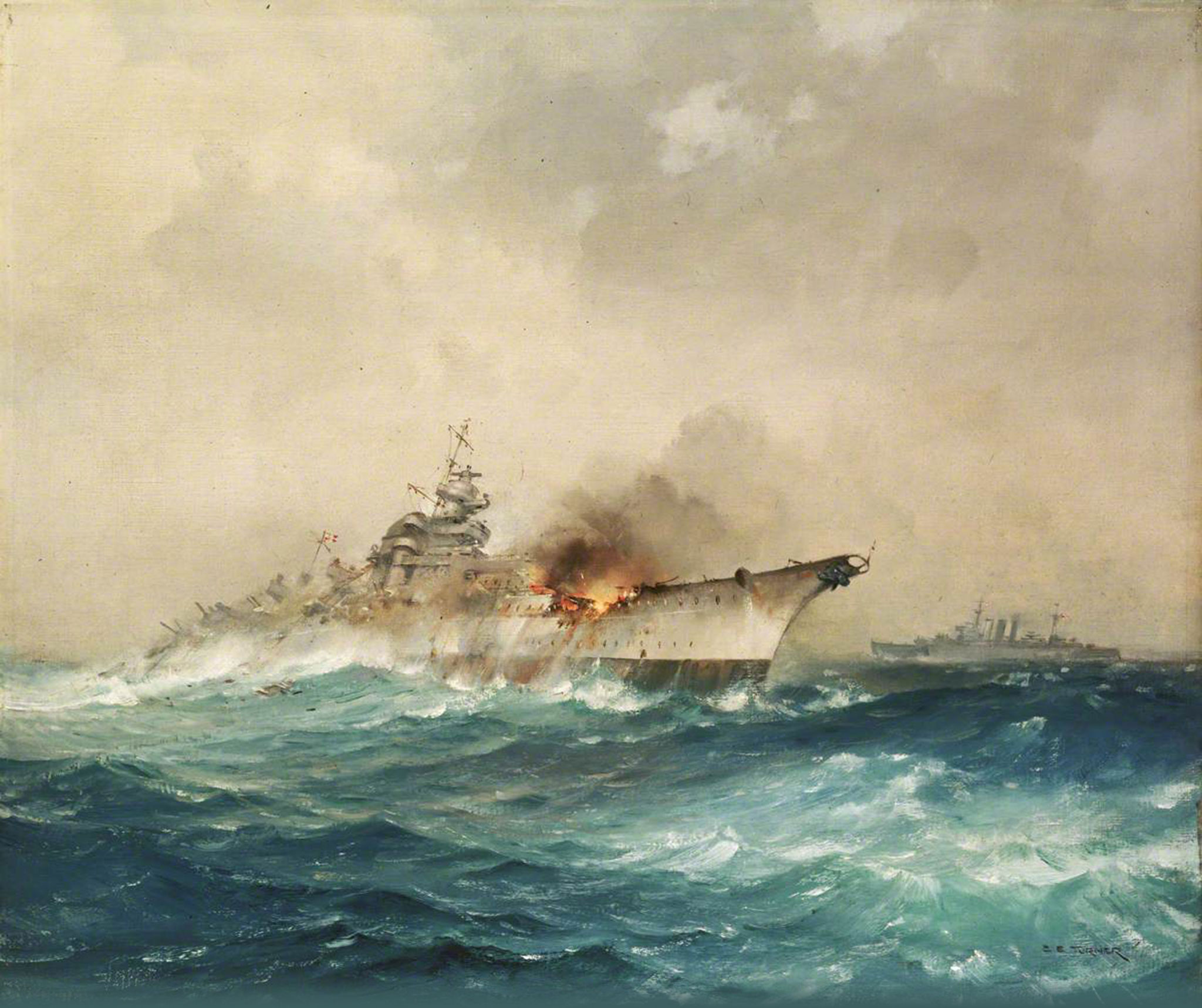

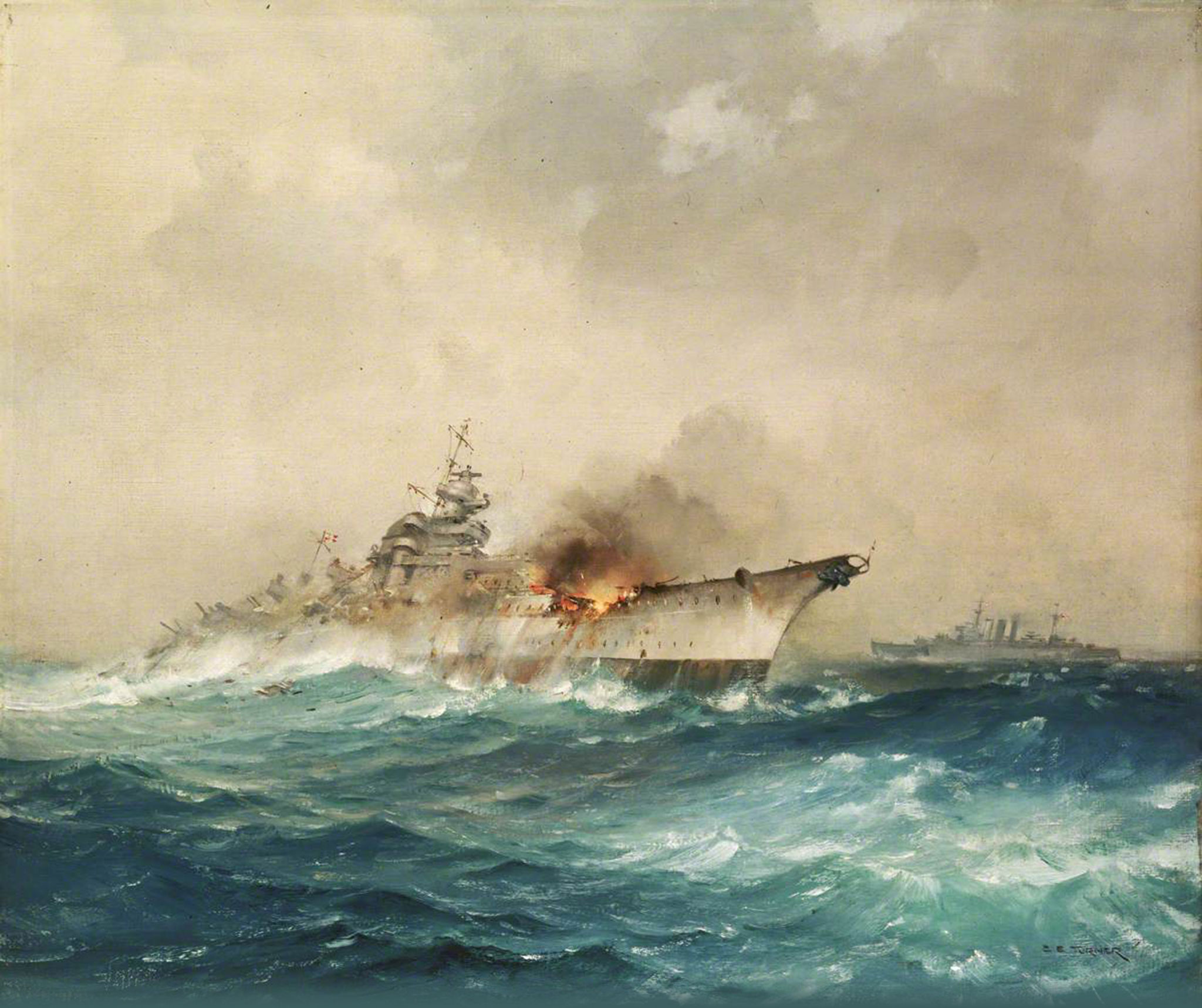

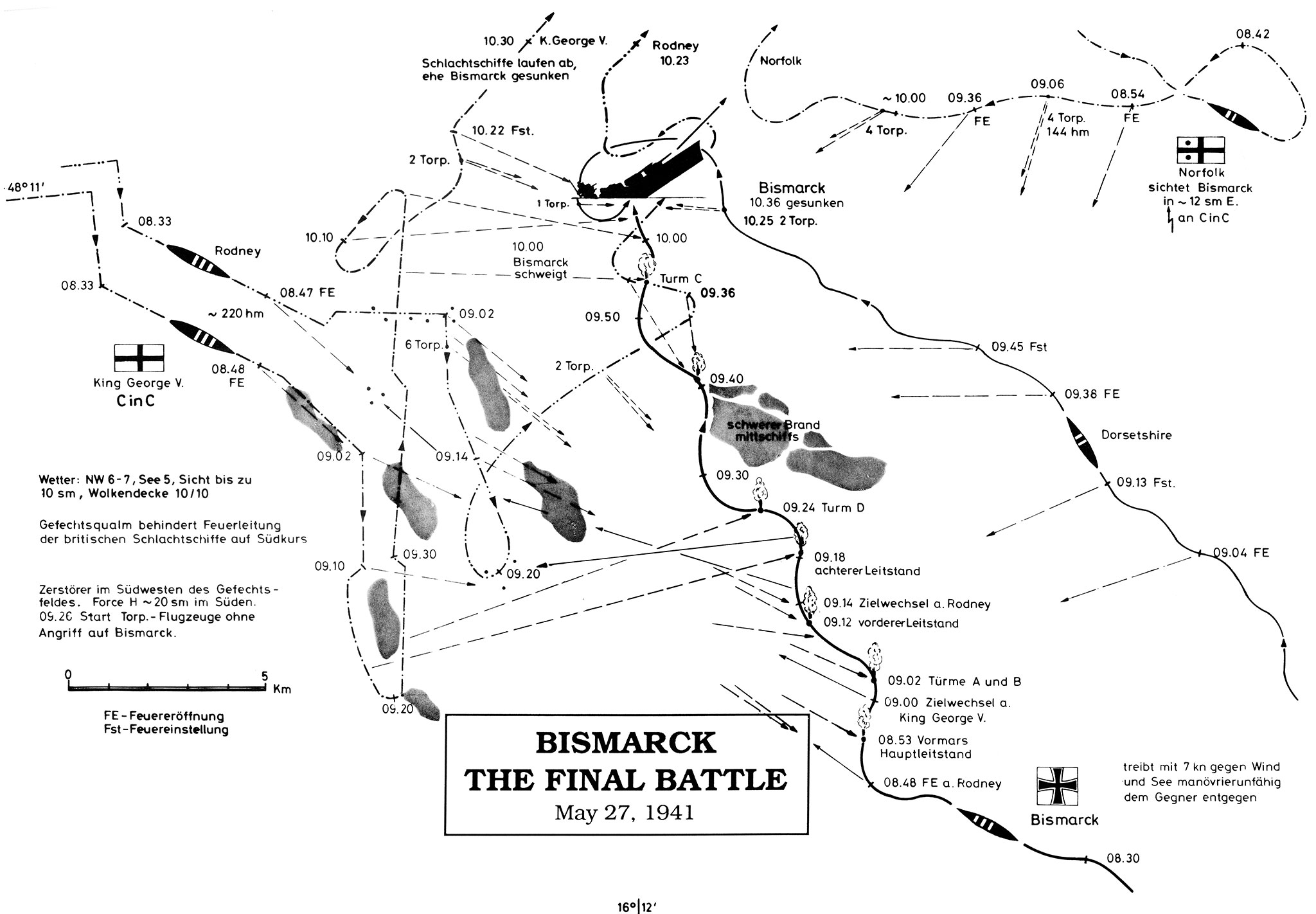

First to arrive were five destroyers that had abandoned convoy duty in order to bring Bismarck to bay. Through the stormy night they harried her with torpedo attacks. Come Tuesday morning, Norfolk had her in sight. King George V and Rodney approached from the west, with night behind them. While they kept Bismarck occupied, Norfolk and the heavy cruiser Dorsetshire, racing up from convoy duty to the southwest, would sneak in to attack from the other side. With the main event about to commence, it had to be on Tovey’s mind that Bismarck had already won a fight against two capital ships and two cruisers. Against all those broadsides, however, she was outmatched. At 8:47AM, Rodney let fly her first salvo of 16-inchers from 23,400 yards. Within a minute King George V joined in. Bismarck replied handily, but nothing could long withstand the hammering of so many big guns. Lütjens was probably killed when one of King George V’s 14-inch shells riddled his bridge with shrapnel. Within 15 minutes Bismarck’s two forward turrets were out of action, and by 9:30 the aft turrets as well. Götterdämmerung at Sea

HMS Rodney (right) firing on Bismarck, burning in the distance

HMS Rodney

HMS Ark Royal

HMS King George V

HMS Dorsetshire

HMS Ark Royal As she appeared in 1939

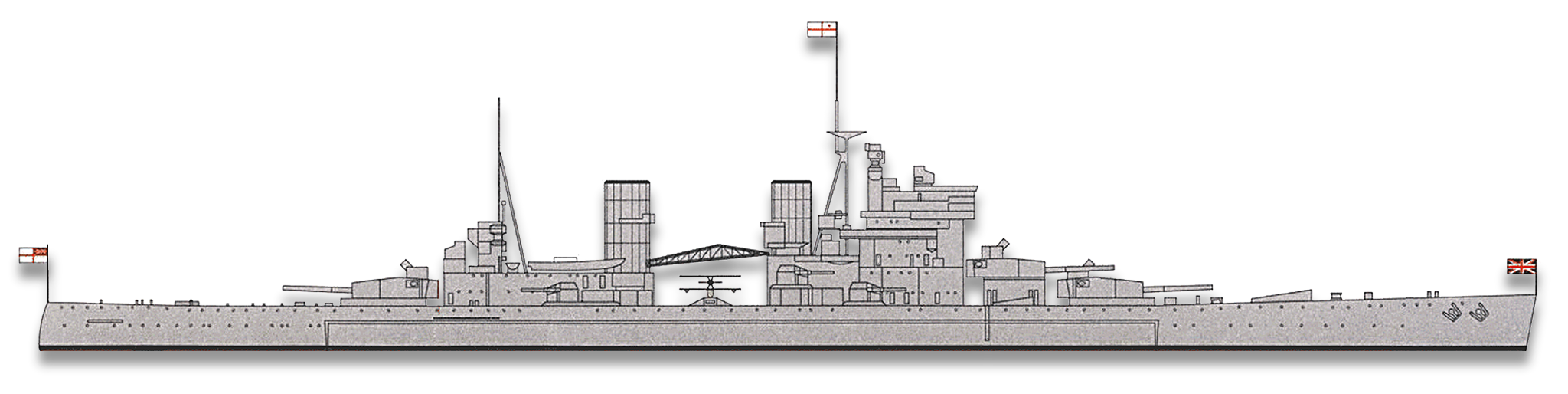

HMS King George V As she appeared in 1941

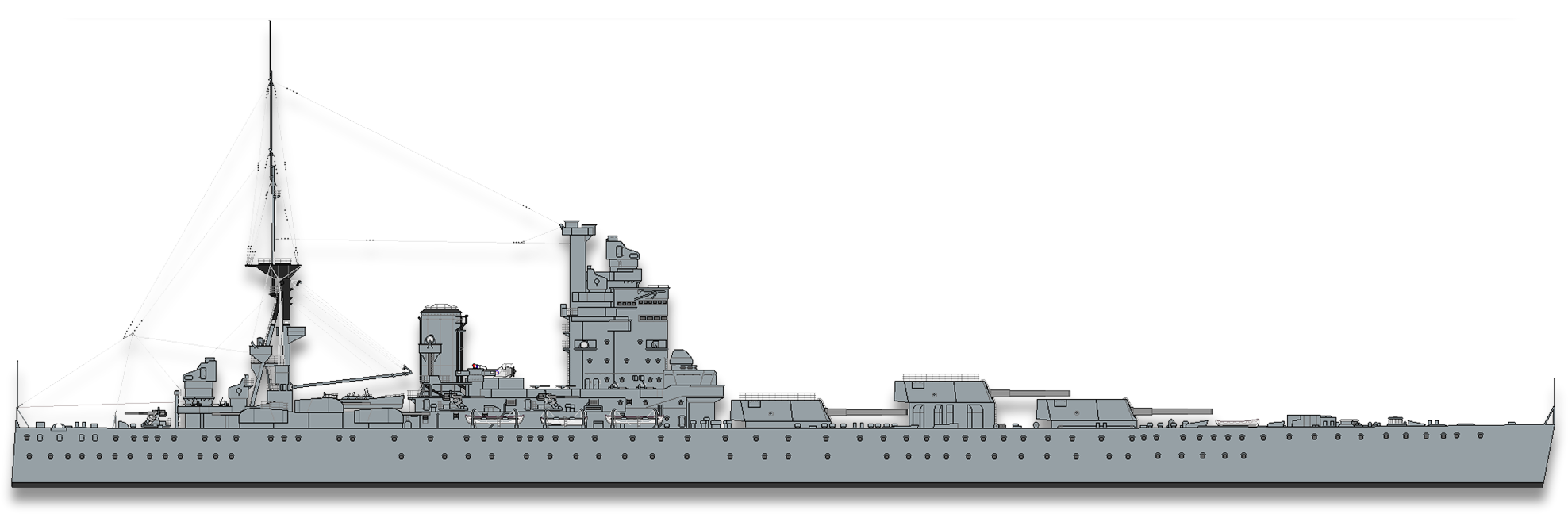

HMS Rodney As she appeared in 1941

The Bismarck’s final battle (German). After that it was mere gunnery exercise; Rodney and King George V fired over 700 large-caliber shells (Rodney alone claimed 40 hits) and Norfolk and Dorsetshire nearly 800 8-inch rounds. But because of the short range most of the shells, fired at flat angles, did not penetrate down inside Bismarck. Burning, her upper works smashed, guns pointing at crazy angles, she would not go down. Tovey could stay no longer. King George V, Rodney and Norfolk were all nearly out of fuel, and each minute increased the threat of U-boat or air attack. Turning away, he signaled Dorsetshire to administer the coup de grace with torpedoes, but it seems Bismarck’s crew scuttled it first. The battleship settled slowly by the stern, and at 10:36 AM rolled over and sank. Captain Lindemann is said to have gone down saluting. Only 115 of his 2200 crewmen survived. The pursuit of the Bismarck was one of the last great battleship duels in history. The success of the flimsy Stringbags against her presaged the ascendancy of aircraft as the supreme naval weapon. (In December 1941, three days after carrier-based planes ravaged American battleships at Pearl Harbor, Prince of Wales and Repulse were both sunk by Japanese land-based bombers off Singapore.) Great Britain breathed a sigh of relief at Bismarck’s destruction, but no seaman worth his salt loves to see a ship sunk. As Tovey put it, “The Bismarck put up a most gallant fight against impossible odds, worthy of the old days of the Imperial German Navy, and she went down with her flag flying.”

More from Don Hollway:

|